–gov’t spent as much as $60+M in 2019 alone

THE Government of Guyana has expended some $60 million in 2019 on Non-Governmental Organisations involved in providing housing for adult female victims of trafficking.

It also opened the country’s first shelter outside of the capital, Georgetown, for victims of the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) trade, and expended another $2 million on providing direct financial assistance to those victims who did not stay in a shelter.

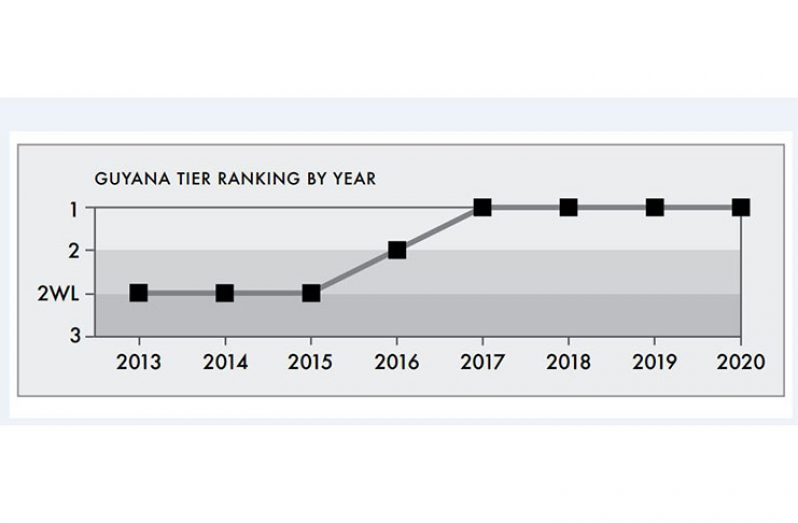

This was disclosed in the US State Department’s 2020 TIP Report, where, for the fourth consecutive year, Guyana has maintained its Tier 1 ranking, meaning that the country has fully met the minimum standards for the elimination of TIP, and demonstrates serious and sustained efforts to address the social issue.

Tier 1 is the highest attainable ranking in the four-level system, where Tier 3 is the lowest ranking, representing countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards, and are not making significant efforts to do so to deal with the issue of TIP.

Prior to 2017, Guyana was ranked a Tier 2 country, which was back in 2016, while prior to that it was listed as a “Tier 2 watchlist” country, which is the ranking just above Tier 3.

The report considers measures taken to address both sex and labour trafficking, but notes that limited government presence in the country’s interior renders the full extent of trafficking unknown.

Notwithstanding the active efforts, however, according to the report, greater effort is needed in the handling of TIP situations involving male and child victims, as well as a need for more accountability and culpability of officers and others in authority who, instead of protecting victims, compound the situation. There has also been a lack of effort by the government to reduce the demand for commercial sex.

According to the report, for 2019, a total of 102 victims were identified, which was a significant improvement on the 156 and 131 identified in 2018 and 2017 respectively. Of the 102 victims, 95 were female, and seven male. Among the lot were 10 minors, according to the report.

Twenty-five calls made to the national hotline resulted in trafficking investigations during the reporting period. However, according to the report, the three new prosecutions of suspected traffickers in 2019 was a reduction from 11 prosecutions in 2018, and 17 in 2017.

In the case of minors, the authorities reported six child-labour violations, with citations issued for two such violations in the extractive and service industries, and criminal charges filed in the two cases of child-sex trafficking.

The victims came from Guyana, as well as the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Venezuela.

“The MoSP funded transportation costs and police escorts for victims staying outside a shelter who were willing to attend court proceedings, and granted deportation relief to 135 foreign victims. The government reported granting foreign victims temporary residence status and work permits, if requested,” the report noted.

ADDRESSING CHILD LABOUR

For the reporting period, several initiatives taken by the government to actively address child-labour issues.

“Labour officers frequently conducted impromptu visits to work sites and business premises in the mining and logging districts and capital city to investigate suspect labour practices and possible violations. The government drafted a National Action Plan to Eliminate Child Labour to deal with challenges in recruiting, retaining, and training labour inspectors to more effectively monitor child labour and extractive industry workers, particularly in light of Guyana’s fast-growing oil operations where children are particularly vulnerable to forced labour,” the report noted.

Other commendable implemented measures highlighted in the report as demonstrating “serious and sustained efforts” included the completion of a draft amendment of the Combating Trafficking of Persons Act; the sentencing of a convicted trafficker to 15 years imprisonment; drafting a national action plan to eliminate child labour; and the completing of standard operating procedures for investigating and prosecuting trafficking cases.

The government trained 221 law enforcement officers on trafficking victim identification and referral procedures, and 48 judicial officers on standard operating procedures for prosecuting human trafficking cases, with the assistance of international organisations during the reporting period.

However, in terms of areas still in need of improvement, the report noted that the country “investigated and prosecuted fewer suspected traffickers, identified fewer victims of trafficking, and did not provide adequate screening or shelter for child and male victims”.

The report said there is a need for more labour inspectors and increased training in human trafficking, and the need for reduction in the delays in court proceedings and pretrial detention of suspects, pointing out that “prosecution cases took an average of two years in process and pretrial detention averaged three years”.

In terms of prosecution, the report also noted that “minimal law enforcement efforts” were maintained by the government, while in terms of protection the government was chided for “inadequate efforts to protect victims and identified fewer victims”, while “victim assistance remained a serious concern”.

The report was emphatic about the need for more accountability of officers and others in authority who misuse their power. The report called for “police and law enforcement officials accountable for abuse of vulnerable individuals and intimidation of victims in shelters”.

“The government did not report any new investigations, prosecutions, or convictions of government employees complicit in trafficking offenses, although the government screened Venezuelan women and children who experienced human rights abuses, including sexual exploitation by government officials,” the report said.

The report called for police and law enforcement officials to be answerable for abuse of vulnerable individuals and intimidation of victims in shelters

“Observers noted there were frequent, widespread reports of physical and sexual abuse of children and allegations that some police officers could be bribed to make such cases “go away”. Observers reported police and other authorities intimidated some victims into staying at shelters against their will, did not allow family visits until trials were completed, and cut short some victims’ phone calls if they spoke in their native language,” the report said.

.jpg)