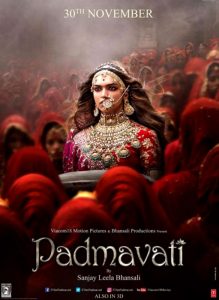

Image via: Deccan

Chronicle

THIS week I write about Padmaavat again simply because I cannot get it out of my mind. I have always been a fan of Bhansali’s work and while Padmaavat is not a perfect film (with the outrage against the regressive depiction of women, in particular, being mostly justified), there is enough to hold our interest in the way it shamelessly flaunts its excessive visual beauty, its solid performances, and its entrancing music.

The film starts off with the beautiful Princess Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) hunting in the forests of Singhal, where she accidentally shoots the noble Rajput king, Maharwal Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor) of Chittor, who later becomes her husband. In these opening scenes alone, Bhansali reminds us that he has an extremely aesthetic directing style and a flair for things visual. The forest is haunting, with giant trees and vines, and an atmosphere within it that it almost seems alien, surreal, too mythic to be a forest on earth – as if it could be the perfect setting for the home of the demons who lived in the stories of the gods that we know from Hindu myths. It is a strange and beautiful thing – this forest – and I spend all of this time talking about it because the forest, richly rendered and layered in mystery and life, was the first sign that, for someone who is moved by aesthetics and imagery, this was going to be a pretty good film. If Bollywood ever does a movie based on the Ramayana (and they should), Bhansali’s vision of the forest would be perfect to represent the haunted, demon-filled jungles that Rama, Sita, and Lakshman spend their exile in.

While on the story of Rama, it is worth mentioning that Bhansali’s film draws an interesting parallel with the holy text in terms of plot: Rama’s wife is abducted by the demon-king, Raavan; while in the movie, the villain, Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh), a Muslim ruler from another kingdom, driven by an insatiable appetite for power and convinced that Padmavati, as the most beautiful woman, belongs to him, lays siege to Chittor and sets about trying to conquer the kingdom so he can get to Padmavati. It is an epic tale, told in blood and fire, matched only in tone and spirit by the performances of the actors who are all in fine form, contributing to the splendor and general air of doomed sumptuousness that pervades the film, as if they themselves, like the sands in the deserts outside Chittor, or like the era in which the film itself is set, will blow away in the blink of an eye, carrying with them their teary-eyes, their broken hearts, their dreams, and the beautiful story they are all a part of.

Deepika Padukone in the lead role is astounding to behold. She emotes so much through her eyes and manages to fill the character of Padmavati with such wisdom, strength and strategy (Padmavati is the one who comes up with most the ideas that could have led to the defeat of Alauddin) that even when the character commits “jauhar” (mass self-immolation) along with the rest of the Rajput women at Chittor, one can’t help but fall apart at the loss of a soul as brave and intelligent and determined as Padmavati. It is quite easy for modern people to judge her actions and to label the choice of all of the women of the kingdom to kill themselves in a fire as representative of the patriarchal system under which they lived, and while patriarchy definitely existed and operated then as it does now, we must ask ourselves: what other choice did Padmavati and the women have? Perhaps they should have waited for death to come to them as their husbands, brothers, sons all died on the battlefield? Perhaps they should have awaited the arrival of Alauddin and his forces who would no doubt set about raping and enslaving the women and pillaging the city? Grief, in my opinion, and not so much honour, was the driving force behind Padmavati’s choice to kill herself. Today it might be justifiable to condemn a woman killing herself because of honour, as that definitely reeks of patriarchal ideals.

However, my interpretation of Padmavati’s final act of courage and defiance is that she refused to succumb to rape, she refused to go without a fight, she refused to become a victim. Padmavati made her own choices and committed suicide not to save her honour, but to not live a life without her husband – note how she takes the scarf stained with his palm-prints with her into the fire – and that begs the question: who does not know of such heartache? Who does not know what it is like to lose someone that it hurts so much and in your heart you know you cannot continue with them? This is how I related to Padmavati, and while I absolutely do not condone “jauhar”, I do understand the psychological effect of losing someone you love, and the possible consequences of that.

Shahid Kapoor as Padmavati’s husband is striking as a king and he wears the naïve nobility well. His scenes with Padukone are particularly sensitive and sensual. He really helps to convey the deep love the characters have for each other. Ranveer Singh is wild and ferocious in his role, bringing the required intensity, insanity and power that were necessary for his transformation into the delusional emperor. Kudos to him also for accepting a role that involved such a high level (for Bollywood) of homoeroticism alongside the servant (Jim Sarbh), in a relationship that had echoes of Alexander the Great (with whom Alauddin compares himself to) and his lover, Hephaestion. It is awful that the homosexual angle is played out among villains, but nevertheless, such visibility onscreen is new for Bollywood. (Side note: did anyone else see some phallic symbolism in the torch that the two men played around with?) The last performance that needs a special commendation is that of Aditi Rao Hydari as Mehrunisa, the wife of Alauddin who brings searing condemnation and terrible vulnerability to her performance. She plays the tragic character so well that even when Padmavati goes into the flames and the film is over, you come away and you sometimes still think of Mehrunisa.

The final scenes leading up to the “jauhar” are among the most beautiful, best-directed scenes from a Bollywood film that I have seen in a long, long time. Bhansali uses the outrageously gorgeous costumes and jewellery that are littered throughout the film, as well as the sorrowful, majestic background score, to firmly place us at the scene of the “jauhar” where with a kind of precision and delicacy, complete with slow-motion shots, the angry faces of the women all clad in red and flinging embers at Alauddin, screaming as they hold their children and rush to the pyre, as radiant Padmavati leads them, as they shut the gates one final time against Alauddin and his men, there is a tension and grief that is palpable and alive – only succumbing as Padmavati steps into the flames and we see the look of horror and misery on Alauddin’s face when he realises that despite everything that he has done, everything that has happened so far, he has never – and will never – set eyes on the beautiful Padmavati. She steps into the flames, and he knows that everything he has done to get to her has been in vain. This irony is what sustains you, what keeps you whole and prevents you from falling apart, as the final credits of the film start rolling.

.jpg)