WE were all young men; none of us pioneers were yet 20 years old, but we were not to be confused with the National Service. Of course, we came from different backgrounds, with different grass-root stories, but when we all landed at Kuru Kuru in 1973, the one thing we were certain of was that we were there to help build a multilateral college, and we would be the first students.

That was the lure the recruiters used to entice us to join the Pioneer Corps that would enter Kuru Kuru. We would all later understand why that lure was concocted, because parents understood the necessity of trade-skill training, as against this new concept of the State agenda of agricultural cooperatives.

We were given a stipend of $20 a fortnight, of which $4 would go to savings. Some of us, like my buddy, ‘Big Bear’ Cyrus Boyce, were chainsaw operators; we were building log cabins for the managerial staff and their wives.

We pioneers were located in tents on the slope leading to the memorable Kuru Kuru Creek. Our toilets were the surrounding forests, which we engaged with cutlass and shovel, well aware of the Annie ants whose bite would temporarily paralyze, with fever.

We offered support to the professional builders, supplying water to big contractors like Turner & Sons. We also acquired night construction work with the local small contractors like Mr Pickering at reasonable wages, because those funds bought the ‘drain pipes’, ‘fat pants’ and chambray shirts for our visits to The Nook at Soesdyke, where girls, music and beers lay waiting.

THE STUPID MYTH

We were young men who ran on the two-and-a-half-mile red loam road, from the Linden Highway, because someone had started the stupid myth that jaguars liked to pounce on lazy strollers.

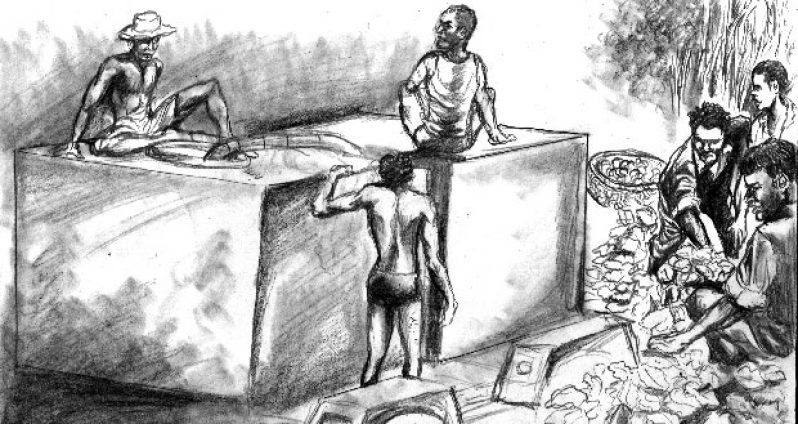

Subtly, we were guided into farming projects. We were taught block-making with the right mixtures. One of our first projects was to build a piggery, then chicken pens that were located further away. (We were forced to reinforce the pens after the ocelots had a chicken feast. We enjoyed their frustration when attempting to breach the stronger fencing; we shone those field hand-torches and watched as they retreated into the bushes).

At Kuru Kuru, I began to hate our zoo, which, to my mind, was a sanatorium for animals, whose natural instincts were being stifled in those small cages.

We developed farmlands further along the creek; this had to be done skilfully because the soil of that part of the highway was not very conducive to cash-crop farming.

Only one man was planting pines on the ‘Highway’ then; one Mr. Glasglow, who also sold cigarettes. And according to Skipper Gordon and Copper, who managed us, he made a mean local liquor.

We were later moved to some barrack rooms, which were built by GDF ranks, with our support. We still slept on ‘jackasses’ (bush wood expanding crocus-jute bags). We were upset when the catering girls were moved in with proper beds in their spanking new dormitories.

THE PROTEST CARTOON

I drew a protest cartoon, and we delivered it in quite a serious mood to the principal, Mr Basil Armstrong, whom we liked. We then retired to bed, grumbling to our ‘jackasses’.

About two weeks later, the Minister of Cooperatives, William Haynes, came into our corner of the now finished college with enough beds, talking about the little cartoon. The Minister was in a good mood, so we relaxed, and thought that this was the end of the cartoon protest. We were so wrong.

