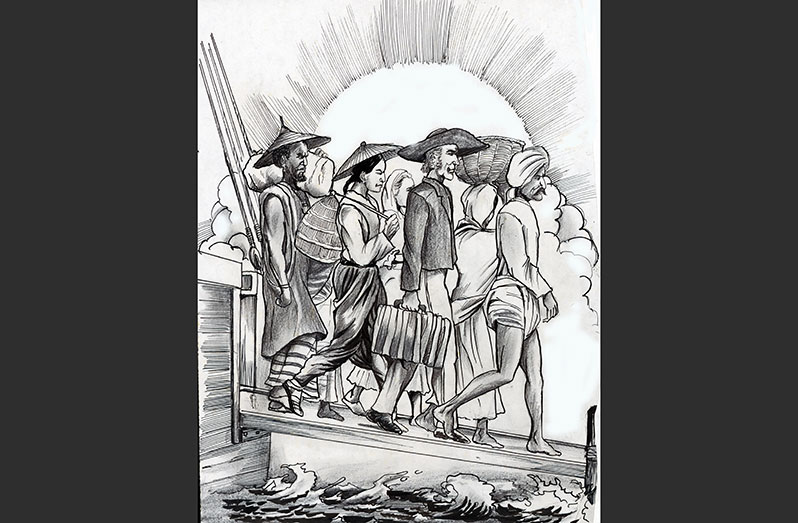

With the advent of Emancipation and the fluctuating fate of Sugar, with the reality of Emancipation, the plantations still needed the consistent workforce of cheap labour. Thus, Indentureship was inevitable, as they faced the new demand for civilised treatment from the abolished Afro-population. For this, the planter-dominated Colonial administration turned to the then British colony of India, colonial decrees in India had affected all aspects of life. The new system of land tenure and the importation of cheap machine-made products from England created more problems. The village handicraft industries suffered terribly. Hundreds of thousands of villagers lost their traditional livelihoods and turned to agriculture for a living, but agriculture was seasonal – see Mangru-Indians in Guyana: apart from caste pressures, with livelihoods lost, thus, the lure of a five-year contract of paid Indentureship seemed an attractive way out for many affected, most came from India’s poorest states, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The first indentured labourers who were brought from India arrived on May 5, 1838. The Whitby and the Hesperus landed with a cargo of 396 persons. Only five per cent were women. Many of the men in assimilating this new world took Afro-wives and, with time, disappeared into the African villages. The Plantocracy corrected that by including an additional number of indentured women with future arrivals. Also, by creating a ‘Boundary Yard’ policy that was put in place to curtail the labourers from leaving the Plantation estate, to be contaminated by Creole values.

Creole values constituted what brought the first labour protest in the colony of British Guiana, which occurred in 1842. Most of the technical estate work was done by manumitted Creoles. Thus, a demand for the rights for higher labour wages, allowances of food and medical support for workers. These privileges were denied by the planters. Then, in 1842, Indentured labour was by that time also brought from Sierra Leone, the West Africans supported the strike, having arrived from a nation that understood slavery, and where liberated slaves were settled when the British outlawed the Atlantic slave trade (1807). They even demanded repatriation based on the betrayed promises of Indentureship (1840-1) though many of them integrated into the existing townships of New Amsterdam and Georgetown, as were the villagers in search of employment (see themes in African Guy-history): The next group of Indentured labour were the Portuguese, arriving from the island of Madeira in 1835. Madeira was stricken by poverty during that period; see ‘The Portuguese Of Guyana’ Mary Noel Menezes: this was a European sugar-growing nation, most likely introduced by the Moors therefore it was construed they would be applicable as effective indentured labour. This did not work from the conclusions of Governor Light; “The Maderians, in particular, proved vulnerable, and Governor Light admitted “they died so fast that common humanity would not let us do it” their importation was discontinued for a while. The fact is that the indentured from India also suffered from Cholera deaths, but there was no consideration halt in their indentured importation. Portugal was different. They were not a British colony but were an ally to British trade and colonial politics; In fact, the indentured Portuguese sent their complaints to their King and not to the English Governor. Thus, the conspiracy to extract them from labour work and use them to neutralise the growing success of manumitted Afro-Business development was convenient. This, in the morbid imagination of the Planters, would force the manumitted Africans back to the plantations, it didn’t work, and it backfired when the King of Portugal intercepted the case where a Portuguese man had killed his Creole wife and was set free (Riots and conflict followed, even the colonial Lawyers lamented this legal outrage). But socially, even though they were benefitting from the links of Portuguese with British royalty, the editor of their paper O Portuguez can be quoted “he habitually denounced the fact that many Portuguese fraternised with Creoles, lived with Black women, and abandoned the Portuguese language in favour of Creole English. Yet, these very social features may have contributed to the ability of the Portuguese to make common cause with the Creole of various strata” see Walter Rodney-A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. The Chinese were at the tail end of Indentureship (1852-91) and were different in the context of their demands and reaction to the colonial planter’s always wrong assessment towards other cultures; the Chinese maintained their gambling and opium-smoking club room, the Creolized Chik-chik board emerged out of the Chinese, the bound yard policy did not quite work with the Chinese, inadequate victuals, brought out a possible other reality of the Chinese, when in gangs they proceeded to raid plantations with cutlasses tied to staffs (similar to a Chinese/Japanese spear) people died, they even proceeded to raid the farmlands of the nearby Afro-Villages, in all most Chinese left the plantations to set up shop in the townships. See-Cultural Power, Resistance and Pluralism Colonial Guyana 1838-1900 by Brian L. Moore. Caribbean labourers did come, but they were also British subjects and were coming to Demerara as free subjects long before Emancipation.

