By Gibron Rahim

IT IS inevitable that cultures change with time. This is especially evident in multicultural societies, such as Guyana, where cultures interact with and influence each other. The fields of anthropology and archaeology are the key to keeping a record of how cultures have changed and will continue to change over time. It is for this reason that the University of Guyana’s Amerindian Research Unit is so vital.

Anthropology is the study of all human culture while archaeology is a subset of anthropology and is the study of the human past through the recovery and study of material culture. The Amerindian Research Unit (ARU) grew out of the Amerindian Languages Project. The Amerindian Languages Project (ALP) was founded by Guyanese linguist, Dr. Walter F. Edwards, in 1977, with a small grant from the University of Guyana’s research fund which was supplemented by a grant from the Upper Mazaruni Development Authority (UMDA) under its then director the late Desmond Hoyte. The main objective of the project was to provide dictionaries, grammars and cultural descriptions of as many of

Guyana’s nine tribes of Indigenous peoples as possible.

Though the ARU has seemingly been out of the public eye these last few years, the body has been involved in numerous ongoing projects. Louisa Daggers has been the ARU’s coordinator since 2014. She told the Pepperpot Magazine that the Unit has been collaborating with the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology to offer a field school. She related that the Denis Williams Archaeology Field School was started at the University of Guyana in 2007. “It’s a collaboration between Boise State University and the University of Guyana, and subsequently the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology.” Noting that the programme could not have been carried at UG due to financial constraints, she said that the museum took on a majority of its financing.

Later, the decision was taken to diversify the programme and make it more compact. “We

added an academic component to it where students did maybe two weeks of classroom sessions before going out into the field,” Daggers explained. This has provided students with much-needed background knowledge before they attempted any fieldwork. The ARU has undertaken all of the planning, liaising with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), logistics and classroom sessions. The ARU also supervises the field school in collaboration with Dr. Mark Plew of Boise State University. Dr. Plew has been the face of the field school since it was founded in 2007. “Our target has been University of Guyana students who we believe would like to have more exposure in the field,” said Daggers. The application process is rigorous and environmental science and history majors are among the usual applicants.

The field school also provides capacity building to the communities it works in, as well as for Guyana’s museums. As an example, Daggers noted that the Walter Roth Museum has an archaeological collection and shares its information. “We see [the school] as a means of strengthening their internal capacity,” she said.

In addition to the Denis Williams Archaeology Field School, the ARU offers a service course which is a collaborative effort between five faculties at UG. The course acts as an introduction to anthropology and an introduction to the Indigenous Peoples’ of Guyana.

There is also a relatively new associate degree programme in anthropology being offered. “We’ve been teaching courses out of that,” Daggers related. She noted that the current cohort of students while numbering only five, is a good start.

Over the last few years, the ARU has been co-publishing the Archaeology and Anthropology Journal in collaboration with Boise State University. The publication is the journal of the Walter Roth Museum and was started by the late Dr. Denis Williams. Daggers noted that the peer-reviewed journal is the only one of its kind that is published in the English language on the South American continent. “Because of the limited capacity of the museum to produce this journal, we decided that we’re going to do it for them,” she explained. She noted that the journal was made open access to celebrate Guyana’s Golden Jubilee and to boost readership and referencing.

The ARU also publishes Monographs in Archaeology. That publication came about as a result of the field school and contains the records of the excavations conducted in the field with the students and the results. Those materials were once part of the Archaeology and Anthropology Journal, but, after the Unit realised the relevance of having a separate publication the decision was made to start printing the monograph annually.

True to its name, the ARU has also been conducting field research. Daggers acknowledged that the ARU’s focus has largely been on archaeology, since that is the staff’s area of expertise. “But where we can we also do ethnographic work – collecting cultural, socioeconomic data,” she noted. She related that the unit has been undertaking preliminary surveys on sites before excavation takes place as well as the survey and documentation of the socioeconomic conditions of Indigenous communities. The ARU also sometimes undertakes special exercises, as was done a few years ago in the village of Aishalton, when the Unit examined a management plan for archaeological sites.

The Unit has been working on developing a management plan for Aishalton by documentation of “everything that’s existing”. “That’s one of the largest petroglyph complexes that we have in Guyana,” Daggers explained. “The initial aim was to have it gazetted through the National Trust and possibly have it as a World Heritage Site once we meet the necessary requirements.” World Heritage Site status, she pointed out, would require a lot of funding for conservation and also training within the community. For now, the ARU is focusing on documentation and publications on the site. The unit is doing the same with the village of Shea which is home to a rock shelter and pictograms. “And we’ve documented sites that were known but never documented because people couldn’t find them.” More recently the ARU has been looking at culture and the influence of coastlanders on economic development in the Rupununi.

The unit received an archaeology grant from the World Bank in 2016. The purpose of the grant was to fund a research study to ascertain whether prehistoric populations were contributing to climate change, or how their practices stabilised climate change. The project was a success. “It was nicely accepted across the hemisphere,” Daggers confirmed. The ARU conducted numerous talks stemming out of the project and parts of the research were published in the Latin America Antiquity Journal this year. Additionally, “We have been invited by one of the leading U.S. archaeology associations to present our findings next year,” she related. She noted that the ARU is attempting to move toward using more technologically advanced archaeology methods to keep pace with the outside academic arena.

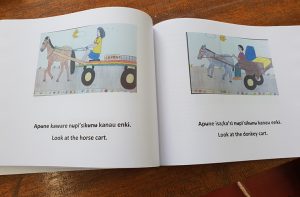

Jennifer Wishart, a part-time staffer at the ARU and former curator of the Walter Roth Museum, handles numerous projects related to the Indigenous languages. She noted that the upcoming year 2019 has been declared the International Year of Indigenous Languages by the United Nations. She pointed out that, prior to that announcement an official at the Ministry of Education had approached the ARU with regard to translating nursery school level texts into four of Guyana’s Indigenous languages for hinterland schools. There was some delay as the Unit tried to plan logistically.

Then, Akawaio language specialist, Rita Hunter of Jawalla, stepped in to help by translating the 16 texts into the Akawaio language. Adrian Gomes, Benita Roberts and Ovid Williams then translated the English text into Wapishana, Macushi and Patamona, respectively. Wishart was responsible for typing up all of the translations which were then handed over to the Ministry of Education. She noted that the ministry has taken a step further and decided that it would like to have the books made into animations.

Daggers emphasised that the ARU’s main purpose still remains research. “We’ve recognised that we cannot do everything, we don’t have the resources to reach every facet of anthropology and all of our people,” she said, “but we advocate for research and in doing that we support researchers.” Part of this involves facilitating public talks, including recent talks given by Dr. Plew and Dr. Mariapia Bevilacqua. “It’s something that we want to do a lot more next year because next year is the International Year of Indigenous Languages,” she said.

The work of the Amerindian Research Unit is necessary according to Daggers. “It’s actually critical research because culture changes, it’s dynamic, nothing is static,” she said. “Our role is fundamentally documenting things the way they are.” The unit also plays a vital role in the conservation of artefacts. “It’s really important for us to document culture and salvage our archaeological heritage because these are natural treasures and they’re cultural patrimony – they belong to the people,” Daggers stated emphatically. “They constitute cultural identity and the moment those things are lost, then we start questioning who we are and where we belong.”

.jpg)