–The obeah story

RELIGION remains one of the most complex areas of defining and attributing good or evil, according to which side of the field of benefits or suffering we’re standing on. Locally, any reference that deviates from one’s catalogue of beliefs is perceived as the other, or, from a colloquial position, as ‘outah‘ or ‘obeah’, especially if the atmosphere fits into the movie imagery of a scary kind of different.

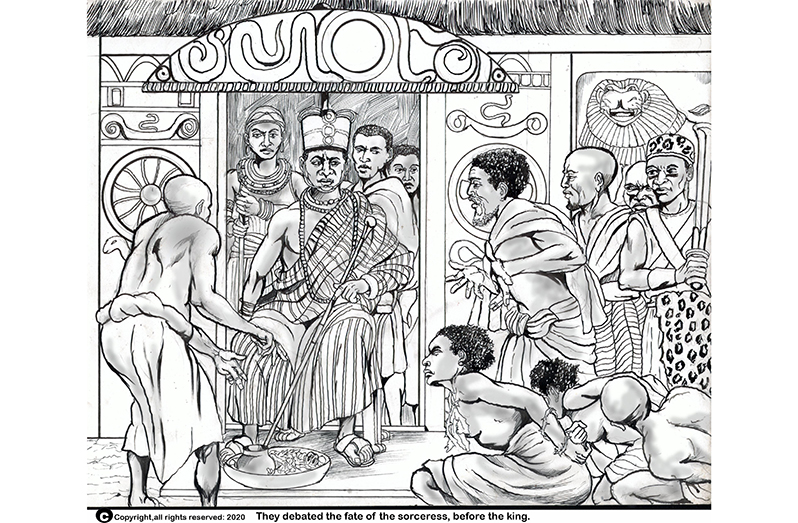

The obeah-man or woman (or wuk-man) in Guyana can be of any ethnicity in our cultural world; it’s what the believer wants that determines who is contacted. In the case of ‘obeah’, we’ve got it all wrong: This is a religion with Gods; proposed energy-enabling forces and rituals. While most of what happens in Guyana is related to sorcery, which consists of acts and deeds that inflict harm on others, and sorcery in Africa, as reported by colonial observations, was subject to execution by beheading, today, isolation in special areas is the punishment for those found guilty of practising it.

The word ‘Voodoo’ means spirit; it is called Candomble in Brazil, Voudou in Haiti, and Obeah in the Anglophone Caribbean. Obeah priests or priestesses are interpreted to be, in most cases, established herbalists and healers. This demonstrates how far the Obeah idea has been disfigured to include everything.

The source of the latest Western (naïve, doubtful but curious) narrative that non-affluent researchers have access to is ‘Volumes I and II of AFRICAN CEREMONIES by Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher’. They described witnessing influences that defy logic: “We were even more mystified when four men drew knives from the calabash fetish and pointed them at a chicken held atop a boy’s head. Within seconds, the bird collapsed, snatching a few shivering breaths before dying. When the chicken was cooked in a calabash, the flammable gourd did not catch fire. How can we explain what we witnessed? We can’t.”

I had some ideas, but could not collaborate, from pointing knives to kill, then a calabash that didn’t burn (Pictures were provided by the authors).

This took me back to an incident that occurred in West Ruimveldt. I was standing next to a young neighbour, watching some drummers doing their thing, when, suddenly, he started to dance literally upside down. I was supposed to be cool, but was stunned. Immediately, two older onlookers ran to ‘West Front Road’ and came back with two buckets of ‘black canal water’ and threw it on him. And as the beat of the drum began to change, the lad gradually came to himself. I have since concluded that ‘Hanta-Banta’, the term used to describe drum-beat possession, and some other things I’ve witnessed over time belong to the preferred to be dismissed, leave-it-alone phenomenon that cannot be analysed.

In Guyana, in most cases when someone uses the term ‘somebody wuk pun he’, it refers to poison, though spirits and even the genie cloud it. This is arrived at after the usual methods have been tried and accustomed symptoms are not identified. In some cases, doctors have have been known to encourage their patients to seek “outside help”, because many medical professionals recognise that though they warn against rash alternative ‘bush medicine’, in some cases, it may just help.

PROFANITY VERSUS SANCTITY

Because of the cultural diversity of our nation, what is considered profane by one cultural group is sanctified by another. Also, in some cases, consultation is not restricted to group loyalty. For instance, though the poisons of botanical and other organic substances are viewed as forbidden in pre-colonial Africa, and punishable by death when used in cases of envy, ‘callous opportunity’, and spite against innocence, poison in collective defence upon related oaths against the concluded enemy seems to be allowed.

Immediately after the 1823 East Coast insurrection, renowned Brazilian historian, Emilia Viotti Da Costa, author of “Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood”, is quoted as saying: “In Demerara, the slaves returned to their day-to-day forms of resistance. Sometime after the rebellion, Joe Simpson’s wife died of poison. Joe, also known as Packwood, was the slave who had betrayed the rebellion to his master on the morning of August 18th. Suspicions of poison were also raised when several soldiers and members of the Militia fell seriously sick after one of the banquets given in their honour. The slaves were defeated, but they had not surrendered.”

‘Obeah’ is the accusing term used across ethnicity and cultures in Guyana, when events that revolve around any incident that involves mysticism and superstition occur.

For example, in 2006, three people perished during a river ritual. Similarly, in February 2015, four people perished in another ritual by the sea. The media, in both cases, elaborated on the context of both events, but the man-on-the-street stuck to obeah business; both were Hindu.

The fact is that the ancients were active in the arts of horticulture, and the effectiveness of certain botanicals; we have inherited that. But today, we are competing to understand also what modern Pharmakeia (the Greek term used to describe Pharmacy, ‘witchcraft’ and ‘sorcery’) in the hands of wealthy institutions bent on population control, biological/industrial warfare, and food control, and debasing mind-altering substances that have eclipsed the age of intent of the ancestors.

.jpg)