Creole values constituted what brought the first labour protest in the colony of British Guiana, which occurred in 1842. Most of the technical estate work was done by manumitted Creoles. Thus, a demand for the rights for higher labour wages, allowances of food and medical support for workers. These privileges were denied by the planters. Then, in 1842, Indentured labour was by that time also brought from Sierra Leone, the West Africans supported the strike, having arrived from a nation that understood slavery, and where liberated slaves were settled when the British outlawed the Atlantic slave trade (1807). They even demanded repatriation based on the betrayed promises of Indentureship (1840-1) though many of them integrated into the existing townships of New Amsterdam and Georgetown, as were the villagers in search of employment (see themes in African Guy-history): The next group of Indentured labour were the Portuguese, arriving from the island of Madeira in 1835. Madeira was stricken by poverty during that period; see ‘The Portuguese Of Guyana’ Mary Noel Menezes: this was a European sugar-growing nation, most likely introduced by the Moors therefore it was construed they would be applicable as effective indentured labour. This did not work from the conclusions of Governor Light; “The Maderians, in particular, proved vulnerable, and Governor Light admitted “they died so fast that common humanity would not let us do it” their importation was discontinued for a while. The fact is that the indentured from India also suffered from Cholera deaths, but there was no consideration halt in their indentured importation. Portugal was different. They were not a British colony but were an ally to British trade and colonial politics; In fact, the indentured Portuguese sent their complaints to their King and not to the English Governor. Thus, the conspiracy to extract them from labour work and use them to neutralise the growing success of manumitted Afro-Business development was convenient. This, in the morbid imagination of the Planters, would force the manumitted Africans back to the plantations, it didn’t work, and it backfired when the King of Portugal intercepted the case where a Portuguese man had killed his Creole wife and was set free (Riots and conflict followed, even the colonial Lawyers lamented this legal outrage). But socially, even though they were benefitting from the links of Portuguese with British royalty, the editor of their paper O Portuguez can be quoted “he habitually denounced the fact that many Portuguese fraternised with Creoles, lived with Black women, and abandoned the Portuguese language in favour of Creole English. Yet, these very social features may have contributed to the ability of the Portuguese to make common cause with the Creole of various strata” see Walter Rodney-A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. The Chinese were at the tail end of Indentureship (1852-91) and were different in the context of their demands and reaction to the colonial planter’s always wrong assessment towards other cultures; the Chinese maintained their gambling and opium-smoking club room, the Creolized Chik-chik board emerged out of the Chinese, the bound yard policy did not quite work with the Chinese, inadequate victuals, brought out a possible other reality of the Chinese, when in gangs they proceeded to raid plantations with cutlasses tied to staffs (similar to a Chinese/Japanese spear) people died, they even proceeded to raid the farmlands of the nearby Afro-Villages, in all most Chinese left the plantations to set up shop in the townships. See-Cultural Power, Resistance and Pluralism Colonial Guyana 1838-1900 by Brian L. Moore. Caribbean labourers did come, but they were also British subjects and were coming to Demerara as free subjects long before Emancipation.

In closing, the contention with Indentureship from the position of the manumitted creole population was the fact that upon purchasing their villages, they were legally included as taxpayers, which they paid. In response, they would benefit from drainage works from the colony administration. Instead, the authorities used the tax monies to aid in the import of Indentured Labour. The villages suffered from flooding, losing crops and livestock. Even more painful was the infant mortality rate from contaminated waters. The value of the loss of life and property was never addressed but did open a new struggle as the villagers refused to pay taxes. For interested students, the listed books in this column are a good start.

.png)