-says no violation of sovereignty of people

-no need for referendum

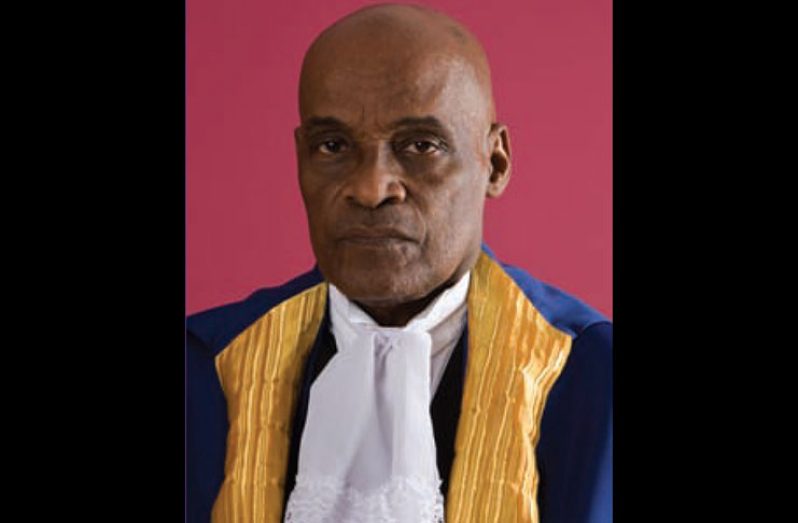

RETIRED Judge of the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), Professor Duke Pollard, has disagreed with the ruling of the Appeal Court and High Court in the third-term case, saying that Act No. 17 of 2000 does not offend or infect either Article 1 or Article 9 of our Constitution, which speaks to sovereignty of the people and that it is in full compliance with the provisions of the proviso of Article 164 of this instrument.

“Consequently, its validity or constitutionality does not depend on the favourable outcome of a referendum as posited by the aforementioned learned judges of the Guyana Supreme Court,” Justice Pollard declared. Observers say Pollard’s comments would be seen as sound and credible, having served as a judge on the CCJ panel for five years between 2005-2010.

The Court of Appeal by a 2-1 majority on February 22, upheld Justice Ian Chang’s High Court ruling back in 2015 that the presidential term limit is unconstitutional and void. Now retired Chancellor of the Judiciary (ag) Carl Singh, and Justice BS Roy upheld Chang’s ruling, while the then Chief Justice (ag) Yonette Cummings-Edwards disagreed. Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs, Basil Williams, has since indicated that government will file an appeal to the CCJ.

The original court action was brought by the still unknown Cedrick Richardson of South Ruimveldt, who many believe was used by Opposition Leader, Bharrat Jagdeo, who from all appearances is seeking a third term as president.

Justice Singh in delivering his decision had said that laws which in effect will prevent citizens from their Constitutional right to freely elect someone of their choice are unconstitutional. “In my view, the critical question which must be determined in this appeal is whether by altering Article 90 of the Constitution, Act No17 of 2000 also alters Articles 1 and 9 of the Constitution. It would be important to closely examine whether any of the core features of Articles 1 and 9 would be affected by Act No.17 of 2000.”

He noted that the provisions of Articles 1 and 9 of the Constitution, which speak to sovereignty of the people, ought not to be “lightly regarded” as they are deeply entrenched and provide substantive protection to the people of this country.

Careful analysis

However, in a letter to the editor of this newspaper, Justice Pollard said that careful analysis of the decision of Chang does appear that he reached his determination in the case by a finding that Act No. 17 of 2001 was not exempted from the requirement of a referendum to establish validity by the proviso in Article 164 of our Constitution. Chang had submitted that: “Since the alterations effected by Act No. 17 of 2000 to Article 90 also dilute and diminish democratic sovereignty (whatever that may mean) under Articles 1 & 9, the holding of a referendum was required to achieve legal validity and efficacy. None was held.”

Justice Pollard observed that Justices Singh and BS Roy had also concurred in the finding of Chang, saying that: “The legislatures under the Caribbean constitutions although extremely important, cannot, as Parliament can in the United Kingdom, claim superiority over the other two branches of government. Caribbean Parliaments are not at liberty to legislate whatever or however they see fit without having regard to the limits enshrined in the Constitution which ultimately have to be construed and guarded by the judiciary.”

