I MET Compton Dick at the effective bottom house gym in Bent Street called ‘Muscle Craft,’ under the house owned by Mohan, my insurance agent who encouraged me to get into the weight programme. This was the mid-1980s. On learning more about the sport, I realised that it was expensive and, if foolishly driven by that aspect of the ego, could be dangerous. It was about this time that steroids appeared in Guyana, but I liked the health feeling it added to my jogging and the camaraderie. From the beginning, I, however, realised that Compton was different, he was Mohan’s grow mate, and I doubt that in his adolescence, he had ever travelled beyond the wards of Bourda / Alberttown where he hailed from towards any ward in old South Georgetown. One area that struck me was while in gym gaff, I made a reference to architecture; he lit up, up to then I did not know that he was the chief architect at the then Ministry of Housing. The subject was whether ‘Victorian Architecture’ was all English, or whether it was a combination of styles accumulated through Britain’s colonising era. He agreed that it was possible because the book I had brought to score a bet with another gym member, Dasant, (not sure of correct spelling) who was also in the building, showed no similar architecture in the same 18th -19th century Europe. Dick looked through the book, raised his brows, and asked me to borrow it and I refused, on the grounds of the Guyanese sickness of conveniently borrowing, then losing other people’s books. The name of the book is THE LAST OF OLD EUROPE; by AJP Taylor and I was extorted on the price by the late Bourda market book shop owner, Elder De Jonge. We had, however, started a regular discussion on what was and had gone on with local architecture. It seems that Compton was not having a cordial relationship with the administrators of his duties at “housing.” They somehow could not find appreciation for his approaches to the architecture that would have created a totally different air, had it been agreed to in the development of the Housing Schemes.

