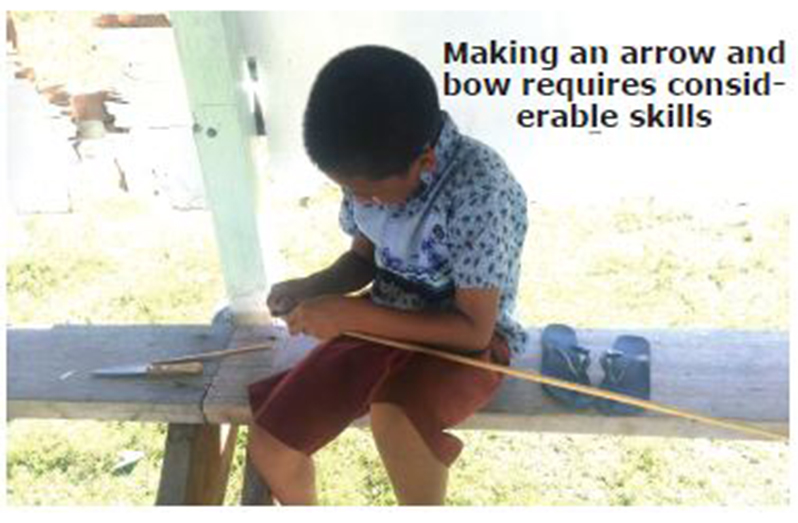

ARROW and bow making is a process that requires considerable skills, knowledge, technique, and practice. As such, the elders in indigenous villages across the country are emphasising passing on this form of traditional knowledge to their youths, which was created many moons ago by their ancestors.

One of the villages that recently held classes to teach children the art was Karaudarnau village in the Deep South, Rupununi.

Toshao of the Region Nine (Upper Takutu/Upper Essequibo) community Apollos Isaacs told Pepperpot Magazine that it is his wish for the village youths to continue their traditional and cultural way of life that their ancestors created years ago.

“The arrow and bow are a great invention by our ancestors which has been passed on from generation to generation and will continue for hundreds of years to come. Traditional knowledge education is important in our communities, especially in these modern times, because if we don’t use it, we may lose it,” he shared.

The arrow and bow is especially used by men, even as some women are also skilled at using it. Men are considered the ‘soldiers’ in villages and the arrow and bow are a sort of weapon which they keep in their possession, and more specifically, whenever they go hunting or to their farms.

“We walk with our arrow and bow just in case there is a jaguar attack, wild animals encounter, wild birds or any other game (bush hogs, labba, bush deer, powis) which we can use as food and provide for our families,” Isaacs related.

The weapon can also be used for fishing as well. “Some men use this while fish hunting in shallow waters using a boat or even at night. It is an essential tool for us as Amerindians since it is easier for hunting. Once released, there is no sound…if the hunter didn’t get the first shot, he could still stand a better chance for a second attempt without noise distractions.”

The Making

First, there is the harvesting of the wild arrow (the plant stalks used). One must be very knowledgeable about when it is ready and mature enough to be used. “They would have to gather a special kind of feather which will be used as the fletching of the arrow. The points will then be made depending on its intended use,” Isaacs explained.

Some arrow points are carved out of wood – some less pointed (mostly can be used for birds and other smaller game) and some with spear-like points which are sharp and durable for bigger games.

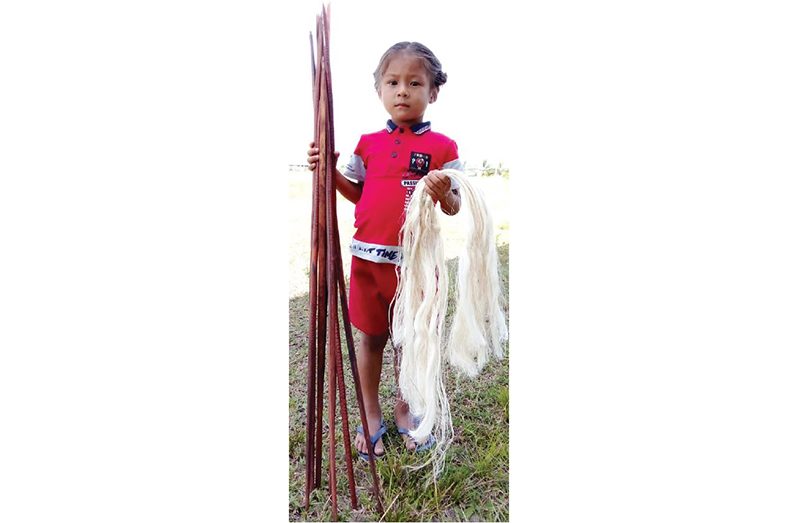

The cordage used for tying any material in this product is locally known as ‘crawah’, a strong, flexible fibre stripped off long sections of fibrous plant leaves, which is a specie of bromeliads (this also requires local knowledge on the correct plant and technique to get the right amount of length and quality of fibres from the leaves).

“Fibres from the cambrium layer between the wood and the outer bark of trees can be used as well but this is less common within the Wapichan tribe. The bows are twice as important as the arrow and require the right knowledge to have very strong and fully functional bow ready for any game at any time. The wood is cured and bent to perfection and polished by hand using other local raw materials and the string is also made with Crawah woven into perfection.

“We ensure that this tradition is preserved by ensuring the younger boys own an arrow and bow at a young age. We make suitable sizes for them, and as they grow, the arrow and bow length increases as well,” Isaacs shared.

The art of making arrows and bows is also taught during programmes such as the South Rupununi Conservation Society (SRCS) traditional knowledge education and other traditional programmes within the village.

During Amerindian Heritage Month, which concluded yesterday, there is usually an archery competition where everyone is eager to participate and show off their skills.

.jpg)