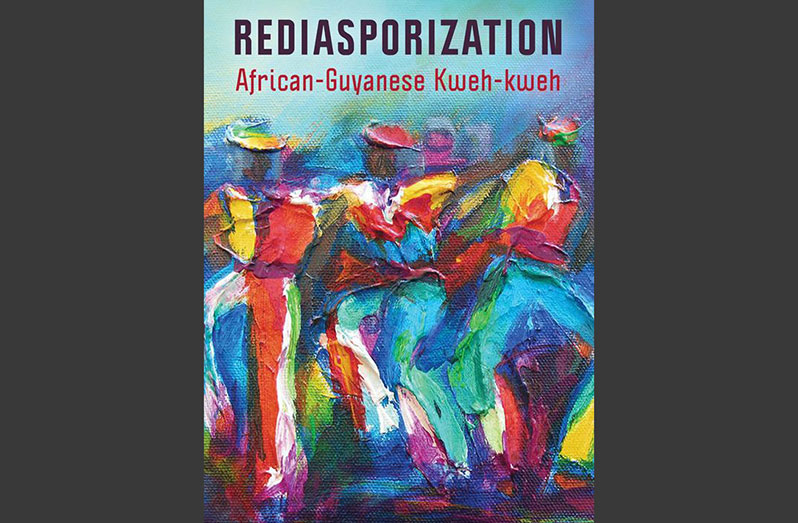

OVERSEAS-BASED Guyanese, Professor Gillian Richards-Greaves at Coastal Carolina University, has recently produced a fascinating and captivating book titled Rediasporisation: African-Guyanese Kweh-Kweh. The book examines the ways African-Guyanese in New York City use Come to My Kwe-Kwe to negotiate complex, overlapping identities in their new homeland, by combining past and present elements and reinterpreting them to facilitate and ensure rediasporisation. Specifically, it examines rediasporisation through discourses of food, gender, music, dance and religion as well as demonstrating how Come to My Kwe-Kwe performances in the United States have facilitated African-Guyanese transformation from an imagined to a tangible community.

Lomarsh Roopnarine (LR): When did you start writing this book?

Gillian Richards-Greaves (GRG): I started writing this book in 2012 when I finished the final version of my dissertation.

LR: Can you explain the title of the book by addressing what is Rediasporisation?

GRG: Rediasporisation refers to the creation of a newer diaspora from an existing one. Thus, African-Guyanese is one population segment of the larger African diaspora brought from Africa to work on the plantations in Guyana. In the modern period, they have migrated to the United States, forming an African-Guyanese diaspora that includes their original homeland (Africa) and a secondary homeland (Guyana).

LR: What is African-Guyanese Kweh-Kweh?

GRG: Kweh-kweh, also known as karkalay, mayan, kweh-keh, and pele is a uniquely African-Guyanese pre-wedding ritual that emerged from enslaved Africans in Guyana. The ritual historically functioned as a medium for matrimonial instructions for soon-to-be-married couples. It allowed the community to comment on the bride, the groom, and their nations (relatives, friends, and representatives), and highlight the underlying values of the community. A typical kweh-kweh has approximately 10 ritual segments, which include the pouring of libation to welcome and appease the ancestors; a procession from the groom’s to the bride’s residence; the hiding of the bride; and the negotiation of bride price. Each ritual segment is executed with singing and dancing, which enable participants to chide, praise, and tease the bride and groom and their respective nations on conjugal matters, such as sex, domestication, submissiveness, and hard work.

LR: Can you briefly take readers through the migratory journey and cultural dynamics of Kweh-Kweh through triangular process of Africa, Guyana and US?

GRG: The traditional kweh-kweh ritual is informed by indigenous marriage customs and puberty rites of passage in West Africa and cultural mixing in Guyana.

Kweh-kweh rituals are an all-night affair in which the entire community in Guyana is involved. Attendees sing and dance, as they offer advice, instructions, and warnings to the bride and groom, or simply poke fun at them and their nation. This jollification is fuelled by a variety of Guyanese foods, such as cookup rice, metemgee, diverse local drinks and spirits. In the United States, African-Guyanese continue to celebrate the traditional kweh-kweh before an impending wedding, but they are often compelled to modify ritual elements to accommodate the laws of their new homeland and a changing Guyanese community. Thus, many processions have been shortened, such as the long-distance between the bride and groom, as well as noise ordinances preventing the all-night celebration and beating of drums.

