The Painful History of Industry

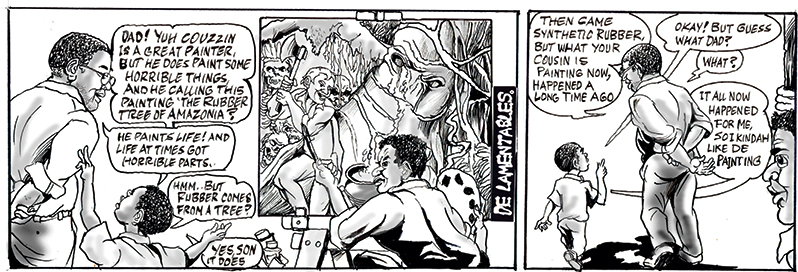

SOME things are learnt not by intent, but by the imposition of elders that to sit in their conversation you must ‘know’ at least this much. There’s a category of study in the area on the History of Industry that should be developed. This inspiration came to me through a conversation I had with a citizen whose academic boasts are less irritating than the arguments to defend what he does not know. However, the last conversation we had was based on our economy and the ‘six sisters’ reference by then-President David Granger to our colonial inherited economy and why I think he was right, and why his critics had missed the bus. I used an argument only to realise that none of the three other persons had ever encountered what I was referring to. It’s a Brazilian story and it revolves around the colonising and industrialisation, in a way, of vast Amazonia over the past centuries. Brazil had emerged at the top of the food chain when it came to the product of ‘Borracha’ as the gum of the Rubber tree is called, before synthetic Rubber. Back in the 19th century with the Industrial Revolution from the 1830s onward. Rubber became a major ingredient of that era, more profitable than the Sugar plantations of Bahia with its numerous enslaved Africans.

The thing with the rubber trees was that they grew in the dense Rain forests of the Amazon, the domain of numerous Amerindian tribes. But with every member of the elite caste of the human potpourri of Italians, Germans, Japanese and Portuguese Brazilians wanting to own a rubber plantation and become a ‘Seringalista’ the problem lay with neutralising the Indian tribes, so they adopted Genocide; through enslaving, using poisonous gifts of clothing like the Americans, and shock troops of killers, machined gunned from Aircrafts the most lenient were the missionaries; the Indians were not passive and they fought back, but they were isolated, hundreds of years behind the methods of warfare used against them so they were at a disadvantage, entire tribes were exterminated. A narrative at the time of the first publication of this text in 1969 referred to the Indians as follows “They would rather die than work – so they died, or were put to death. There used to be two, three, four million of them in Brazil. How many are left? Barely 200, 000, or 300, 000 in the entire country” In Guyana we grew up hearing of the dangerous tribes of the Amazon, head hunters, saw pictures of shrunken heads, cannibals etc. but never of the onslaught of the colonising elite. Media can be elusive.

The monopoly of Brazilian rubber was viewed not with fiscal admiration by all the then western world of colonizing nations. Thus, Henry A. Wickham a respectable English businessman with links to Her Majesty’s Secret Services as part of a group was dispatched to Brazil, though he and their movements were watched, no one anticipated that he would identify against dangerous natural obstacles a location which was deemed impossible to traverse because in the rainy season with 50-foot high floods that submerged vast areas, it was concluded who would dare? So the Brazilians relaxed their vigilance and Wickham dared, he navigated through the natural barriers to a location populated by Rubber trees and he and his commando group selected and collected as many seeds as necessary. Wickham eventually departed Brazil for British Malay. It would take 36 years later for the verdict of Sir Roger Casement [1913] and his commission on the Putomayo to condemn the atrocities against the Indians. A call if you would like to see it that way, to civilized nations on the fate of the Brazilian latex [a direct result of Wickham’s commando act] “1913: The 2,800 seeds filched by Wickham had become tame forests, forests subject to the will of man; not the adventurer any longer, but the engineer, the botanist and the financer. Rubber at one’s disposal, to traverse because in the rainy season with 50-foot high floods that submerged vast areas, it was concluded who would dare? So the Brazilians relaxed their vigilance and Wickham dared, he navigated through the natural barriers to a location populated by Rubber trees and he and his commando group selected and collected as many seeds as necessary.

Wickham eventually departed Brazil for British Malay. It would take 36 years later for the verdict of Sir Roger Casement [1913] and his commission on the Putomayo to condemn the atrocities against the Indians. A call if you would like to see it that way, to civilized nations on the fate of the Brazilian latex [a direct result of Wickham’s commando act] “1913: The 2,800 seeds filched by Wickham had become tame forests, forests subject to the will of man; not the adventurer any longer, but the engineer, the botanist and the financer. Rubber at one’s disposal, which could be improved like a breed of poodles, and which was led by teams of coolies supervised by a few white men. Colonization had killed Barbarism. It was Singapore’s turn to be the city of Billionaires-much better-policed ones, white and yellow alike, than those of Manaus! It was a time of trusts and dividends. This was something of quite different dimensions, and the “boom” that people had longed for would last at least until the appearance of synthetic rubber. But now, in 1913 as far as Amazonia was concerned, the adventure was over” GREEN HELL Massacre of the Brazilian Indians by Lucian Bodard [English edition 1971].

I often wonder if those local scribes who now and then refer to Singapore know of that aspect of their ‘economic history’? The waterfront of Guyana thrived, supplying jobs to thousands and perks from breeched crates heading for other ports. How could it not have crossed minds that drastic measures should have been taken to revolutionise the thinking in the expectation that shipping would be modernised and the workforce shrunk to protect shipping worldwide. Likewise, Sugar competing with beet and the Anti-Sugar ‘Health Cry” should have heralded the wakeup alarm, long before the EU mandate, With Bauxite’s by-products new joint areas of employment could have emerged. In all of this, the impact of the global Oil crisis of the 70s was an even more severe warning; all in all, we should have learnt something and hence should pay more attention to sustaining what is, because, come hell or high water, change will come.

.jpg)