–from a new author’s perspective

HISTORY is not static, and with access to new information that was not within grasp or even concealed, a new perspective can be presented towards a better understanding of a foregone concluded topic, with areas left to the imagination and popularly planted touches of sarcasm.

The Book by Marjoleine Kars, ‘BLOOD ON THE RIVER’, retells the historic 1763 revolution with familiar and somewhat new details. My first exposure to the 1763 revolution was through a booklet prepared by my foster grandfather, P.H Daly’s ‘Revolution to Republic 1970’, with an interesting introduction by Martin Carter. My other insight came from the first set of old books I talked myself into being offered to buy.

Youth and enthusiasm can be expensive; these were published in 1960 and sold for ‘a Bob’, or 25 cents. It carried as a series, ‘The story of the slave rebellion in Berbice-1762 Translated from Hartsinck’s “BESCHRYVING VAN GUIANA ECT” By Walter E Roth. They were extremely enlightening. This was informative, but I realised I didn’t have all the books that comprised the entire series. Our local historians, Alvin Thompson, Winston McGowan, Brian L. Moore, Hazel M. Woolford, Walter Rodney, Kimani S. Nehusi, James Rose, and Eusi Kwayana all created a tapestry of linked events to which one can put together a logical timeline and imagery until the Time Machine is created and becomes common.

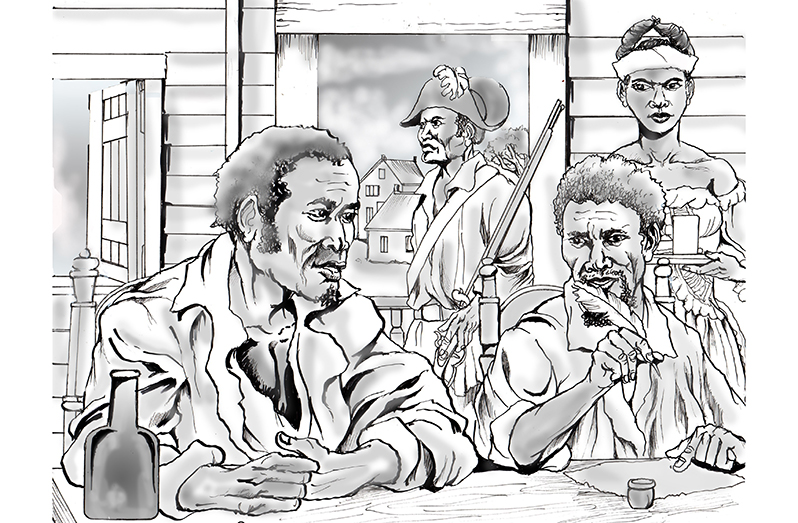

This recent addition from an author that had access to the further Dutch Archives ventured where our historians could not. Thus, this book is a valuable addition to what we know of Kofi and the landscape of activities in 1763. The touted description of 1763 as no mere slave rebellion is further enforced. What did Kofi’s insurrection and revolution in discussions between him and Van Hoogenheim entail? An answer is reinforced, “But kofi {Coffij} was proposing an agreement on a much grander scale. He initiated the negotiations, not the colonial authorities, and he approached Van Hoogenheim as one Head of State to another. His proposal to divide the country in half was unprecedented. Coffij did not offer to retreat with his people to villages in the jungle. Rather, he suggested living with the Dutch as equals; as one nation next to the other. Did he and his men intend to exploit the plantations to trade sugar with the Dutch or other Europeans, as Amina rebels had planned on St. John in the 1730s? If so, they would need access through Dutch territory to the sea. Reportedly, Coffij told Chardon that he wanted ‘free trade’ with any ships that called to the colony. This suggests that he was not after Maroon fashion, but had capitalist-style production and trade in mind. He’d also intended to exchange plantation products from his half of the colony for salted meat and bacon from the Dutch governor. No record remains in which the colonists discuss their reaction to the proposal.

This outlines the scope of vision based on occupying plantations rather than burning immediately at the onset of the 1763 revolution, as one dramatist assumed, using ‘stock anatomy of slave rebellions’ where the enslaved stage a ‘REBELLION’ and burn everything, and flee into the rainforests.

This outlines the scope of vision based on occupying plantations rather than burning immediately at the onset of the 1763 revolution, as one dramatist assumed, using ‘stock anatomy of slave rebellions’ where the enslaved stage a ‘REBELLION’ and burn everything, and flee into the rainforests.

This laziness that becomes the first choice can harm the arts/cultural industry’s interpretations of heritage. Kofi did not understand the predicament that was the impetus behind European colonisation: The need for agricultural and raw products from Africa and Asia. They were no ‘Explorers’; they were all invading Colonizers.

Christendom was a soothing tool. Kofi did not realise that it was not the governor alone that he was negotiating with, but the entire slave-depending new world of the colonising nations of Europe that offered aid, in bodies, ships and supplies to Governor Van Hoogenheim.

Both the governor and Kofi were faced with similar restraints, that of enough food to sustain the conflict, as the rainy season was due. With the governor, his colony staff was in controlled rebellion against his efforts to keep them loyal to the defence of the colony. With Kofi, there were rumblings on the vision he had. There were the creole slaves who had extended families and established their own farmlands. In contrast, as slaves, they wanted the end of slavery, ‘Yes’ they wanted slavery gone, but considered whether they would be allowed to keep their worth in the revolution. For the enslaved just from Africa, any risk towards freedom was worth it, many of them were warriors of subdued tribes, and they weighed that slavery in Africa was much different from European slavery. European slavery and serfdom in Europe and the Colonies were similarly harsh and brutal and, at times sadistic, except for a small percentage of situations.

Incidentally, the treatment of slaves on private plantations was a condition presented to the governor, who represented the company plantations, as one of the main reasons, for the uprising. A copy of this book from Austin is a good buy to view added text with more clarity of the tremendous epic event of 1763, at the beginning of our national history. Happy Republic Day and Mashramani 2023.

.png)