It is Oscar Sunday again; that time of year when cinephiles all over the world come together to watch, then complain about, the awards show that is supposed to celebrate the best in  film. The Academy Awards has faced a lot of criticism over the years, with its relevance being the main bone of contention.

film. The Academy Awards has faced a lot of criticism over the years, with its relevance being the main bone of contention.

Do the Oscars still matter? My response to this is, since when does rewarding art NOT matter? Is it not still important to have forums where work that would have escaped under the radar, and gone unseen by viewers (Australia’s Foreign Film nominee, Tanna, for example), are given a pedestal and placed in the limelight so people can know of their existence? When did celebrating art become irrelevant? Why is it not okay to be seduced by the power of movies and to allow ourselves to dream and fantasize on Oscar night?

These are just some of the reasons why the Academy Awards, in my opinion, still matters.

And yet, and yet, there are times when I do agree with everyone else who says that the Oscars has lost all relevance. Sometimes it has to do with the nominations(or lack of) in the acting categories, sometimes it’s about the Academy failing to reward the more deserving film, sometimes it’s about the Academy failing to even acknowledge the more deserving films (The Handmaiden did not get a single nomination, for example).

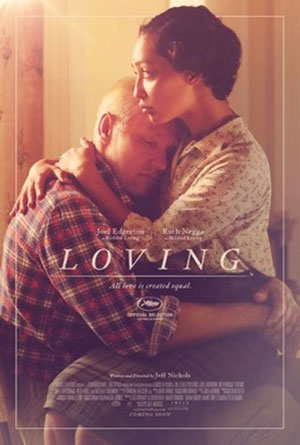

This year, one of my favourite films, Loving, directed by Jeff Nichols, gained only a single Oscar nomination and though it deserved so much more, by giving a Best Actress nomination to Ruth Negga (with one of the most competitive lineups in years to choose from), the Academy still managed to highlight a fast-rising talent and, eventually, still managed to bring [some] attention to the film by giving Negga a nomination – perhaps both the best and worst things about the Academy Awards highlighted in this single nomination.

Loving has all the makings of a Best Picture winner. It is set in, Virginia, America, in the 1950s, when interracial marriages are still prohibited in the county. Despite this, however, and despite knowing that they could go to jail, despite the implied misgivings of some of the people close to them, Richard Loving, a white man, and Mildred, a black woman decide to get married. What follows is the chain of events, including their arrest, their exile from their friends and family, the birth of their children, and the way their case makes it all the way to the Supreme Court, that leads to the case being used to challenge the prohibition of interracial marriage.

Content-wise, the film is a textured look at America, about life and love in the 50s, managing somehow to show both how far the country has come and how far it still needs to go. The Lovings, based on real people, are no grand heroes. They are not warriors and activists and politicians. They are quiet people, simply wanting to be together, to raise their children close to their loved ones, and to live their lives in peace. It is the simplicity of the lead characters and their needs that makes the story such a compelling one. It is a reminder that movies offer us a slice of life, in this case, real life, that makes us think and makes us feel and, ultimately, is supposed to make us want to do something, whether it’s simply becoming better people or leading a full-fledged revolution. Watching the story of the Lovings unfold before you, filled with tenderness and love, in another time filled with such familiarity, you can’t help not wanting to do both.

Joel Edgerton as Richard Loving gives one of his best performances ever. Edgerton’s portrayal of Richard is that of a quiet man, determined despite not saying a lot and more determined than anything else to ensure that his wife and family are safe. There is something warm about the character, in a way that reminds you of someone you know and yet, you can’t really have known Richard Loving. But perhaps, this speaks to Edgerton’s ability to enact the part in such a way that a familiarity is created with each audience member, using mostly only facial expressions and body language.

Alternatively, it is equally possible that the character’s position when it came to his family was something that was brought to the front of the character through the performance and this feeling of wanting to protect and love our loved ones is something that we can all relate to and this is what makes us feel like we know Richard. He reminds us of ourselves and of each other.

Ruth Negga is just as good as Edgerton. Watching her perform the role of a 1950s housewife in the American South and watching her nail the accent, it is easy to forget that she is an Ethiopian-born, Irish-accented actress. Yet, Negga captures a sort of fortitude that Mildred has, something that is different from Richard’s subtle strength because it is Mildred who seems more willing to believe in the effect their case can have not only in Virginia, but in conjunction with the Civil Rights movement. As you watch her, you get the feeling that she definitely knows that the situation is much bigger than she and her husband and you feel compelled to thank her for not slowing it down, but for speeding up the process.

It is quite easy to play a character who screams and shouts and vents all the internal turmoil and disquiet in the soul by being loud and talkative. It is much more difficult to do what Negga has done – representing conflict, emotions, confusion and chaos without once having to raise her voice. She more than deserves her Oscar nomination.

So while the film may not have garnered a Best Picture nomination, or a Best Director nomination (it takes real skill to tell this story so subtly without making it more than it needs to be), or nominations for Best Screenplay or Best Cinematography, we are once again faced with the debate regarding whether the Academy does indeed recognize the best.

Negga did land a nomination, and while we vent and get angry with the Oscars for not nominating Loving for more, we must simultaneously thank them for this nomination. It is a strange thing indeed that this one nomination manages to highlight both the bad side and the good side of the Academy Awards, and perhaps it is a reminder of the twisting, complicated nature of the issue of the Oscars. So, by all means, let the conversation and debate continue. There is still much to hear and much to discuss. Happy Oscar Sunday to all.

.jpg)