Introduction by Lynne Macedo University of Warwick

The writer, performer and tutor Maggie Harris was born in New Amsterdam, Guyana in 1954 and attended Berbice High School. In 1971 she moved to the UK and, as a mature student, studied at the University of Kent where she achieved both a BA Honours in African/Caribbean Studies and a Masters Degree in Post-Colonial Studies.

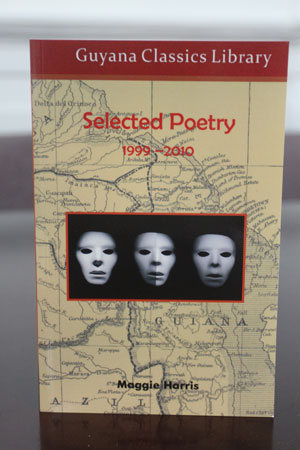

She has published five collections of poetry to date – Foreday Morning (1999), Limbolands (2000), Dancing with Words (2001), From Berbice to Broadstairs (2006 and After a Visit to a Botanical Garden (2010), and also written a memoir entitled kiskadee Girl (2011). Harris has received numerous awards for her work, including Kent’s Outstanding Adult Learner in 1994, a Leverhulme scholarship to research performance poetry in Barbados in 19999, awards from Meridian TV, the Arts Council New Writing, the T.S. Eliot Student Prize from Kent University, and Kingston University Life Writing. In addition, her Limbolands collection won the Guyana Prize for Literature in 2000. Harris also created the first live literature festival in East Kent – Inscribing the Island – was a founding member of the ‘White Women’ group, has performed her work in Europe and the Caribbean, and has been widely anthologized.

Much of Harris’s work is concerned with what a reviewer of Limbolands aptly described as ‘a collision of cultures’ and this desire to explore and articulate cultural and racial hybridity is evident throughout the poems which form this new volume. Representing a cross-section of her writing from the past eleven years, these poems illustrate the myriad ways in which her skilful use language – both Creole and Standard English – is employed to explore a range of issues such as motherhood/motherland; identity; exile and alienation; and to (re)imagine events from the Caribbean’s turbulent past. It would be hard to underestimate the importance of re/memory for Harris, who clearly draws upon the diversity of her Guyanese background as a major source of nourishment for both her creative imagination and the hybrid, trans-cultural sense of self that informs her poetry. As she writes: “I come from the borrowed names, given names, names of dispossession…I come from skin and bone, Portuguese skin, African bones/buried in forgotten oceans”, and it is this ability to straddle different words and mindsets that makes her poetic voice so distinctive.

By opening this new collection with a poem entitled ‘Origins’, Harris immediately draws our attention to the centrality of this concept of her body of writing. Some of the most powerful images about ancestry and belonging are evoked in those poems which explore the notion of what it means to be an individual of Caribbean origin, someone who must deal with all the cross-cultural; racial; and geographical collisions that such a heritage entails. “Trace me that line of ancestors on that shore/Ibo, Hausa, a Madeiran fisherman drawing his nets off a reef/Waters that flow from Chechnya and the Nile.” In ‘Mapping’ for example, the child of a ‘brown-eyed Mama and grey-eyed Dada’ struggles to find sense of self from within that indeterminate space of mixed racial heritage: “Dr. Ferdinand…/slap me, left me, cry me, write me, label me/like a cocktail: ‘Mixed’…/…centered me neatlt in limbo”. That notion of limbo – the inability to neatly slot into a pre-defined area belonging, particularly for the “mixrace/whiteface gold hair girl” – is one that Harris revisits in several other poems, most notably in the aptly titled ‘For all the seeds planted by men in foreign soils and left to harvest themselves’. “Lord Jesus, since mih Daddy gone/It seem that Ma don’t want we/…She say she cyant stand blue eye/Is like he lef he ghost behind/…No-one want white man pickney”.

This dialogue about the shifting nature of identity is by no means confined just to those poems that are specifically located within Guyanese context. In ‘Solomon’s Wisdom’ Harris provides the witty but poignant perspective of a Caribbean migrant to Britain, a ‘confuse woman’ who worries about her future in ‘the motherland’: “You see Solomon, mih old granddad he own plantation/ Mih old granma she work plantation/…So I thinking hard about repatriation wondering/Which pieca me going to go through which gate?” Many of the issues which inform ideas about racial and cultural difference are given further consideration in ‘Alien In-Transit (or Travelling on a Guyanese Passport)’. Even the typography of the poem – specifically the diminishment of ‘I’ to ‘i’ – is utilized to draw the reader’s attention to the all-pervading sense of isolation that the narrator experiences in an airport interrogation about their right to entry: “that I should be so audacious as to claim/expect, believe/a focused i, a real i, a truthful i/ is challenged with sharp rapier thrusts”.

Harris has continued to foreground the freedom of her poetic imagination to question the relevance of a mixed sense of self in works such as the title poem from her 2006 collection, From Berbice to Broadstairs. Once again faced with those seemingly endless questions about belonging – “Come far?’ The taxi driver asks”, she resists assimilation into any preconceived concept of identity: “You’re the only Caribbean I know’ she says/ and my tongue rolls back in my throat/’Guyanese ‘, I whisper, ‘Guyanese’. Guyana, not Ghana, South America, not Africa./ I am neither a small island girl nor am I a region.” That one word ‘Guyanese’ may encompass all aspects of the heritage from which Harris draws her strength and inspiration, but clearly the clash between a Caribbean imagination and an English context is one that resists easy resolution within the confines of her poetry.