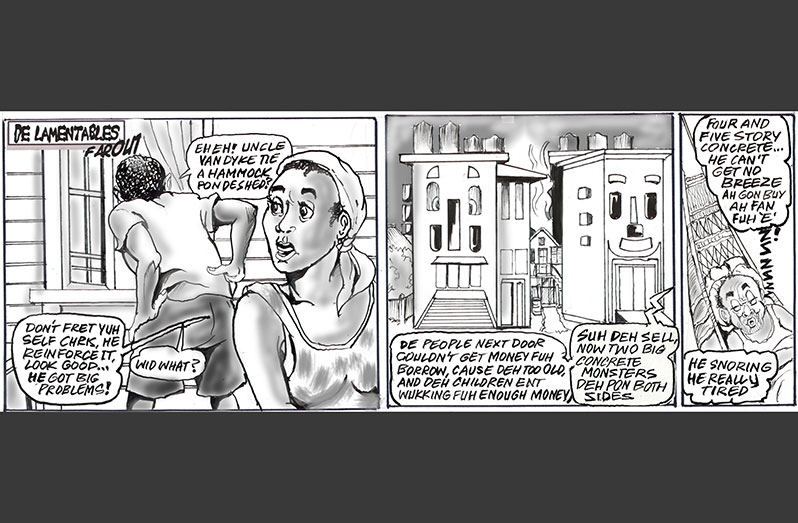

Mohan had briefly confessed to me about some unfortunate disruptions that Compton had experienced that had led to his often-broody mood, which apparently existed at a lower level before. But I then adopted an approach of engagement which worked; the thing is, I liked Technical Drawing, which is the ABC towards conceptual architectural design. I do think that the ranges of East-West Ruimveldt and other schemes could have been more people-friendly than the heated cell blocks they are-were. Not because there’s a need for housing should mean anything goes. Diverse interests fragmented the gym crew, and more than that, the Mohans departed for the US of A. It had brought that chapter to a close. But somewhere between the end game of the Gym, Compton had become dislodged from the Ministry of Housing. A close brethren who worked under Compton returned recently to Guyana, and Compton came up after I commented on a colonial building on Craig Street. It was night, and I could hardly perceive its definitions. The brother said, “ They mocked Compton at “housing.” They called him the ‘mud-hose architect,’ because he indicated more of that in the design for housing designs.” Pointing at the Craig Street house, I concluded, “Rather than the concrete pillboxes, that are now everywhere, even in areas like Alberttown where the cesspit problems have remained troublesome to residents for decades.” Shortly before Compton, I presume, had retired, he gave me a short essay he Compton had composed, concerning his philosophy of architecture with reflections on Rudolf Steiner titled “Some Thoughts on the Politics behind the Steiner Argument,” with a background to Steiner’s Anthroposophical movement. The document was handwritten, on pastel pink 28lb paper. I viewed it briefly, then filed it, not sure of how to contextualise its content into a local working tool, after understanding Compton’s calligraphy, and forgot it. But when I unearthed it after moving some years ago, I recognised that Compton and the gym crew had in conversation argued many of these ideas, like the relevance of local design, whether in graphic arts, literary language or architecture, must reflect the aesthetics of our evolution. I was wrong to think that he had just become inclined to this 20th-century German philosopher mystic, whose arguments, at a closer look, existed in the fount of all civilisations, adjusting and expanding to inhabit local geographical and cultural interpretations. In contrast to Guyana today, Compton was way ahead. We have become a township of alien concrete Pillboxes that should have emerged in a specific ‘Commercial-site’ similar to; but more elegant than the old Ruimveldt Industrial site, rather than in the core of residential Georgetown’ emerging in every ward and imposing on every humble yard.

Mohan had briefly confessed to me about some unfortunate disruptions that Compton had experienced that had led to his often-broody mood, which apparently existed at a lower level before. But I then adopted an approach of engagement which worked; the thing is, I liked Technical Drawing, which is the ABC towards conceptual architectural design. I do think that the ranges of East-West Ruimveldt and other schemes could have been more people-friendly than the heated cell blocks they are-were. Not because there’s a need for housing should mean anything goes. Diverse interests fragmented the gym crew, and more than that, the Mohans departed for the US of A. It had brought that chapter to a close. But somewhere between the end game of the Gym, Compton had become dislodged from the Ministry of Housing. A close brethren who worked under Compton returned recently to Guyana, and Compton came up after I commented on a colonial building on Craig Street. It was night, and I could hardly perceive its definitions. The brother said, “ They mocked Compton at “housing.” They called him the ‘mud-hose architect,’ because he indicated more of that in the design for housing designs.” Pointing at the Craig Street house, I concluded, “Rather than the concrete pillboxes, that are now everywhere, even in areas like Alberttown where the cesspit problems have remained troublesome to residents for decades.” Shortly before Compton, I presume, had retired, he gave me a short essay he Compton had composed, concerning his philosophy of architecture with reflections on Rudolf Steiner titled “Some Thoughts on the Politics behind the Steiner Argument,” with a background to Steiner’s Anthroposophical movement. The document was handwritten, on pastel pink 28lb paper. I viewed it briefly, then filed it, not sure of how to contextualise its content into a local working tool, after understanding Compton’s calligraphy, and forgot it. But when I unearthed it after moving some years ago, I recognised that Compton and the gym crew had in conversation argued many of these ideas, like the relevance of local design, whether in graphic arts, literary language or architecture, must reflect the aesthetics of our evolution. I was wrong to think that he had just become inclined to this 20th-century German philosopher mystic, whose arguments, at a closer look, existed in the fount of all civilisations, adjusting and expanding to inhabit local geographical and cultural interpretations. In contrast to Guyana today, Compton was way ahead. We have become a township of alien concrete Pillboxes that should have emerged in a specific ‘Commercial-site’ similar to; but more elegant than the old Ruimveldt Industrial site, rather than in the core of residential Georgetown’ emerging in every ward and imposing on every humble yard.

In closing this first part tribute to Compton Dick, I leave with this reference by John P. R. Falconer, extracted from a paper on the use of wood in housing held in Canada 1971, that reflected Compton’s argument of using wood rather than cement in local domestic building. “Technicians from industrialised countries may lay too much stress on purely physical considerations and material comfort and be quick to introduce technological improvements. It is clear that housing solutions in developing countries, except for the elite minority, cannot afford the luxury of air conditioning or expensive architectural devices such as double roofs, brise-soleil, or heat-absorbing glass. Uncomfortable gain, storage, and emission of heat must therefore be kept within reasonable limits by the application of climatic and biological principles to planning and design, and by the selection and use of building materials based on their thermal characteristics…” confirming Compton’s argument.

.jpg)