–and they belong to the realms of our boldest expressions

RECENTLY, I was hanging out with my youngest, and since my music system is not functioning, her phone is where I coax her to provide me with that memory when a song comes to mind. With me, songs archive memories that may become relevant even when writing an article or the script for a drama, towards recording events from a specific period.

Music influences souls differently. On this occasion, I made the rude mistake of telling my child that her age group is from a period of human history with a low presence of moving love songs and significant philosophy. Out went my ‘Manhattans’, as the quest to prove the old man wrong began.

The search on her phone generated love songs, but I prevailed in the compromise of agreement. A term that I had never used before, ‘Intertextuality’, was introduced and demonstrated a formidable context when I alluded that most of the new love songs bordered on delivering methods of songs from my younger and teenage era, which included the songs of our parents; her grandparents.

‘Intertextuality’ subdued my argument on the current. My thoughts, however, did not stop there, as I reflected that, while growing up, there were songs that told stories that inspired us that our parents or guardians were right; that even when we were not wealthy enough to attend the top pay schools, we explored our inborn skills and talents towards perfecting an industrial trade. But before that, we must and did learn to read. As I mentioned in another article, reading was on the weekly student’s timetable.

I can remember the Calypso, ‘Wayward Boy’. The lyrics were drummed into our consciousness, even as ‘The walkers and riders’. Pickpockets and purse-snatchers were always in the ‘style’, but the lyrics of Wayward Boy resonated even more, “ Tomorrow is misery, when the hangman calls for me, although I’m so young, I will still have to die because of bad company, tell them not to hang me, I’m too young to die, tell them not to hang the wayward boy”.

Then there was another popular tune, this time, a Rocksteady tune that was a Punch Box favourite, ‘Johnny yuh too Bad’, with warning lyrics: “One of these days yuh gonna hear a voice say come, whey yuh gonna run to; yuh gonna run to the rock fuh rescue, but there will be no one, hear my song Johnny, Johnny yuh too bad”.

Then there was another popular tune, this time, a Rocksteady tune that was a Punch Box favourite, ‘Johnny yuh too Bad’, with warning lyrics: “One of these days yuh gonna hear a voice say come, whey yuh gonna run to; yuh gonna run to the rock fuh rescue, but there will be no one, hear my song Johnny, Johnny yuh too bad”.

One of the facts discussed at that time was that our music reflected things that were going on in our society at various levels of influence that needed to be addressed. But just when a generation had grown comfortable with giving Pancho Carew a dollar to send a greeting to a potential girlfriend, Hip-Hop emerged in America. Many of us saw this later genre of its manifestation as a captured effort to distort the Afro-American community, within and without: A music genre had become the anthems of gang bangers; of violence and the missed opportunity to articulate the prevailing social crisis, rather than become consumed by self-abuse. To become the second stage of Black-xploitation entertainment.

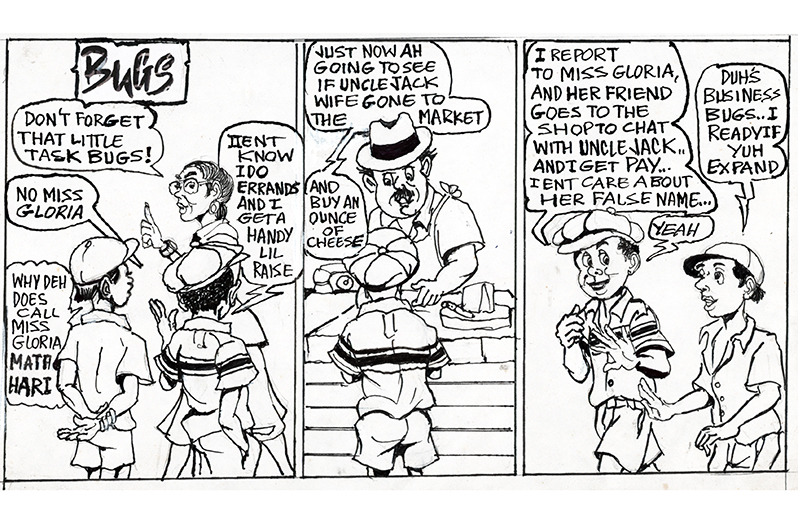

Recently, a young singer on social media said that songs are no longer written to woo women, and he used an alphabet of negative terminologies to describe these women to justify the ‘Why?’. But what I recognised was that the titles had evolved in the lyrics of hip-hop songs. In Guyana and the Caribbean, we had references but different names to emphasise similar narratives. The Mighty Sparrow apologised for his contribution in that era. The terminologies the brother used in this post all evolved from the Hip-Hop idiom. We had other names along the way of my upbringing for folks with certain behaviour.

But let me express a conversation I had with a brother in Harlem in the late 90s. I would go by the Davy’s VEGE SHOP on 125th and this brother usually addressed me as “How yuh doing, Dawg?” We usually chat on social stuff and history. One day, I said, “I prefer you not to use the term ‘Dawg’. I’m a bit uncomfortable with it.” He wasn’t angry, but he inquired “Why?” I explained that this would imply that I’m sleeping with a female dog (the real name is considered an expletive in many circles), then my children are puppies, and we need to be owned and housed in kennels if we’re domesticated enough. He responded, “That’s a lot, but would you mind if I use this in a rap session down the street?” I replied, “Go ahead, bro.” I never saw him again, so I didn’t know how it worked out. Within a few days, I was back in Guyana.

Cultural expressions, whether in music, poetry or conversation, should not be censored unless saturated with vulgarity or socially deemed beyond logic, but we can debate and put issues in music. It’s called civilised expression from the dawn of time.