-The impact of crime on the individual, the community, the society

-Taking a look from the flip-side of the coin

By M Margaret Burke

Last week featured two areas: white collar crime, as well as domestic violence as a crime,

both of which impacts poverty in very direct ways in the society. Mr. Andrew Hicks detailed how these types of crimes can affect society in general and subsequent can be viewed a predictors of poverty.

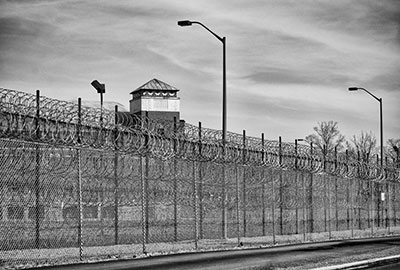

Crime and the criminal justice system

Mr. Hicks states, “Even without moving to the investigation of causation; even at the point where we can accept that there is a positive correlation, there is clear evidence in this correlative relationship that crime significantly impacts poverty.

“But it also means that if we have to spend more money in procuring weaponry; if we have to spend more money to address the effectiveness of the criminal justice system; which means having more magistrates and judges available to dispense with cases; which means having more prison space available to house larger numbers of perpetrators; which means investing in newer and more relevant forms of rehabilitation – what in fact we are seeing is that there is a social cost to crime, and the social dimension to crime is that which translates into an economic dimension or an economic cost,” he said.

Mr. Hicks, who has practiced extensively in areas of youth work, also served as a Peer Educator and Family Health Counsellor, and has focused on Criminology and the Criminal Justice for his PhD. The gentleman has concentrated much of his academic abilities in the expanse of drug use and mental health, peer influence, family relations on criminogenic behaviour and more.

Flight of human capital

Mr. Hicks noted that with the increase of any economic resources to fight crime would mean that at the distributive level there will be contractions in terms of how the nation benefit… “If government has to find larger sums of its economic pie to fight crime, then it means that less is available to pay our nurses, to pay our teachers, to pay our doctors, our engineers…and since these people will ultimately want to be paid market value of their salaries then this can contribute to a flight of human capital and so a nation that is loosing its human resources is a nation that is obviously prone to poverty.”

He pointed out that even when viewing crime through the traditional lens, merely looking at crime as the kind of criminal activities such as murder, manslaughter, robberies and such like; those criminal activities that are captured under the Unified Crime Statistics/Unified Crimes Index, what we would actually see, he said, is that very often the economic giants interested in investing their money, tend to look for societies where at minimum there is going to be some returns on their investment. He therefore posited the view that for a country to be able to attract good investment, it is believed that crime must be at a low level.

“You will never be able to rid the society to all forms of crime, but we must be able to manage crime to the point where there are some basic guarantees that the society can be safe,” he offered.

“Because if you have a consistent increase in robberies, gun crimes, murders and such like, that in itself becomes a disincentive to potential investors; it becomes a distraction to investors; and your investors, whether it be foreign or

local tend to decide that crime is intolerable and in the circumstances you may find that a nation that is saturated by crime can in fact, not only experience the flight of human capital, but also the flight of economic capital because businesses are likely to close and move to places where they feel they have a safer socio-economic environment,” Mr. Hicks said.

Socio-economic maladies

Mr. Hick explained that once the aforesaid becomes a reality, then this may result in the reduction of economic opportunities, for example employment opportunities, loss of income for families and obviously a loss of income could result in a reduction of the quality of life.

He went on to say that once persons experience those kinds of disruptions, they may then become vulnerable to other forms of crime such as drunkenness, substance abuse, alcoholic, and the like. This in itself, he noted, could result in ‘victims’ who become part of the lesser productive sections of the population and therefore their productive capacities become restricted, reduced and in the circumstances they cannot meaningfully contribute to the economic growth and development of the society, and in fact of themselves, their families and the larger society as a whole.

“My argument is that if you have a reduction in economic performances of the business sector that leads to a contraction of the industry as a result of increasing violence and crime within the society, then that may ultimately trickle down to a loss of employment, and the loss of employment may also correspond to a loss of social stability and that would inhibit the quality of human capital…We know the impact of substance abuse, whether we are talking about alcohol or about cocaine; the effects are in fact debilitating – there is an abundance of evidence to support that. So clearly and undoubtedly, crime contributes to poverty.”

Deter, incapacitate, rehabilitate

“In criminal justice a key function of punishment is to deter, to incapacitate and to rehabilitate. Unfortunately, in Guyana, the wider Caribbean, and elsewhere globally, what we’ve seen is that our prisons have not been very effective in terms of treating with these three goals. What we have seen is that, the prison, as a form of punishment is best at incapacitating, but neither does it deter, nor does it effectively rehabilitate.

The prison should be seen as a symbol of confinement, but correction

“And because there are problems that are associated with the kinds of interventions, the kinds of resources that we permit to deal with the issue of rehabilitation is often insufficient. What we find is that many of our inmates re-enter society after they are released from prison but they are not re-integrated into society, because they come from the prison lacking the necessary skills and competencies which will help prevent them from being induced from re-entering criminal activities,” he said.

He therefore stressed the need for attention to be paid to the kinds of rehabilitative interventional work that are being done in the prisons, stating that there is certainly need to have additional resources to treat with the whole issue of rehabilitation.

“It is not to say that it is impossible to rehabilitate; it is not impossible, but the State and the Community, as well as the private sector has to find a functional partnership that will allow for the amalgamation of resources so that we can have the maximum inputs at the best of outcomes…thus having an inmate, who upon his release returns to society as someone who has very sharp competencies and is someone who can actually be reintegrated into the society, the sociologist said.” mercilinburke2017@gmail.com

.jpg)