Harris has lived in the UK for more than forty years, yet her poems constantly remind us that memories of a Caribbean past not only shape her sense of identity but also inform the ways in which she relates to contemporary Britain. In ‘Palm Houses’, a visit to a seemingly ordinary Botanical Gardens in Wales quickly alters into something far more evocative, as the narrator becomes transfigured into and through the Caribbean-like flora which it contains: “I enter, a native daughter, barefoot/mouth open like a bromeliad/the hair on my arms rising/like cactus spines.” Another of her poems which is tellingly untitled ‘On the Limbo Train, uses the unlikely medium of a train journey to further explore the transformative quality of memory. Beginning with the Caribbean setting in the late 1950s, the poem gradually shifts both time and location to England fifty years later, yet all through what ostensibly appears to be a single journey: “And so we go, shunted away on runners taking us/ From here to there, and in our heads dream…” This blurring of boundaries between the physical journey and that of the path to self-awareness of what it really means to have taken the journey from Guyana to Britain, are all encompassed in those dramatically shifting images which, despite everything, cannot stifle the creative imagination: “You could still dream through; stare out the window.”

The exploration of the ambiguities inherent in her position as a migrant writer may be a major theme in her writer, but it is only one of several which thread through Harris’s poetic output. Remembering her own past in Guyana is closely allied to re/membering her country’s past, with the intermingling of diverse races and cultures through a history shaped by colonization, slavery and indentureship. In ‘I, Breadfruit’, for example, she takes the bold step of writing from the perspective of the vegetable itself, which was first taken to Jamaica on the Bounty as a food source for the African slaves. “I, Breadfruit, am traveller/eyes bright ad mouth shut/ Am survivor extra-ordinate/Mister Fletcher, Captaine Bligh/ You have writye me into Historye Booke!” It is just not the subject matter but also the specific type of language used – a king of broken, 18th century form of English – that makes this particular poem so memorable, providing the reader with a highly creative glimpse into a little-known aspect of the region’s history.

The backdrop of slavery provides the context for several other poems in this collection such as ‘Onwards’, ‘In the Wake of the Santa Maria’ and ‘Free Coloured, 1810’. The latter work celebrates the onset of freedom that has just been granted to a mixed-race woman – part of an ever – growing element of Caribbean society of that time due to widespread (and largely unsolicited) sexual liaisons between white ‘Masters’ and their black, female slaves. “My honourable father he/ set me at table wait/ he know full well I was his seed/…He not to blame for he had need/ to keep his name from stain/…Sweet liberty! That pen and word should be/ so glory be and sun no longer my face! Those first, free steps towards a new world order in which ‘pen and word’ can finally give voice to the dispossessed, emphasizes Harris’s belief in the immense power of language, and its unique ability to like the present to previously untold stories from its vanished past.

The strong ties which bind Harris to the past, present and future of the land of her birth – her motherland – are mirrored in their intensity with those poems which deal with family relationships, particularly those between daughters, mothers and grandmothers. As Dieffenthaller has commented: “A central concern…(in Harris’s poetry) is a meditation on motherhood and its post West-Indian condition…Harris’s poetry (itself) becomes a king of motherhood.” Poems such as ‘In my Mother’s house there are many mansions’ openly celebrate the affection between (grand)mother and child whist, at the same time, highlighting the generational shifts in ways of dealing with an ever-evolving world: “How were you to know that times would change/…that the time for swords, too, would pass/…again we need/ the time for words, for praise songs to the elders/ for memories to weave within the skins of our children.” It is interesting to note that as in ‘Free Coloured, 1810’, the primacy of language – ‘the time for words’ – is singled out as the most important gift that a child can inherit from its ancestors.

Not all the relationships that Harris writes about are, however, so straightforward and in ‘Fifteen’, ‘Blame’, ‘Words Across the Water’ and ‘Grandmothers of the Morning’ she articulates more anxieties about the nature of the maternal bond. “So what can I tell you/ that you don’t already/know/..you walk your own road; I’m the mother dragon breathing fire form the hill.” As a migrant mother who lives in England she worries, with just cause, that her daughters will be unable to continue that matrilineal link to the (mother)land of her own birth: “of course I am to blame/ how can one chant praise songs to field and plains/ your children never claimed/…so if my children dance to other drums/ and speak in different tongues/ whose fault is it but mine?” Harris’s poems acknowledge that there are no easy answers to such musings, yet the repetition of the line “My daughters walk the deserts of unknowing” provides us with an apt and poignant refrain.

It is apparent that the character of the migrant experience is viewed by Harris as but another level in a complex relationship with the mother/land, one which constantly reconfigures the links between her (female) narrative voices to multiply yet receding points of connection with their Caribbean heritage. It also seems likely that Harris will carry on exploring such matters with an increasingly confident voice, and continue to articulate a desire for ‘home’ that is forever filtered through a lens of distance. As Barbara Dordi has so aptly observed: “…Maggie Harris may have lost her accent but Guyana has her firmly in its grip still…”

.jpg)