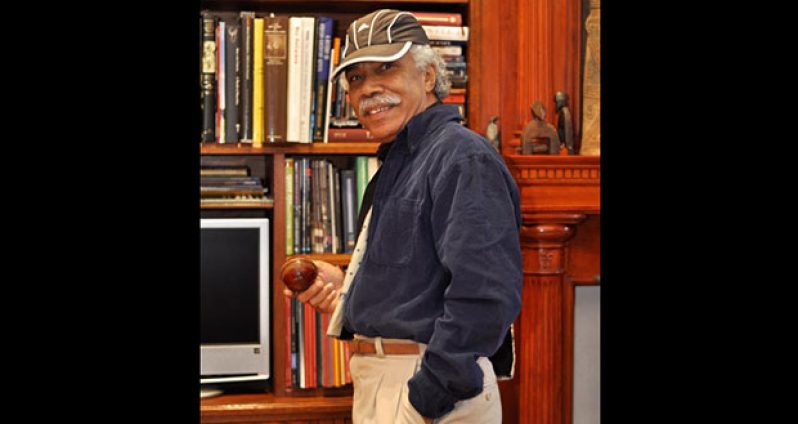

by Terence Roberts

By the 1980s, when the circulation of classic Hollywood films and subtitled European films from Italy and France began to end in Guyana, due to both new national ideological priorities, and inventories by film studios with plans for the video-cassette revolution, all the local Georgetown booking offices for such film studios were closed, and thousands of these film reels stored in Georgetown were shipped back to the Metropolitan countries.

So intrinsic to the intellectual and social growth of Guyanese society was this cinematic period which lasted at least six decades that the negative effect of its absence would be felt on: (1) Both the self-pride cultivated by creating personal fashions, and an open-minded social attitude and behaviour among individuals; (2) the previous ability of citizens to accept their collective national identity as preferable to promoting insular ethnic values; (3) On the unguided behaviour of a new post-1980s generation of Guyanese, some of whom went abroad and ended up in unlawful activities, incarceration, and deportation.

So intrinsic to the intellectual and social growth of Guyanese society was this cinematic period which lasted at least six decades that the negative effect of its absence would be felt on: (1) Both the self-pride cultivated by creating personal fashions, and an open-minded social attitude and behaviour among individuals; (2) the previous ability of citizens to accept their collective national identity as preferable to promoting insular ethnic values; (3) On the unguided behaviour of a new post-1980s generation of Guyanese, some of whom went abroad and ended up in unlawful activities, incarceration, and deportation.

A large part of the inspiration behind a prior gentlemanly and debonair, ambitious and cultured (even when adventurous) attitude of Guyanese men and women between the 1920s and 70s came from the massive amount of classic film culture they consumed collectively during those decades.

The whole idealistic point of such films aimed to capture not just the price of cinema tickets, but offer a model, or standard of attractive characterization, one gained by emulating in some benign manner, actors like Ronald Coleman, Dana Andrews, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, James Stewart, Tyrone Power, Joel McCrea, Clark Gable, Gregory Peck, Montgomery Clift, Rock Hudson, Randolph Scott, Sidney Poitier or Harry Belafonte, in most of their film roles.

To a large extent these actors led the way in providing examples of male sensitivity, reform, humility, stoic optimism, humour, tolerance, family values, fair play, kindness, ambition, and innovation, in films like: Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939); Random Harvest (1942); Only Angels Have Wings (1939); The Awful Truth (1937); The Best Years Of Our Lives (1946); Daisy Kenyon (1947); Gentleman’s Agreement (1947); The Hucksters (1947); Any Number Can Play (1949); Seven Men From Now (1956); Man Of the West (1958); Ride Lonesome (1959); Westbound (1959); Comanche Station (1960); The Misfits (1961).

Other actors like Robert Taylor, John Garfield, Charleston Heston, Richard Widmark, Paul Newman, Anthony Quinn, Laurence Harvey, alerted Guyanese male film viewers to the hasty, stubborn personality traits that could turn them into egotistical and macho men, mentally unbalanced individuals, corrupt professionals, racists, rapists, or ruthless social climbers and schemers.