Justice Pollard said in his letter that in effect, given the role of the judiciary as guardian of the constitution, this intractable issue appears to resolve itself into the aspirational concept of judicial supremacy, notwithstanding the expressed provisions in the Constitution designating this instrument as the supreme law. He said concerning the construction to be applied to “democratic” in Article 1 of our Constitution, Chang determined it to mean the disaggregated, discrete rights of the electorate including the right to elect the President and which in his submission could not be diminished nor diluted without a referendum. “In concurring in this opinion, the Honourable Chancellor (Acting) determined that “[t]he constitutional elements of sovereignty and democracy are not issues the Court can likely ignore. These are matters that touch the constitutional entitlements of our people. The Court must be prepared, and indeed it is the duty of the Court to ensure that the constitutional entitlements of the people are not eroded. A restrictive interpretation of the concepts of sovereignty and democracy, limiting them as being attributes of the state, without reference to the people goes against the grain of the approach to constitutional interpretation advocated by jurists in the Region and to which I referred earlier in my judgment.”

Exponent of constitutional interpretation

However, Justice Pollard quoted Francis Bennion, a leading exponent of constitutional interpretation in the international legal fraternity, who said that: “A statutory term is recognised by its associated words. The Latin maxim noscitur a sociis states this contextual principle, whereby a word or phrase is not to be construed as if it stood alone, but in the light of its surroundings. While of general application and validity, the maxim has given rise to particular precepts such as the ejusdem generis principle and the rank principle.” (Francis Bennion, Statutory Interpretation, 4th Edition, at p. 1049)

Undoubtedly, Justice Pollard said the constitution is a statute of inordinately peculiar significance and as determined in the celebrated case of Collymore v Attorney General: “No one, not even Parliament can disobey the constitution with impunity. The constitution is therefore the ultimate source of power and authority.” (R. M. Belle Antoine, Commonwealth Caribbean Law & Legal Systems, at p. 98) And in the authoritative submission of the internationally recognised Durga Basu, where the constitution has definitively, decisively and conclusively determined an issue, curial intervention is not to be entertained.”

The retired CCJ judge said in his respectful submission the construction applied by Justice Singh to the term “democratic” in Article 1 is “materially dysfunctional and egregiously flawed, if only by reason of the generally accepted rule of statutory interpretation enunciated by Francis Bennion above and encapsulated in the maxim noscitur a sociis.” Pollard argued that this maxim has given rise to particular precepts such as the ejusdem generis principle and the rank principle, which he said has been abolished. “However, what is important to bear in mind for present purposes is that the abolition of this derivative principle leaves essentially unimpaired the original principle of statutory interpretation from which it is derived.

“In the ultimate analysis, therefore, it follows as a matter of ineluctable inference that the term “democratic” must be construed in the same manner like the surrounding terms “indivisible”, “secular” and “sovereign,” all of which speak undeniably to a unified political entity in diametrical opposition to the Honourable Chancellor’s (Acting) concept of “constitutional entitlements of the people” which are not to be eroded and must be construed to comprehend, among other things, the right of electors to elect a President. But, needless to say, this interpretation of “democratic” must be seen to accommodate a construction that patently goes against the generally accepted construction in the international legal fraternity and enunciated by Francis Bennion. And in the premises, the interpretation of choice is between that of the Honourable Carl Singh, the Honourable Chief Justice Chang (Acting) and the leading authoritative jurist Francis Bennion,” Justice Pollard said.

Does not offend or infect

According to Justice Pollard, Act No. 17 of 2000 does not offend or infect either Article 1 or Article 9 of our Constitution and is in full compliance with the provisions of the proviso of Article 164 of this instrument. “Consequently, its validity or constitutionality does not depend on the favourable outcome of a referendum as posited by the aforementioned learned judges of the Guyana Supreme Court.”

Justice Pollard urged that before terminating discussion on this issue, “It may be useful to remind the reader that in his judgment the Honourable Chief Justice (Acting) relied heavily on the relevant dicta of Chief Justice Conteh of Belize in the aborted Bowen v Attorney General and the judgment of the learned Chief Justice Sitri in Kessavada Bharati v Attorney General of India. However, Chief Justice Conteh in his relevant determination had identified the separation of powers doctrine and the rule of law principle as constituting the normative requirements of the constitution, both of which appear to be in compliance with Chief Justice Sitri’s “basic structure” doctrine of the constitution.” “Indeed, semantically, it is virtually impossible to construe the surrounding terms of “indivisible”, “secular” and “sovereign” employed in Article 1 of the Constitution as speaking to the disaggregated discrete rights of the electorate in a democratic society.

.jpg)