EVERY family has secrets. In Guyana, there is a theme of the forbidden that is shot through the spine of this country and the many buried conversations regarding topical issues such as crime, sex, race, and religion that we refuse to address. So it is easy to understand how the Guyanese society is one that swells with secrets, ripening until, like boils, they rupture one by one.

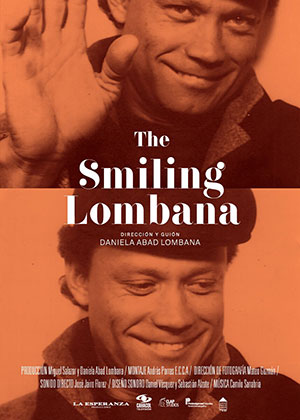

This is one way in which Guyanese may be able to relate to the “The Smiling Lombana”, Daniela Abad’s highly personal documentary in which the Colombian director relates the true story of herself, her mother and aunts, her grandmother and, most significantly, the story of her grandfather, the Colombian sculptor, Tito Lombano, and the secret he kept from his family.

This film is one that can be useful in the effort to twist the gaze of Guyanese audiences away from the silver screens of Hollywood and onto movies that celebrate and represent the experiences of the Caribbean and South America, simply because of its familiarity in the theme of family secrets, which thrive in our society. “The Smiling Lombana” was the opening film at the 58th International Cartagena Film Festival, which was held in Cartagena, Colombia and presented some of the finest contemporary works of Latin American and World Cinema.

The documentary is narrated by the director herself, which, perhaps, might be considered one of the film’s few flaws, with the insertion of Abad into the story she is telling. Here is an art form in which the artist is inserting herself in a more blatant rather than, unlike most other artists, in a subtle manner. There might be a significant lesson in voice in storytelling and art here, as Abad, like her aunt and grandmother, is related to the enigmatic man at the centre of it all.

Abad is as much part of the story as any of the others – it is the story of her grandfather. Her voice then becomes the contemporary, Millenial voice, joined with a chorus of women who have all been affected by Tito, the man known as the Smiling Lombana. It makes sense that in her own artistic work, the director would include herself since it not only stems from her, but it also tells her story about the personal, about her family, and about herself. The story, the artwork, is as much Tito Lombano’s as it is hers. Perhaps, this is a reminder to all artists that all stories we tell through our art are our own stories in some way, regardless of how removed it might seem from our immediate environment.

From a technical standpoint, the “The Smiling Lombana” is sound – utilising a myriad of voiceovers, pictures, old home video footage and an assorted array or images to shape the mixed life of Tito Lombano. Born poor and gifted, he relied on his skills as a sculptor to make his way to Europe where he met the woman who was to become his wife. The theme of Tito’s artistic skills is a resounding focal point in the documentary, represented in the way his works are alluded, but also in the way the idea of art being a creation, shaped by an artist, might be indicative of the ways in which Tito also shaped himself and his life, which, like itself was only a reflection of the truth or what was real.

Tito’s popular sculpture, The Old Shoes, larger than people, with one of the shoes lying on its side of the other half which remains upright, in particular, has a similar history of ruin and renewal, like Tito, which is why it makes an appearance in the documentary.

As a work of art, the documentary succeeds in telling the story of a man without the man himself ever appearing, as he died before Abad began the film.

It is an exercise in how to create a character and the director does it in such a way that we get a thorough understanding of who Tito was as a person. Using interviews, research, symbolic imagery, an excellent soundtrack, and stories she has heard from her family all her life, Abad has managed to craft her grandfather back to life again. He captures the audience’s attention with his good looks and charm.

He makes us blush with the lightness with which he dances or exercises. His skills as a sculptor are remarkable and there is a general sense of charm that emanates from every image we see of him. All of the women, even wife whom he has betrayed, still betray some affection for the man which shows more than anything else that love – like art – which fuels art, often endures and manifests itself in new and unexpected ways, in new and unconventional mediums.

.jpg)