LR: What role does the audience play in Kweh-Kweh?

GRG: Come to My Kwe-Kwe is celebrated on the Friday evening before Labour Day and replicates the overarching segments of the traditional (wedding-based) kweh-kweh. However, a couple (male and female) is chosen from the audience to act as the bride and groom, and props simulate the boundaries of the traditional kweh-kweh performance space, such as the gate and the bride’s home.

GRG: Come to My Kwe-Kwe is celebrated on the Friday evening before Labour Day and replicates the overarching segments of the traditional (wedding-based) kweh-kweh. However, a couple (male and female) is chosen from the audience to act as the bride and groom, and props simulate the boundaries of the traditional kweh-kweh performance space, such as the gate and the bride’s home.

LR: My reading of your book suggests that Kweh-Kweh is a fading African-Guyanese cultural tradition in Guyana. Is that so?

GRG: Kweh-Kweh started fading in the late 1980s, during the economic downturn in Guyana, particularly in areas outside of villages. Nevertheless, since the mid-1990s, there has been an uptick in kweh-kweh performances, possibly due to the political climate in Guyana, which has forced many African-Guyanese to return to their roots.

LR: I like how you used food, mainly Cookup Rice, to show the reconstruction of Kweh-Kweh from Guyana to New York. Why do you think this is a crucial culinary space to explore and express Kweh-Kweh?

GRG: For African-Guyanese, the kweh-kweh ritual is a space where they reaffirm and display their Africanness and Guyaneseness through diverse cuisines. While all kinds of “Guyanese foods” are served at kweh-kweh, African-influenced foods, like cookup rice, are regarded as indispensable. Cookup rice made with blackeyed peas is often viewed by African-Guyanese as “ancestral food”. In the United States, cookup rice and other Guyanese cuisines are the food voice through which African-Guyanese and others recall past memories and experiences, create new realities, and articulate individual and group values and identities.

LR: Can you share some thoughts on how African drumming, dancing, and music have maintained Kweh-Kweh in form, function, and fascination in New York City?

GRG: Accompanied by the rhythms of stomping of feet, “found sounds” (objects used as instruments), synthesizers, djembes, and an assortment of percussive instruments, attendees at Come to My Kwe-Kwe sing traditional kweh-kweh songs, Guyanese folk songs, and musical genres from around the world. They sing using coded language, double-entendre (double meaning), and unmasked (raw) speech. As attendees sing and dance in the ganda (performance space), they address diverse matrimonial topics, particularly sex. Some African-Guyanese view the drums as a distraction and often complain that Come to My Kwe-Kwe singing should only be accompanied by the rhythms of the stomping feet and found sounds. Nevertheless, attendees understand that the songs and dances performed and innovated at Come to My Kwe-Kwe are done to entertain, instruct, and educate the African-Guyanese diaspora in New York City, and, in so doing, keep the kweh-kweh ritual alive.

LR: What role does religion (African animism/spiritualism, Christianity, syncretic) play in the rediasporisation of Kweh-Kweh in New York City?

GRG: In the context of Come to My Kwe-Kwe in New York City, the complexity of religious values and ethnic identity negotiations collide with varying outcomes. Some who embrace African-Guyanese culture but reject the religious undertones of the ritual, such as the beating of drums or the pouring of libation, might remain on the peripheries of the ganda (the performance space) or participate in select practices. Others who seek the mental reprise from religious doctrines that bind them to their faith and prevent them from embracing their Africanness, reinterpret scriptures to suit the performances they participate in. For many, however, participating in Come to My Kwe-Kwe requires them to “borrow a day from God” to sing, dance, and gesticulate in manners they would ordinarily regard as “outta ardah” (unseemly), and, to do so on the Sabbath.

LR: Apart from what is shared here, what would you like readers to know about your book?

GRG: The process of rediasporisation is not limited to the African-Guyanese diaspora but is applicable to all diasporic groups. Moreover, this book compels us to look beyond the surface of single ritual practice, investigate seemingly defunct elements, and make broader connections within humanity. By examining a single ritual, I was able to reveal the embedded values of a community and understand how migration complicates those values, changing people and ritual in the process.

LR: You have done an excellent job in weaving and negotiating a good deal of different complex cultural elements and overlapping belief systems, and identities in African diaspora from the past to the present to show how Kweh-Kweh has been rediasporised in New York City that would, in my mind, certainly survive. Thank you

.jpg)