I ALWAYS consider these articles to be more along the lines of ‘book recommendations,’ rather than ‘book reviews.’ I find that it’s more intimate to consider the writer/reader relationship in this way – as though my thoughts and feelings about culture and literature were flowing between myself and the artistic people, or people interested in the arts, who read my articles in the way that conversations between close friends swing back and forth, back and forth.

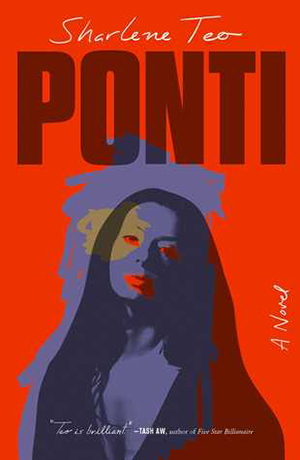

My recommendation today plays into these very ideas, as it is a novel that swings back and forth between three central characters. The work is called “Ponti,” written by London-based Singaporean writer, Sharlene Teo. The book glides between an ageing former movie-star, her clingy daughter, and her daughter’s wealthy best frenemy. The intimacy formed in the explorations of these women’s relationships is piercing, hot, and bright – quick as a bolt of lightning, the beautiful kind that you remember long after the storm, long after you have closed the book.

My recommendation today plays into these very ideas, as it is a novel that swings back and forth between three central characters. The work is called “Ponti,” written by London-based Singaporean writer, Sharlene Teo. The book glides between an ageing former movie-star, her clingy daughter, and her daughter’s wealthy best frenemy. The intimacy formed in the explorations of these women’s relationships is piercing, hot, and bright – quick as a bolt of lightning, the beautiful kind that you remember long after the storm, long after you have closed the book.

The novel starts off in 2003, with a teenage girl named Szu. She tells us, “Today marks my sixteenth year on this hot, horrible earth. I am stuck in school, standing with my palms pressed against a green wall. I am pressing so hard that my fingers ache. I am tethered to this wall by my own shame.” There are several things that I find beautiful in those opening lines. First off, is the author’s restraint.

The opening may appear (at the first glance) to be unshowy, mild and lacking in the bombastic outpouring of literary sentences that we are told to inculcate when crafting opening lines. However, from my perspective, the opening lines to Teo’s novel speak in the unassuming language that a wallflower-type high-schooler might use, which means the language is accurate – and accurate presentations of people, of types, need to be applauded.

The author’s restraint in the language used helps us to identify, to place, and to know the character of Szu. Secondly, the opening lines also allow the readers to place themselves perfectly in the shoes of the 16-year-old narrator. The words are so precise and precisely placed – “I am stuck in school, standing with palms pressed against a green wall” – that upon reading it for the first time my own high-school voice, depressed and apathetic, comes back to me, reminding me that as teenagers, we all did strange things – secret things, strange customs and rituals, that were ours alone.

Who, as a teenager, has not pressed their hand to something in a moment of sadness, anger, or confusion, and allowed the world to disappear behind you as you focused on a colour or a pattern or a symbol? Who here in Guyana has not referred to the world as “hot and horrible” at some point in their lives? Who has never been so scared that you feel pinioned – “tethered” – to a seat or a wall or a table or something else that you need to anchor yourself in a moment of need or weakness? Teo has perfectly replicated the teenage years – that dark time of friends who could be enemies, of wanting to achieve perfection, of wants and can’t haves – in the characters of Szu and her friend, Circe.

If Szu represents the awkwardness and pain of being a teenager, then Circe surely represents the years after – adulthood – when the repercussions of things done in youth yet finally catch up to us. Amisa (Szu’s cold, haughty mother), then, comes across as the ageing individual, and her story, by far, is the one that is most likely to resonate with Guyanese readers, particularly those of us who work in the arts.

Amisa grows up in the 60s in a poor Singaporean village that is easily reminiscent of the Guyanese countryside. Amisa is extraordinarily beautiful and uses this beauty to land a singular role as an evil force in a film. She is confident that she will become a star. She goes to the scarcely-attended premiere to see her first acting job on the big screen, and Teo’s prose is a cutting description, wincingly and painfully accurate, as she whittles down the horrors of being an artist, slicing away hopes and dreams to reveal something terrifying and dark and truthful.

Teo writes: “On the large screen, she [Amisa, as the beautiful, deadly spirit in the film] popped out from a cupboard. Hands extended over her head, cartoonish. Novita chuckled beside her, and at that moment, Amisa hated the girl. That big reveal had taken hours to shoot… How her back ached from stooping inside that mahogany cupboard, waiting to spring the doors open, to howl. She had boils and welts painted and glued down on her arms and legs.” This description of Amisa’s failure as an actress is balanced by all the hard work and energy she put into her performance – and it is a savage reminder of the reality of being an artist in a world that does not always appreciate everything that we do for it.

Nevertheless, Teo’s novel is not entirely devoid of hope, not when it comes to the characters or their feelings, their relationships, or their efforts. Even Amisa eventually achieves what she initially wanted, sort of, as her film becomes a cult classic – and what a film it is. Teo’s creation of a fake movie is so real and interesting and cool that I have never wanted to see a non-existent work of art more than I want to see Amisa’s film, with its South Asian horror elements and B-movie appeal. The film seems real, but sadly, it isn’t. Has anyone ever made a real movie based on a fake movie before? I’m telling you, there is merit to the idea.

An important aspect of “Ponti” that is certainly real, however, is the Singapore of the novel, a striking place, hot and filled with lies and hate and anger and flawed people and secrets and hope, and dreams, and love – much like another little tropical country I know.

“Ponti” makes for a fine read, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone looking for a challenging, melancholy, gorgeously-written novel.

.jpg)