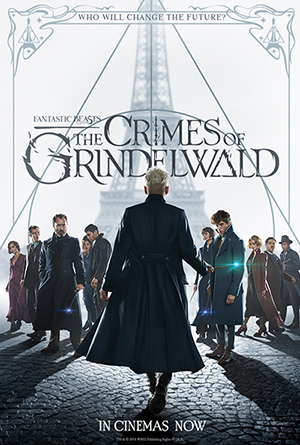

IT is difficult to believe that “Fantastic Beasts: Crimes of Grindelwald,” J.K.Rowling’s second entry into her ever-expanding Wizarding World, was written by the woman who taught an entire generation of children to love reading with her Harry Potter books.

Similarly, it is also difficult to believe that this film was directed by the man who brought us the last, and perhaps, the best Harry Potter movies in the original series. “Crimes of Grindelwald” is such a contradictory, hurried, pointless, mish-mash of muchness that it is sure to underwhelm many fans of the original series who were expecting something more acclaim-worthy. Not only does the film fail by being a lacklustre addition to the Harry Potter canon, but it also fails as a film by undermining the one rule of films: be entertaining.

To watch the movie is to be confronted with the sad fact that Hogwarts and the rest of the Wizarding World, in the hands of the wrong people with misplaced motives, can be dreadfully boring. There are some aspects of the film that are good, but like a baby sinking into the sea (an actual image from the film), these are all drowned out by the flaws that loom as large as the paper-thin characterisations that the film highlights.

To watch the movie is to be confronted with the sad fact that Hogwarts and the rest of the Wizarding World, in the hands of the wrong people with misplaced motives, can be dreadfully boring. There are some aspects of the film that are good, but like a baby sinking into the sea (an actual image from the film), these are all drowned out by the flaws that loom as large as the paper-thin characterisations that the film highlights.

There are several facets of commentary that can be gleaned from analysing various parts of the film, but the one that is most relevant right now, in my opinion, happens to be Rowling’s treatment of minorities in her work. There has already much talk about this throughout the years (see: Black Hermione, allegations of the cultural appropriation of Native American culture by Rowling, and the casting of Nagini in “Crimes of Grindelwald”), so for this article, I will only focus on “Crimes of Grindelwald” as it is the most recent expression of Rowling’s work in the media/pop culture/literary landscape.

The first type of minority that demands exploration is the sexual minority in “Crimes of Grindelwald.” The Harry Potter fandom erupted into a furor when Rowling announced, years ago, that Albus Dumbledore (the kind, brilliant headmaster of Hogwarts) was gay. This was revealed after literally no explicit evidence about his sexuality ever appeared in the books, and, logically, fans began to hope that Dumbledore’s queerness (particularly his love for his friend, and enemy, Gellert Grindelwald) would appear in “Crimes of Grindelwald.” Leading up to the release of the films, fans were assured that this movie would finally, after a long time, shed light on Dumbledore’s sexuality and finally give us the information we needed on Dumbledore and Grindelwald’s relationship.

It was to be an important move for Millenials who grew up on Harry Potter to see Dumbledore (portrayed in quite a good performance by Jude Law in the movie), one of the most powerful wizards of all-time and one of the Harry Potter series’ best known and bestloved characters, as a flaming homosexual. Needless to say, this did not come to pass in “Crimes of Grindelwald.” In fact, it came nowhere close to what fans expected to see.

All we got was an instance of Dumbledore saying that he and Grindelwald were “closer than brothers” and a scene of the two as young men, cutting their palms and pressing the blood together – like something out of a bad teen romance – and then holding hands. It lacked all the emotion, all the fire, all the intensity that was needed to highlight this relationship.

A simple kiss would have done the trick, but Rowling chose another route. “What is she scared of?” “Why doesn’t she want to make Dumbledore explicitly gay?” I have no idea. All I know is that this continuous putting off of any expression of Dumbledore’s queerness in the movies makes it extremely easy for critics to slam her work as being another example of queerbaiting in the media, another example of constantly hinting at the queerness of a character in order to rack up fans, engender promotion, or to stimulate interest, without actually giving manifest to the character’s queer nature in the film or book.

The second concept of “minority” that we need to look at in “Crimes of Grindelwald” has to do with race. First off, kudos to Rowling for including more people of colour in the second installment of this franchise. That’s definitely a good thing. However, there is still much more work to be done.

People were very upset when they found out that South Korean actress, Claudia Kim had been cast as Nagini, a character who is later permanently transformed into a snake, and made into a slave and vessel for Harry’s arch-nemesis, Lord Voldemort. The problem with this, as pointed out by Megan C. Hills, in a piece for “Marie Claire,” is that Nagini’s persona as being a non-verbal, submissive slave of a “dominant, white male” reeks of tropes associated with Asian stereotypes.

This analysis is apt and becomes more profound especially after one has seen the film. Nagini in the movie is relegated to a bare handful of lines, with very little to do besides befriend another character. Her presentation immediately seems to confirm the “non-verbal” aspect of things, given how little lines she has and how little of an impact she makes. Claudia Kim seems like a capable actress, and I hope for her sake, and the sake of her character, and the sake of the entire Harry Potter fandom, that in the upcoming movies, Rowling gives her more to do instead of simply keeping her on the sidelines as she waits for the moment to be permanently turned into Voldemort’s pet.

Next, in how the presentations of people of colour failed in “Crimes of Grindelwald,” we have the character of Leta Lestrange – played by Zoe Kravitz. The actress must be commended for being one of the few actors who was able to draw nuance while helping to develop her own character despite the sketchy draft she was given to work with. Truly, Kravitz is one of the rare aspects of the movie that I actually enjoyed. However, her character as a representation of a racial minority in the Harry Potter universe is flawed. Leta Lestrange is a child borne of a black woman (already married with a son of her own) who is cursed and controlled by a white man who forces this woman to become his wife, after which she becomes pregnant.

The woman dies giving birth to Leta. Kadeen Griffiths, in an article for “Bustle,” points out that “…a white man magically taking control of a black woman and then using that control, in part, to rape her is an uncomfortable slavery narrative…” Griffiths also points out how this narrative is then used in the film to portray Leta as the “tragic mulatto.” Why this slavery narrative was drawn without a full analysis of its role in the film by the filmmakers is unclear to me, and Leta, despite all her potential, eventually is reduced to nothing more than another attempt at including a person of colour, without all the necessary pain and hard work it takes to render her accurate and worthy of contribution in a positive manner to the discourse on race.

Of course, one can continue the analysis of other minority characters in the film. We can talk about the failings of Seraphina Picquery as a character, or of Queenie (my favourite character from the first film) – as a woman – being reduced to nothing more than an airheaded, lovelorn girl, or more about Dumbledore and his yet to be seen queerness. However, I have a feeling that the upcoming movies will provide much more to talk about, especially when it comes to the presentation of a subject as current and as important as minorities in film.

.jpg)