Back then we were called K.A.Y.S., or Kuru Kuru Agro-industrial Young Settlers Coop. We had worked our way into the initial government plan, and were now comfortable in that mould.

The Kuru Kuru Coop College was launched in early 1974. The group of young men that comprised KAYS was the support labour that built that institution.

At the launching, Prime Minister Forbes Burnham urged us to be independent; to value our labour and not to end up having to retire at 55, then die a few years later from a feeling of hopelessness in the prime of our lives.

Then after the speech, he spoke about the now infamous protest cartoon. I wanted to sink into the earth, but my fellow pioneers urged me forward.

His words to me that day were: “Use your talent to tell the stories of our heroes,” heroes I was unaware of at the time. But that’s another story.

LIFE AT KAYS

KAYS had to function within a co-op business format; sell to co-ops mainly. This was frustrating, as many of the co-ops were hardly managed by business people, and proved our worst nightmares.

While as secretary [at 17 years old], we cultivated an independent group of support with people like Blaire’s Delight at Linden, who would drop in and order produce then return for his order and leave a cheque.

There was a co-op at Linden that was hopeless. We also took on contracts from the College. Many tired evenings, we absorbed the lessons on book-keeping taught to us by Mr. Lakeram Persaud.

This would come in useful months later, when we were visited by a group of lily-white shirt- jacked folk. That’s the first time I would hear the word ‘auditors’.

They proceeded to ask questions about how we operated financially. Our esteemed college staff would frequently send the catering girls to pick up eggs, chickens, tomatoes etc from us.

Following Mr. Persaud’s cue, I had them sign details consisting of: For whom, amount, and their signature on behalf of whom.

The auditors left as calmly as they came. The college staff were a little stiff with us for a period, but things soon returned to normalcy.

BOYS TO MEN

We had grown from boys to men. By then, the college had students from the Caribbean and the University of Guyana.

Miss Vashti Werner was the head of the Home Economics section; Rigby Dover was our manager and secret political mentor. Nurse George was the resident medical person; so when my left foot was burnt while attempting, with Chalmers, to light the fireside with gasoline, I became domiciled in the college’s exclusive medical quarters.

There I was nurtured and fed by the ‘home-ec’ girls, whose food was heaven compared to Brother Fitzroy Billy’s elastic eat-now-or die bakes, and Cookie’s skim-milk laxative cook up.

Eventually, ‘Orlando’ Gordon, Bamfield, and some other KAYS members grudgingly escorted me away from the comfort of the medical quarters.

THE CONNIVING ACCOUNTANT

One incident that resonated with us all was when we approached a gentleman who was the accountant at the Ministry of Cooperatives about the $4 saved for us while we were pioneers.

With me were Gordon, Tilak, ‘Pointer’, Bamfield and others. We stopped this man and, pointing at me, he responded: “What are you and them going to do with money?” We were too shocked to answer as he walked away.

Years later, in 1991 at Luciano’s Snackette on King Street, there was the gentleman. By this time, he was part of a popular anti-government movement, with a small audience.

His self-righteousness was aggravating; so, reminding him of our pioneering savings, and his arrogance. I even implied that he stole it. That was too much for the goodly gentleman, so he left.

Too short is one article to tell the story of KAYS and its environment. I conclude by mentioning the following names, as I remember them:

Brian Hector; ‘Swagger’ Jones; ‘Fat Boy’, whose hobby was minding scorpions and snakes as pets; Lloyd Pickering; Murtland Paul; Keith James; Percy Muhkram; Chippy Luke; Jap-head; Eric Hohenkirk; Rudolph and Sammy; ‘Baby’Norman, the youngest; Harry Narine; and the memorable ‘Joe Slay’ Fernandes; ‘Quarters’ Barnes; Erleen; Grace and the aatering girls; Terry the electrician who married Erleen; and too many others whose energies demonstrated that the positives of Burnham’s co-operative movement, in this case, was ahead of the bureaucracy mandated to shepherd its success.

.jpg)