Writer Peter Jailall helping to build Guyanese culture, identity

By Ravena Gildharie

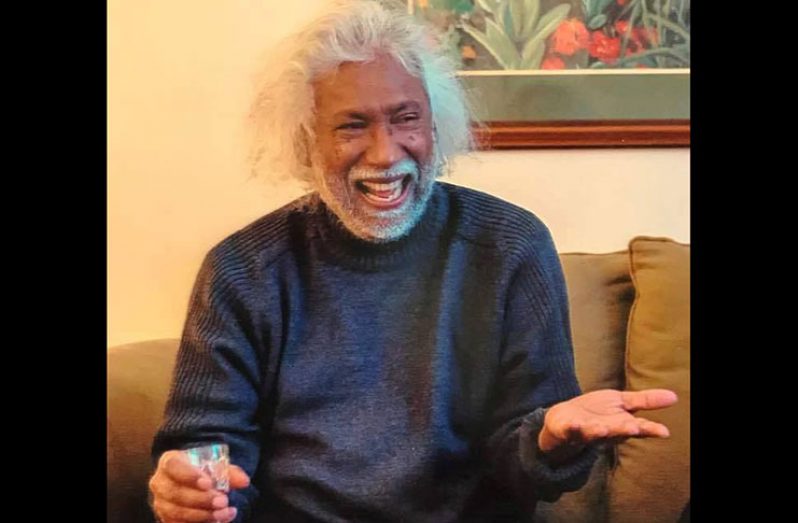

EASILY identified as one of the Caribbean’s most prestigious writers and poets with several successful publications to his name, Peter Jailall is a proud Guyanese, influenced by his rural upbringing along the East Coast of Demerara. Guided by fond memories of swimming in canals, picking fruits in the guava bush and playing ‘pitching marbles’, Jailall uses his

experiences of nature, unity and hospitality to create masterpieces of literature, adding life to the Guyanese culture and identity.

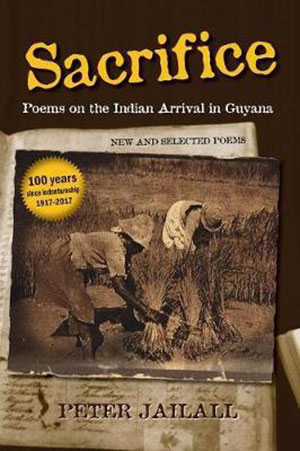

It is no wonder that many of his poems are decorated with colourful use of deep Creolese, and he remains an ardent advocate for its use as a form of language, unique to Guyanese, and which he believes is a powerful mode of expression that can be utilised in schools as a method to teach standard English. His published books include This Healing Place (1993), Yet Another Home (1997), Sacrifice and When September Comes (2003).

Jailall currently resides in Mississauga, Canada, with his wife and two sons. He was born in Guyana and attained his early education here. He graduated from the Government Training College for Teachers in Guyana in 1965 and has been an educator for 52 years. After he retired from full-time teaching in Canada, he has returned periodically to Guyana to teach children and train teachers as a member of the Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO) team. He continues to write and read poetry in Canadian schools as a member of The League of Canadian Poets.

“Teaching for me has been rewarding and satisfying,” Jailall told the Pepperpot Magazine, adding, “it has been also an important aspect of nation-building and character formation. My main achievement as a teacher is the satisfaction I experience in observing children’s joyful faces as they engage in the learning process. Also, the trust and positive relationships I have built with my students over the years give me a feeling of accomplishment.”

As a young man growing up in Guyana, Jailall was inspired to become a teacher by role models such as Miss Ainsworth, Miss Perry, Miss Fraser and Miss Abrams who taught him at the Ann’s Grove R.C. school. At the teachers’ training college, he gained a deep admiration for Fitty Miller, Joyce Trotman, Sam Small Archie Moore and Blanche Duke.

“Our teachers were like our second parents,” says Jailall, who grew up in what he termed the ‘ABCD villages’ along the East Coast of Demerara, as he refers to the Ann’s Grove, Bee

Hive, Clonbrook and Dochfour villages.

“As villagers, we cared for each other. We shared fruits and vegetables, swapped stories and broke bread together. We talked, we laughed and we cried together. We were family…The children in the ABCD villages belonged to all the elders. We were expected to attend school regularly and punctually. No child dared curse before an elder,” the poet said.

Life in rural Guyana

Jailall’s father was a farmer who grew rice, citrus and ground provisions and taught his son to love nature and to till the soil.

“I grew my own kitchen garden,” the now achieved poet boasts, as he recalled his days watering the plants, feeding the fowls and fetching water before attending school in the mornings.

“I read books and completed my homework before bedtime. Our parents and grandparents told us bedtime stories. We did not have television and cellphones in those days. We made our own toys, such as bats from coconut branches and marbles from ‘awara’ seeds which we scraped with our sharp white teeth,” he continued.

“We were a happy bunch of children from different racial, religious and class groups. We were friends who played, ate and slept at each others’ homes,” Jailall highlighted, proud of his Guyanese identity.

He has been returning to Guyana since 1985 and enjoyed teaching in many areas such as Mabaruma, Bartica, Santa Rosa, Mahdia, Shell Beach, Anna Regina, Leguan, Demerara and Berbice. He listens attentively to the dialects and speech patterns of all the children he taught and used the Creolese that they spoke to teach them standard English.

At Tagore Memorial High in Berbice, Jailall encouraged students to write freely in their own language, and he was impressed by the students’ ability to creatively express themselves with Creolese.

“If only their teachers and school administrators would refrain from categorising the Guyanese Creole as a debased form of English, their language skills could improve,” Jailall observed.

He is mostly recognised as an Indo-Caribbean writer and poet, and while he says he is proud of his Indian heritage, Jailall acknowledges himself first and foremost as a Guyanese writer. He also feels that there are many young writers in Guyana who need mentors and opportunities to get their work published.

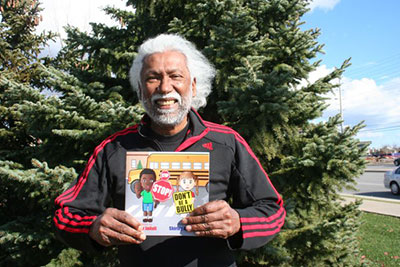

Jailall’s latest publication is entitled ‘STOP! STOP! Don’t Be A BULLY’, a book that has been well received in Canadian schools. He is currently collaborating with another famed Guyanese writer, Ian MacDonald, on a poetry book titled ‘Guyanese People.’

“I write for my own survival. Writing for me is therapeutic. I write to change the world and make it a better place,” Jailall said.

.jpg)