2020 marks one hundred years since Indian labourers have been released from the jaws of plantation indentured servitude. This state-sponsored contract labour system began in 1838 and continued until 1920, albeit with a checkered existence. The labour system was instituted by the British government and supported by the planter class to supplant the loss of slave labour following emancipation in the middle of the nineteenth century. Despite the positive recommendation from the Sanderson Commission of Enquiry to continue the system, the British and Indian colonized governments pulled the plug on indentured labour primarily because it proved to be abusive to the labourers and unprofitable to the managerial plantocracy, among a host of anti-indenture campaigns in South Africa and India.

Over two million Indians were shipped out of the Indian sub-continent to provide labour in European-owned colonies of Mauritius, South Africa, Fiji, Reunion, and the southern Caribbean. Of this total, 500,000 were shipped to the Caribbean. An estimated 350,000 Indians remained when their contracts expired, choosing to exchange their entitled return passages for settlement and subsequent citizenship, while 175,000 of them returned home, echoing ameliorative and retrograde sentiments, and, in so doing, fractured the notions of indenture as a collective experience. Then we have this unusual aspect of indenture. An estimated 50,000 of the returnees arrived in the Caribbean for a second time which ironically inverts conventional thinking as to why these labourers would want to return to a system deemed as monstrously evil.

Naturally, one would expect some events from the descendants of indentured labourers to commemorate this momentous occasion. Since March of this year, numerous virtual meetings, workshops, conferences, and lectures have proliferated across former indentured communities and further afield. These platforms have provided a unique epistemological opportunity, essentially calling on the practitioners of Indian studies to turn the camera onto themselves to re-examine pan-indenturism, 100 years later. Remarkably, some productive initiatives have emerged from these virtual platforms, namely, book proposals, new journals, scholarly papers, chapters, institutions, and, of course, plans for inter-connectedness among former indentured regions and academics. These initiatives, when materialised, will continue to move the study of indenture from the margin to the mainstream of world history and literature. We hope. More steadfast efforts are needed, of course, to bring the field to a desirous standard of recognition.

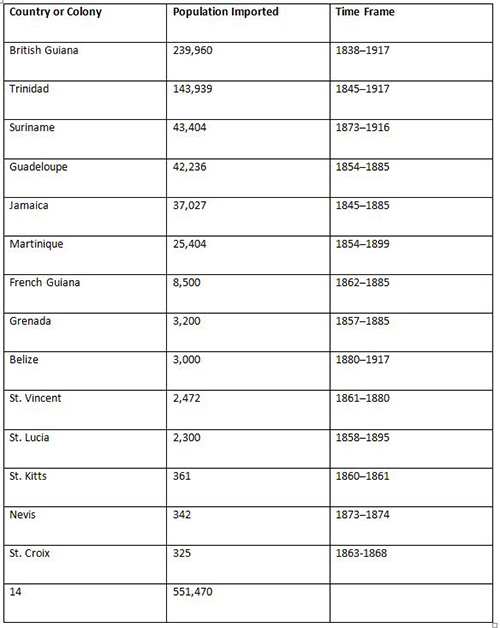

In this process, certain questionable information of indenture should not be seamlessly transferred on the world academic stage as discourses and empirical knowledge. In this limited space, I suggest that the available statistics of the indentured population deserve the utmost renewed attention because it would help us to understand the subject more deeply and arrive at informed conclusions. For example, at a macro-level, we are not sure how we have arrived at the figure that 500,000 indentured Indians were brought to the Caribbean and that 396 or 409 Indians were on the two separate shiploads to British Guiana in 1838, on a micro-level. These are blind spots in the study of pan-indenturism. Below I provide a table of the statistics and time frame of indentured Indians shipped to the Caribbean to jump re/start the process without repeating past mistakes.

These figures were compiled from archival and secondary sources. The movement of Indians during the above time-period was not fluid. There were a series of commencements, stoppages, and resumptions during the time-period for each country, revealing the instability, unreliability, and underbelly of indenture as a panacea for solving post-emancipation labour challenges. Three quick points should be noted regarding the table. The only shipload of Indians who were brought to Nevis has not been documented in the secondary sources, while in the Belize case Indians were brought there in two waves, first from India directly to Belize and then from India to Jamaica and then to Belize. Most Indians in the Caribbean were plantation indentured labourers but those who were taken to French Guiana worked in the goldfields, called placers, deep in the forest interior region. The death rate among the French Guiana indentured Indians was the highest in the Caribbean (lomarsh.roopnarine@jsums.edu).

.jpg)