All characterizations profoundly explored in insightful films like: The Naked jungle (1954); Party Girl (1958); The Far Horizons (1953); Body And Soul (1947); No Way Out (1950); Night And The City (1950); Room At The Top (1958); Last Train From Gunhill (1959); Take A Giant Step (1960); One Potato, Two Potato (1964) etc.

The absorption and comprehension of such films, sometimes seen more than once because the opportunity existed via their rerun circulation locally, made a previous older generation of Guyanese men who went abroad to Metropolitan countries in the 1950s and 60s, able to handle such Metropolitan societies with a prepared and strong experienced mentality, which in turn helped them to avoid criminality.

Whereas it seems many of a younger generation who were born after the 1970s, when the opportunity to see these films in Guyana had ended, drifted into wayward circles, drug trafficking, addiction, and criminality abroad, and were often deported; a development unheard of among previous generations of Guyanese immigrants.

For Guyanese who lived in the hinterland and along the coastal rural countryside, who were involved mainly in a proletarian agricultural lifestyle, the process of their social education and refinement involving multi-cultural communities and environment, race mixing, etc, could not be explored or taught only by schools, churches, temples, mosques, or community leaders, since such an experience was too new, expansive, and sensitive. The broad narrative content of numerous classic Hollywood films therefore staged countless examples of personal and social problems, while opening knowledge far beyond the various inherited one-dimensional interests of such rural districts.

The country cinema therefore became a major site where local rural and ethnic relevance was found in films with similar Western frontier communities, for example: wooden dry goods stores stacked with raw produce and materials, community gossip, superstitions, bigotries, stereotyping, etc.

Films like: Barbary Coast (1935); The Grapes of Wrath (1940); How Green Was My Valley (1941); Canyon Passage (1946); Duel in the Sun (1947); Broken Arrow (1950); The Big Sky (1952); Shane (1953); East of Sumatra (1953); Return To Paradise (1953); Bad Day At Blackrock (1954); Apache (1954); Taza Son Of Cochise (1954); Broken Lance (1954); Cattle Queen of Montana (1954); Apache Woman (1955); The Far Horizons (1955); The Rains of Ranchipur (1955); East of Eden (1955); Foxfire (1955); Oklahoma (1955); Giant (1956); The Spanish Gardener (1956); Island in the Sun (1957); The Big Country (1958); The Sheepman (1958); God’s little Acre (1958); Porgy and Bess (1959); The Fugitive Kind (1959); The Old Man and the Sea (1959); Wild River (1960), etc. The proof that such films appeared in Guyanese cinemas between the 1930s and 70s, exists in local newspapers of those decades.

The damaging gap left in the continued refinement of Guyanese society due to the end of such selected film programs in Guyanese cinemas, also encouraged the increase of insular ethnic cultural acts after cinemas lost their original owners and were converted by new owners into venues for East Indian films alone, especially in neighbourhoods of multi-cultural and multi-racial citizens who were the majority of previous patrons.

Obviously attendance dropped, since such ethnic films from India (which in any case appeared at special programmes almost every cinema offered), did not possess, or contain, the broad relevance of diverse races and cultures interacting, or the social subject matter of classic American cinema, which all Guyanese were accustomed to and which also matched the national reality they shared.

As regards the ability of these past Hollywood films to analyse and explore the various motivations and solutions to criminal activities, Guyanese society in the past was saved much of the senseless violence and criminality it contains today. To look at: Ladies They Talk About (1935); The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946); White heat (1949); Johnny Eager (1942); The Asphalt Jungle (1950); Night And The City (1950); Party Girl (1958); Seven Thieves (1960); Cry Tough (1959); Once A Thief (1960), provides just a sample of films which defuse potential crime motivations which seduce the gullible today; also such films, along with recent new ones like : Bullitt (1968); Serpico (1974); Heat (1995); or Crash (2004), are perfect educational entertainment of specific film programs for Guyanese prison inmates, police, and other law makers today.

Up to the end of the 1970s Guyanese society was filled with intellectual interests and an optimism generated by the exciting, constant, public showing of such films in local cinemas. Even after the destructive political and racial violence of the early 1960s, Guyanese society quickly returned to everyday normality under the daily social guidance of such films in its cinemas. It would turn out to be the last wave in a golden age of Guyanese patronage of classic international film culture which needs to be once again locally known and understood.

.jpg)