–US-based Guyanese historian contends

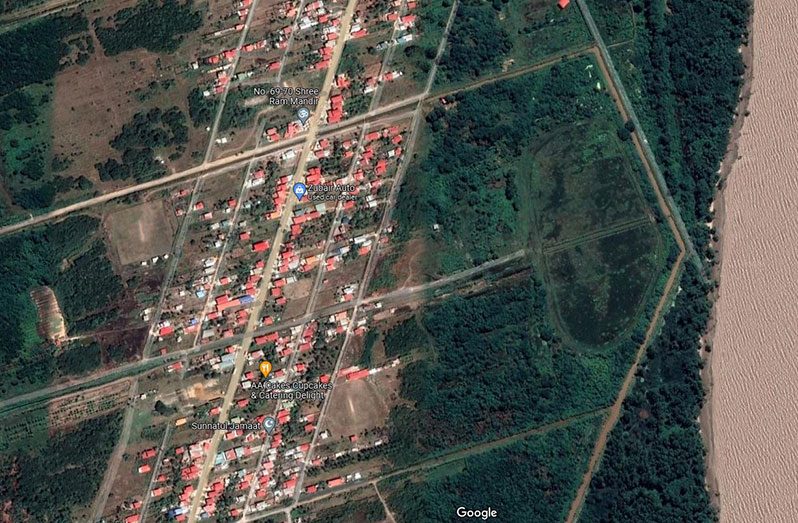

WHILE there is still no clarity following the discovery of wooden coffins with bones protruding from the heavily-silted foreshore of Little Massiah (No. 71 Village), Corentyne, a US-based Guyanese professor believes the ‘shallow’ burial ground could have been privately owned.

It is believed that these persons died from a pandemic.

“It is unclear what the race of the persons was, but it is certainly people of the higher class,” said Professor Lomarsh Roopnarine, a Guyana-born historian attached to the Jackson State University, a public university in Jackson, Mississippi.

“It is presumed that these might not have been people who are anchored in that location, but they might have just settled there for the time,” the historian, who spent his childhood close to the discovery site, told the Guyana Chronicle in an interview on Monday.

The historian was cautious about noting that these were just his thoughts and not matter-of-fact conclusions, as he intends to conduct further research on the subject. He did observe, however, “The coffins had to be built for persons of the higher class, because the wood is pinewood; had to be imported, and could not have been done by working-class people.”

He believes the bones found were neither persons of African nor East Indian descent. “People who settled in these areas a hundred years ago were Indian Indentured servants; however, the persons buried might not have been indentured servants, because their bodies would have been burned, as is done now. Burying, at the time, was not part of Hindu customs,” Professor Roopnarine said.

The coffins that have been found might have also contained the bones of children, Roopnarine contends, as some of the wooden boxes are small in size. It is believed that their deaths were caused by pandemic or epidemic-related illnesses affecting Guyana during its colonial days. He would not, however, speculate on the period these coffins and the cadavers were first buried, as is being done in the public now since the discovery emerged on social media.

“It could be that they all died in a close period of time,” Professor Roopnarine alluded. “The young children might have experienced a pandemic; the bodies were placed into pine boxes, with the intention of preserving them,” he added.

Over the last 200 years, and especially in the early 1800s to early 1900s, what was then British Guiana dealt with a number of deadly diseases. Proper sanitation in the colony of British Guiana, and elsewhere in the British empire, was virtually non-existent up until public outcry and state-supported investigations at the turn of the 20th Century. Pemberton (2003) writes that the colonial period was marked by a heavier focus on profits from the plantations than on health and sanitation, which were considered as “welfare” and not necessary.

With the arrival of cholera in Great Britain in the 1830s, De Barros (2003) reports, governments in the West Indies were advised to create Boards of Health, and adopt quarantine and other sanitation measures. British Guiana co-operated, and by 1852, different variations of the Colony’s public health law were established, with Local Government bodies having more control over sanitation and public health.

By the 1920s, more influence was placed on community-based sanitary improvements, as diarrhea and enteric fever (typhoid), called ‘dirt’ diseases at the time, had contributed to deaths throughout the colony. Contaminated water and milk were blamed, as well as the poor management of garbage and sewerage.

“The pandemic does not discriminate against class; but burial does,” Professor Roopnarine noted, adding:

“They might not have wanted their children to be buried with other children.”

Another telltale sign for him is the size of the coffins. “The graves are shallow; this explains why this might be a private cemetery. This burial did not follow the regulations of the State, because six feet would have been required.”

According to the Jackson State University website, Professor Roopnarine’s field of study is interdisciplinary, drawing on methods and concepts in history, sociology, economics, and environmental science. His current research involves migration within the Caribbean, and between the Caribbean and the global north.

.jpg)