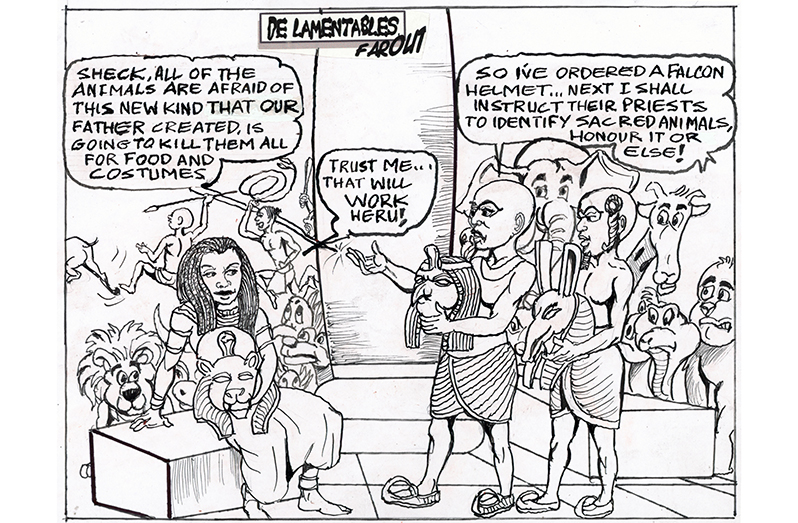

GEORGE G.M. James outlined after his research that the Khemetic Order taught its Grecian brethren the effectiveness of myth as a teaching programme for the common folk to learn the methods of the balance of life. It was not by chance that the Gods each had a sacred animal; this placed a check on hunting into extinction. With the expansion of tribesmen into other areas of Africa, the animals in those realms took this awareness with them.

Nelson Mandela did respond to modern Animal Rights activists who approached him on the subject: “When you [Europeans] came here, they [the animals] were all here, and were in good standing,” he said, adding: “If you want to go and hunt game, it should not be done in a chaotic manner, because we want to preserve the animals. So you must get permission, and the Chief would say, ‘I’m going to have a particular period of the year when you can go hunting.’ So conservation was there long before the Whites came.”

Africa came under a poaching crisis due to Asia’s lust for ivory. In 2011, more than 25,000 elephants were slaughtered mainly for the Chinese market. African countries had to employ counter-poaching squads permitted to shoot to kill poachers to curb that excess. Again, we are seeing stuffed young caimans on our streets for sale in Georgetown. Years ago, when my children were very young, I stopped taking them to the zoo. The issue was that having spent some time in the ‘Bush’, I’ve come to learn a lot from my elders about animals and our responsibility. To return to the ancient world to explain why most of the Khemetic deities wore a specific animal-sculpted headdress no doubt explains that their populations were aware of the need to cultivate a balance between species. They were ahead some ten thousand years ago on the question of conservation.

During the early ’70s, I was a member of a pioneer ‘Young Settlers Group’. This was before the CO-OP college was built. We were allowed some management freedoms; we worked along with the GDF and built the first chicken pens. We proudly placed our chickens in their pens, and were still below the initial budget. The ocelots took advantage of the low-budget mesh on the pens and had a feast. We went to ‘Skipper Gordon’ and asked for firepower to deal with this menace, which had belittled us. He invited as many of us as could hold into his log cabin, and asked how we would feel if some strange folk came into our villages and wards of Georgetown and pushed us out, then built some nice fruit gardens where we once lived. Almost everyone responded, “We got the right fuh tek de fruits, ‘cause deh thief we land.” Then, he expanded on the story, telling us that we were the invaders of the ocelots’ highway forest, and they were the victims. After that little talk, we no longer wanted ‘firepower’; we resorted to rebuilding the pens, using heavy mesh. This didn’t deter the cats, ‘cause they did return. We shone bright lights at them with heavy handheld torch lamps, and they abused us in their screeching, hostile cat language, but they moved on, because they couldn’t get near the chickens. The story the skipper had told us never left us. Most of us grew up with hostility towards the undomesticated creatures of our environment. I became enlightened by seeing the ocelots in the wild.

During the early ’70s, I was a member of a pioneer ‘Young Settlers Group’. This was before the CO-OP college was built. We were allowed some management freedoms; we worked along with the GDF and built the first chicken pens. We proudly placed our chickens in their pens, and were still below the initial budget. The ocelots took advantage of the low-budget mesh on the pens and had a feast. We went to ‘Skipper Gordon’ and asked for firepower to deal with this menace, which had belittled us. He invited as many of us as could hold into his log cabin, and asked how we would feel if some strange folk came into our villages and wards of Georgetown and pushed us out, then built some nice fruit gardens where we once lived. Almost everyone responded, “We got the right fuh tek de fruits, ‘cause deh thief we land.” Then, he expanded on the story, telling us that we were the invaders of the ocelots’ highway forest, and they were the victims. After that little talk, we no longer wanted ‘firepower’; we resorted to rebuilding the pens, using heavy mesh. This didn’t deter the cats, ‘cause they did return. We shone bright lights at them with heavy handheld torch lamps, and they abused us in their screeching, hostile cat language, but they moved on, because they couldn’t get near the chickens. The story the skipper had told us never left us. Most of us grew up with hostility towards the undomesticated creatures of our environment. I became enlightened by seeing the ocelots in the wild.

Reason would assure me that to put one of these animals in a 4’ x 4’ cage as with the zoo was to torture this creature into ‘insanity’. Another experience came to me at Kurupung back-dam. We were then being led by the late ‘Cash Morgan’ when, upon reaching a tacouba (a fallen tree placed across a small tributary waterway etc), one of the crew saw a snake cuddled under the tree at the end of the tacouba and raised the alarm. ‘Cash’ turned around and coldly said to him, “Duh snake mek atemp’ fuh harm yuh? In bush yuh got fuh see t’ing and leff it alone.” With that, we proceeded in silence towards our appointed location.

Years later, I had a discussion with a friend on Laing Avenue about a caiman’s presence in the adjoining canal. I used the same explanation, saying: “Bro, dem t’ings deh heah long before we.” Hubbard looked at me, weighing this strange reasoning, and he responded, “Wuh ‘bout if deh clean de canal more regularly, yuh t’ink dem animal would move on?” The only thing I could do was to agree, “Yeah, bro, I t’ink deh would.” And from that strange, weird moment, the caiman, camoudie and our existence seemed to coincide.

.jpg)