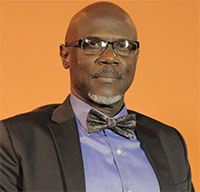

By Rear Admiral (Rtd.) Gary A. R. Best,

Presidential Advisor on the Environment

THE United Nations Environment Programme is the anchor global environmental

organisation. Its programme for 2010-2013 focuses on international cooperation, strengthening of laws and institutions in order to promote sustainable national and regional development, and access to science. It will also assist countries with technical assistance in international policy setting and national development planning (UNEP, 2010). This has largely been ineffective, and some have called for reform (Young 2008). However, As Mazi (2009) puts it, the United Nations Environment Programme, as the main body administering multilateral environmental agreements, was challenged by the formation of an increasing number of new agreements and institutions, which led to institutional fragmentation and loss of policy coherence in the work of the United Nations. Instead of organisational reforms, which are effective to resolve specific environmental problems, resort should be had to institutional changes, such as changes in structures of rights, rules, and decision-making processes to guide actors in relation to issues like climate change and bio-diversity (Mazi, 2009). On the other hand, Young (2008) believes that there is a call for environmental reform of the structure of international organisations that deal with environmental issues. Proposals include the strengthening of United Nations Environment Programme with universal membership and a secure budget, and the establishment of a United Nations Environment Organisation. Some have even called for the establishment of a World Environmental Organization similar to the World Trade Organisation. The Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development Issue Brief # 4 (UNEP 2011) informs that the Nairobi-Helsinki Outcome speaks to the upgrading of the United Nations Environment Programme and the possible establishment of a specialized agency, such as a World Environment Organisation. Upgrading to a specialized agency allows for autonomy and independent financing, along with treaty and convention-making powers. Current and future multilateral environmental agreements would then be negotiated under one agency, and all the present and future secretariats could possibly unite under one specialized agency.

However, according to Young (2008), reform in the United Nations Environment Programme is unlikely to result in changes in the systems of rights, rules and decision-making procedures. Institutional reform is indeed important, but the functions of institutions are more critical and should be resolved before reform is contemplated (Young, 2008). Ford (2003), who posits that current global environmental governance mechanisms leave out social grass roots movements, supports this view. In addition, where grassroots movements might be influential, co-option obtains to assimilate them into mainstream thinking.

Even though non-governmental organisations criticize the orthodox approach to environment and sustainable development, it is difficult to measure to what extent such criticisms affect the orthodoxy of approach when they are in fact designed by powerful states.

Compliance and dispute settlement are particular challenges to global environmental governance. In fact, the United Nations Environment Programme introduced guidelines on compliance with, and enforcement of, multilateral agreements which were adopted in decision SS. IV/4. However, these guidelines are advisory and non-binding, and do not alter obligations (UNEP, 2011 a). Crossen (2003) adds that even though compliance rates are high, the environment is deteriorating rapidly. He advocates the imposition of more onerous obligations in multilateral environmental agreements, and stresses the creation of strong legitimate enforcement systems which will move the process beyond compliance to issues of effectiveness.

A majority of environmental law is made within a treaty-based system, where consent is the trigger for creation of legal obligations and at the same time the factor that makes consensus difficult (Brunnée, 2002).

Compliance by national governments to international environmental agreements was boosted by the 2001 Aarhus Convention, which provides for citizens and non-governmental organisations to be auditors of the state’s obligations to international environmental agreements (Kravchenko, 2007). Aarhus allows citizen-state interaction which enhances environmental democracy. Quite restrictively, environmental law must not conflict with trade law. Whereas World Trade Organisation officials sit in on multilateral environmental agreement negotiations, the opposite is not permissible, neither is trade law required not to conflict with environmental law. In this regard, environmental non-governmental organisations have accused the global trading regimes of not assessing the impact of trade policies on the environment (Eckersley, 2004). The absence of effective compliance and dispute settlement regimes is likely to negatively impact climate change adaptation and sustainable development.

Despite evidence of climate change by the International Panel on Climate Change and the signing-on by states to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol, states’ attitudes to climate change remain, in the main, the same. In the result, the rich are called upon by the not–so-rich to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while at the same time suspicions abound among the developing states that the rich intend to thwart their economic growth and so they resist signing protocols. Even though the United States has not signed the Kyoto Protocol, some American states are meeting those environmental standards set by Kyoto.

There is a big difference, however, between the efforts in reference to the ozone treaty-making and climate change compliance, and that difference is cost. The cost for climate change is astronomical in comparison to obligations under the Montreal and Kyoto Protocols (Winchester, 2009).

Further, the Global Environment Facility has been accused of lacking transparency in its decision-making, due to the myriad of donors and their tendency not to deal with the specific environmental needs of recipient nations (Winchester, 2009). The donors, on the other hand, prefer to deal with abstract global threats, even though almost eight billion dollars were provided to developing states to deal with climate change, protection of internal waters, and ozone depletion. Ford (2003) strengthens this argument by stating that The Global Environment Facility pays more attention to the business and industry sectors, as opposed to the plight of citizens at the grass roots levels. The playing field was not level. The Global Environmental Facility became a perquisite mechanism for the South to participate in global environmental governance; but for the North, it was charity and therefore no compulsion for them to deliver on promises (Mazi, 2009).

| Mr Gary A. R. Best is a retired Rear Admiral and former Chief of Staff of the Guyana Defence Force. He is an Attorney-at-Law and is the Presidential Advisor on the Environment. He is a PhD. candidate at the University of the West Indies. He holds a BSc in Nautical Science (Brazil) and Masters’ Degrees from the University of the West Indies and the University of London. He is also an alumnus of the National Defence University and Harvard Kennedy School. His research areas include climate change governance, climate change finance, international relations and environmental law. |

.jpg)