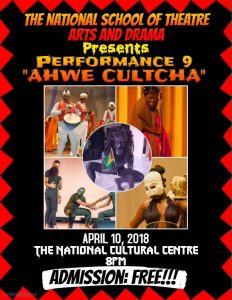

THE National School of Theatre Arts and Drama (NSTAD) is hosting its ninth performance. It is five minutes to show-time and they are not yet ready. I sit in a corner and smirk, realising that we will be starting late. Being backstage, but not being in the production, I realise, sometimes feels like what sitting in the eye of a storm must feel like. I myself am breathing deeply, sitting still, waiting for the time I am needed. However, all around me, there is a frenzy of activity, trying to outrace the clock that has already run past the finish line.

I see actors dragging set pieces on to the stage. Men and women, beads of sweat trickling down their dark skin, as the lights go out backstage and a semi-darkness floods the stage. The thick black curtain hides everyone from the audience. The eyes of the audience are only meant to view perfection. They should not see the set pieces being dragged into position, the props placed at strategic points on the stage, the half-naked actors fumbling to get into their costumes lined with sequins or bolts of coloured cloth or paint. The audience, regardless of the fact that there is not a great number of them present, or perhaps because of this fact, is our most precious asset, and the thespians give to them their best. How they arrive at their best is not important to the audience.

They say they are ready, and the National Anthem plays. People are introduced, speeches are made. Then it is time. The first play, tying into the night’s theme of culture, is based on Wordsworth McAndrew’s famous poem, “Ole Higue.” The voice of the narrator is too low and I hurry to tell the Stage Manager to lower the microphones some more. I say the words to him and he says it to the walkie-talkie and the machine transfers it to the Sound Technician, and then the microphones come down some more. The girls awkwardly change their costumes on stage – rather than giving us the neat, ritualistic flow that is required. But I know the audience enjoyed the beating of the ole higue. The licks come quick, sharp and real-looking. Applause.

We wait again as the cast members get into costumes for “Baccoo”, written by Sonia Yarde. This play has live drumming and it adds to the whimsical folklore-like qualities of the performance. The baccoos are more human than baccoo, in voice and movement, but the costuming manages to sell the act. I wonder what the audience felt when they saw those creatures from Guyanese culture strolling and dancing on the stage? Was it nostalgia, sorrow, joy? Everyone knows folklore is dying. Who is doing anything about it? The National School of Theatre Arts and Drama for sure, as seen in the way they built their entire production around this theme. But who was there to see it? Who was there in the audience to help preserve folklore at least in local theatre? Besides everyone attached to the play – there were only two handfuls of audience members. What are Guyanese theatre-goers really looking for these days? I stand at the peephole looking out at the empty seats and I think of the students behind me, rolling out the sets they designed, painting on the face makeup they bought and rehearsing the lines for scripts that they had been practising for weeks. My heart grows heavy. Applause.

“Sirens”, written by Tashandra Inniss gives the night its international flavour, as sirens are not really native to the Caribbean. The actors lift their boat on to the stage and began the story of a doomed group of sailors who ignore the warnings of their captain and are lured to their deaths by the beautiful sirens. The sirens tear their masks away from their faces and leap on to the men – but the act is not sexual as the sailors expected. This is the moment when the sirens bare their fangs and tear into the men. The captain hurries away, and the sirens bested at their own game by the one soul that slips through their fingers, kill themselves. Rich, intense stuff – with very little people there to enjoy it. Applause. Intermission.

African drumming plays as “Celebration of Life” begins. It showcases the birth of an African princess in a tribal village setting. The dance pieces of rhythmically, beautifully choreographed and the girls are decked out in African wear that seems lifted directly all the way from Africa itself. Everything is going well until there is silence on the stage. The actors are not doing anything. Then the realisation hits me, someone has forgotten their lines! Everyone waits with bated breaths, and then, finally, it comes. I let out a sigh of relief as I watch the performance from the wings. It ends on an anti-climactic note, but at least the dancing and costume were memorable.

They need time to change into their elaborate saris and jewellery for “Maticore” – the last play of the night written by Steven Seepersaud. There is dance and Tassa drumming and cross-dressing in this one. The Creole spoken is thick and raw, and true to some sections of the rural Indian communities. The female family and friends of the bride dance in suggestive/sexual ways, teaching her what she must do on her wedding night. How scandalous and wonderful it was, to have a hidden part of the Hindu wedding tradition exposed for the entire world to see. It reminded me a bit of the African queh-queh tradition. Similarities exposed. The entire play was as strange as seeing folklore on the stage to see a section from the Indian experience in a play. It is indeed a rare phenomenon to associate Indian culture with theatre in Guyana, despite the many influences of the genre that has helped to shape what is now known as Caribbean theatre. The cross-dressers are revealed to be women, and hilarity takes over.

.jpg)