THE awareness of a common identity amongst the citizens of a country is referred to as national integration. Despite our varying ethnicity, language, cultural and spiritual practices we are cognizant of the fact that we are all ONE. In a previous column, I mentioned that art has an innate ability to create an appreciation of diversity in a multicultural society. Every time I visit an exhibition this concept is further understood.

The Moving Circle of Artists Retrospective Exhibition (1988-2019) currently at The National Gallery of Art, Castellani House, has captivated me in more ways than one. Today I’ll be discussing the works of artist Oswald Hussein and how his work, though strong in its Indigenous roots, connects me to my faith and belief.

Oswald Hussein is a founding member of the Lokono Artist Group, a group of Indigenous artists whose pioneering work has led to a new movement of Indigenous art in Guyana and a solid foundation for the Moving Circle of Artists in Guyana. Oswald Hussein came from a rich cultural background of the Indigenous people who, while they engaged in basket, canoe and pot making, were never seen as sculptors. Hussein has become a model for a rich vein of Indigenous sculptors, winning the sculpture prizes in the National Visual Arts Competition with Massasekere in 1989, Wegelly in 1993, Communicate in 2014, and Silence in 2017.

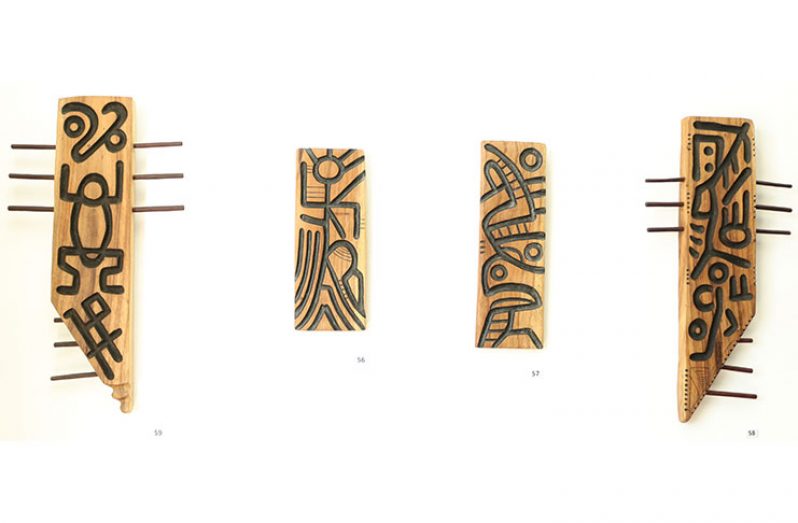

Indigenous rock paintings serve as the virtual window to the rich tradition. They contain clues to important social, economic, and spiritual insights about the life of the people. For the Indigenous people, however, these art forms are key to the religious tradition of their ancestors. As a sign of continuity, the Indigenous make an effort to reconstruct these images to preserve their tradition. This brings me to four interesting wood pieces entitled Rock Carving 1-4, currently mounted on the walls of Castellani House. They are in the entryway of the main hall in which the exhibition is being held. These pieces are replicas of Indigenous rock carving done on Saman wood. The fascinating thing about it is that I have no idea what they represent. I spent some time looking at it and pondering – what does this even mean? It wasn’t until a few days later while reading God’s great blessings devotional by Patricia Raybon, that I received a revelation from God about how I should view art.

“All art forms attempt to translate what is unseen into what is seen,” Painter Joel Sheesley states. Author Michael Card in his book Scribbling in the Sand: Christ and Creativity suggests that “the definition of content in art is very much like that New Testament definition of faith that calls faith `the substance of things hoped for. Art, especially as we engage in it with a redeemed vision, becomes an activity of faith, translating the “substance of things hoped for” with words, paint and other materials into the content and form of art.”

Card further explained that: “Whatever stops the world is art. Whatever makes the world pause and pay attention to something greater. Whatever shows the world’s busy people – so self-absorbed and angry with their self-ness – that their world is not the only world that existed. And so, they were liberated. And that, too, is art.” For Carl, his creativity is inspired by the creativity embodied in Christ. He uses the example of when Jesus interrupts a howling mob of Pharisees eager to stone to death the adulterous woman – by stooping down and scribbling in the sand with his fingers. Twice. To this day, Card writes, “We have not the slightest idea what it was Jesus twice scribbled in the sand. It was not the content that mattered but why he did it. Unexpected. Irritating. Creative.”

As I look at the images, I think of Hussein’s work and I can’t help but visualise the markings on the sand. His craftsmanship makes it appear as if the motifs were engraved with the simple stroke of one’s finger. His choice of the Saman wood because of its colour helps to create the contrast needed to appreciate the design of the motifs. So, even as you look at the works of our Indigenous people, don’t get consumed with the interpretation of the pieces rather focus on why they did it. If you are fortunate to hear the story behind the ‘madness’, that’s great. Understand this though – the Indigenous people create, as a means of preservation. And I must say, I’m loving this year’s theme: Maintaining traditional practices while promoting a green economy.”

.jpg)