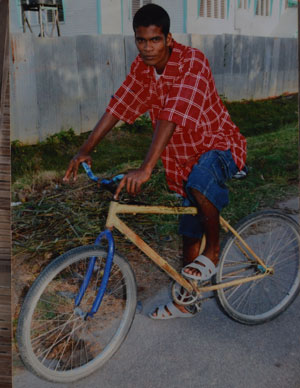

ONE year has passed since 23-year-old Sanjit Sukhram, a GuySuCo dock worker who was attached to the Enmore Estate, died mysteriously during a fishing expedition with friends at Hope Low Lands, East Coast Demerara.

A lanky young man, Sanjit was also called ‘Tall Boy’ by his friends and ‘Boy’ by his immediate family members.

He was an Enterprise Garden resident, and was the last of eight siblings. Belonging to a poor family in the sleepy East Coast Demerara village, Sanjit was forced to drop out of school and do odd jobs to help in the sustenance of a large household.

A helpful and humble son, he was loved by his parents and had many friends, some of whom his parents — Mahashwar and Kalouty Sukhram — were warned about, but they never paid attention to what they were told.

Today, they both told the Chronicle that they strongly regretted not taking the advice of neighbours, as they called on the authorities to revisit the case of their son’s death.

Mahashwar is a retired cane harvester, while Kalouty is a housewife. They are both from humble beginning, and their current standard of life can, by any stretch of the imagination, be described as humble.

Neither Mahashwar nor Kalouty went far in school, and when they were informed of their son’s death on that fateful day, May 22, the news struck them like a lightning bolt.

They did not know what to do, and even though they threw their hands in the air, asking for guidance and help to get to the bottom of the facts surrounding their dear son’s death, no help was forthcoming.

APPEAL

The elderly parents are now calling on the National Security Minister, Khemraj Ramjattan, to use his good office and reopen the case of Sanjit’s death.

A thorough investigation, they say, would allow them to rest comfortably, as it would bring a satisfactory closure of the matter.

On May 22, 2014, Sanjit drowned while on a fishing expedition with five friends, including two males, at Hope Low Lands. His death certificate indicated that he died of drowning, and the cause of death was given as asphyxiation.

There are a few things Mahashwar and his wife Kalouty told this publication that are strange surrounding the circumstances of the death of their last child.

Sanjit had developed a close friendship with an Enterprise Garden family who lived two streets away from him.

Kalouty said her son would spend time, cook and eat at that family. Sanjit also used to have regular weekend drinks there, but never misbehaved when he came home.

Moreover, he did errands for the family, went with them on outings at friends, and on their visit to relatives at the creeks.

Kalouty said her son did not know how to swim, but that the male relatives of the family who went with him fishing on the fateful day at Hope Low Lands knew how to swim.

She related that she interacted with the family on a few occasions, noting that her relationship with them was not close, largely because she likes to enjoy her space.

Her husband also said he had met the family a few times, and his interactions with them were also few. He said what he heard about them from neighbours was unpleasant, but he dismissed the talks as usual bickering.

This publication inquired from him what he was told, and he related that neighbours had confided that the family friends of his son do strange and eerie things.

FLUTTERING OF FOULS

He said they related to him that, late in the night, they would hear the screaming and fluttering of fouls, and it would make them cringe in fright. The Guyana Chronicle was told that the affected neighbours never made a complaint of noise nuisance to the police.

Mahashwar said he was not too inclined to believe the story, since he knows that the neighbours and family members “don’t talk”, and because he knows that people say nasty things of others whom they do not like. For his reason, the father said, he never stopped his son from visiting the family.

He recalled that Sanjit had slept at the Enterprise Garden family on the night before the day of his death.

His wife, in tears, related an interesting bit of the story. She said that a few days before her son’s death, a close and elderly relative of the family had asked her what she would do if her son should die. Kalouty said she was stunned by the question, but responded: “How me pickney gon dead, and for wha?”

The question, she said, had disturbed her to the extent that it had taken a few days for her to get it off her mind, but she never stopped Sanjit from visiting the family.

She related that on May 22 last year, the day Sanjit died, he had told her that he was going fishing with the family in a party of six, including himself. Kalouty said she was cooking on the fireside in the yard at the time he left. He went separately, in a taxi, joining the family at Hope New Lands. Going fishing with the family, she said, had been a regular thing for her son.

‘TALL BAI’ DEAD

Before she could finish cooking, the phone rang, and an elderly relative of the family told her “Tall bai dead!”

Deeply disturbed and distressed by the sudden and tragic news, Kalouty said she and her husband took a taxi and rushed to the scene. When they arrived there, she was screaming “Wheh me son deh!”, “Oh Gad, bring him back!”

The mother related that she had seen two male relatives — one was sitting with his arms folded and his “cast net” flung over his shoulders; the other approached her to say “Boy asedrum bust”.

Crying and screaming, she had asked how he knew that, and was told “Boy drowned”. Both men, she noted, were red in the eyes, had mud on their skin, and appeared to be intoxicated.

She said that when she inquired why they did not try to save her son, a female relative who was with them told her that if they had tried, they too would have drowned, since they were intoxicated.

By thiat time, the distressed mother said, scores of persons had flocked the scene, and she saw a “black boy” (African) on the bridge near to where the incident happened.

She asked him if he knew about her son’s death, and he related that he was told by the family members who were on the bridge that someone had drowned.

Incidentally, the African youth was working on the bridge. He said that while he was told that someone had drowned, the family members with whom Sanjit had been did not say where he had drowned.

The mother said that when she asked the family members, a female among them told her that Sanjit had plunged into the middle of the trench and had not resurfaced.

According to Kalouty, the boy on hearing where Sanjit reportedly plunged, quickly boarded a taxi and collected a friend. And within minutes, they returned to the scene and went in the trench to search for her son. And they found him!

MUD IN MOUTH

Kalouty said Sanjit was found at the shoulder of the trench and not at the middle, and when he was brought to land, there was a lot of mud in his mouth.

She said the African boys and the scores of persons who had gathered at the scene began to point fingers at the members of the family who were with Sanjit, telling her that if they had raised an alarm, the life of her son would have been saved.

Vishal Sukhram, a brother of the dead man, told the Guyana Chronicle that he was invited to witness the post-mortem examination, but was prevent by a police officer from seeing the exercise when he got there.

He said that when he asked why he was being prevented from witnessing the post-mortem, the police officer told him that he (the policeman) would deal with the matter. Vishal, nevertheless, said that after the post-mortem, the officer told him that he had observed mud in his brother’s stomach and in his lungs.

The post-mortem was performed by Government Pathologist Dr Nehaul Singh, and the cause of death was given as asphyxiation. Both Mahashwar and Kalouty suspect something fishy about the death of their son.

Kalouty told this newspaper that she had given a report to the police on the day her son had died, and after his post-mortem, she was asked to visit the police station, but being deeply distressed and confused, she did no go.

The members of the family with whom Sanjit had been at the time of his death were reportedly questioned, but none was charge.

After the funeral of his son, Mahashwar related, he had heard of whispers from relatives of the family that Sanjit had gone mad and had probably committed suicide.

A thorough investigation, he said, would reveal the truth of how his son had died.

By Tajeram Mohabir

.jpg)