ONE day, Sampat Pal Devi, a resident of the Banda District of Uttar Pradesh in Northern India, saw a fellow villager beating his wife.

Sampat implored him to stop, but he paid her no mind. When she tried to intervene, the man turned around and abused her. Incensed at his temerity, she rallied a few women and went back to the man’s house the next day, and gave him a sound thrashing.

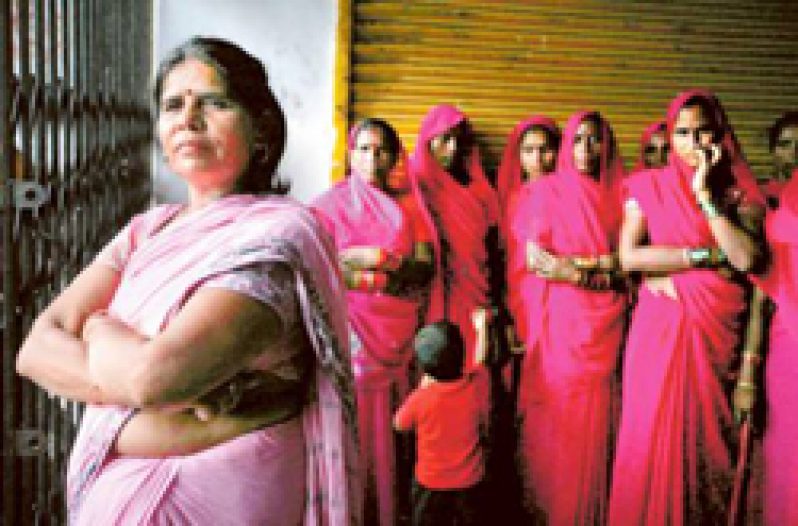

Lesson taught, they went their separate ways; but the incident had succeeded in creating a ripple in the village. Realising the power of togetherness, Sampat formed the Gulabi Gang, an NGO to help women in distress and fight for their rights. Over time, more and more women began joining the gang. They pay a membership fee, and are provided with a pink (gulabi) sari and a long stick as a uniform.

Lesson taught, they went their separate ways; but the incident had succeeded in creating a ripple in the village. Realising the power of togetherness, Sampat formed the Gulabi Gang, an NGO to help women in distress and fight for their rights. Over time, more and more women began joining the gang. They pay a membership fee, and are provided with a pink (gulabi) sari and a long stick as a uniform.

Asked about her predilection to fuschia, Sampat said: “Most colours are associated with political parties or religious groups. Pink has been my favourite, and I believed in having a uniform, which removes any kind of disparity, and creates discipline. It is also easy for people to recognise us.”

Today, seven years later, the group has grown to more than 20,000 members, and continues to grow. Arming themselves with long sticks, the Gulabi Gang came into being as an independent force of justice, with the aim of “punishing” oppressive and violent fathers, husbands and brothers.

Arming themselves with long sticks, the Gulabi Gang came into being as an independent force of justice, with the aim of “punishing” oppressive and violent fathers, husbands and brothers.

Eventually, the vigilante group began to defend other vulnerable groups. Sampat says, “It is not only about feminism; we fight for the oppressed — men, women and animals. We confront people who rape or raise their hands on women. People would kill their newborn on finding she was a girl; we deal with them firmly.”

Sampat made the headlines back in 2007 when she slapped a policeman on duty at the Attara police station. Incidentally, the fight this time was for a man, against whom no report had been filed, but was detained unlawfully. The slap reverberated throughout several villages; and Sampat rose to both national and international fame.

Rise to fame As the world learnt about the group of women in pink sarees, dispensing their own brand of fair deal, villagers began flocking them to get justice in matters related to corruption and oppression. Sampat’s time had come. She became a heroine, and militated in favour of girls who wished to study and become independent. She also challenged stereotypes, and intervened where the Law refused to help, and age-old traditions exploited women.

As the world learnt about the group of women in pink sarees, dispensing their own brand of fair deal, villagers began flocking them to get justice in matters related to corruption and oppression. Sampat’s time had come. She became a heroine, and militated in favour of girls who wished to study and become independent. She also challenged stereotypes, and intervened where the Law refused to help, and age-old traditions exploited women.

Her feistiness has secured notable victories for her community. In 2008, the group ambushed the local electricity office, which was withholding service until members received bribes or sexual favours in return for flipping the switch back on. The stick-wielding gulabi stormed the company’s grounds and proceeded to rough-up the staff inside the building. An hour later, the power was back on in the village. The modus operandi of the women in pink sarees is to confront the offenders and humiliate them in public. The gang makes the person feel so ashamed, that the mistake is never repeated again.

The modus operandi of the women in pink sarees is to confront the offenders and humiliate them in public. The gang makes the person feel so ashamed, that the mistake is never repeated again.

The context of this phenomenon? As one writer explains it, the host of ills plaguing modern India, such as honour killings, dowries, child marriages, and female feticide account for female despondency; but not for gangs such as Sampat’s, which have an outlet for it. In the past, many Indian women would have taken these pressures out on themselves, through self-immolation or hanging, for example.

But as women began to gain political power through initiatives like the Affirmative Action Bill, he said, dispossessed rural women have come to realize that they can instead respond boldly and collectively to abuse. So then, why aren’t they turning to political activism, as opposed to vigilantism?

Firstly, gangs offer more immediate benefits than politics does. Another reason is that female politicians rising to power from the lower castes have been dismal role models. These politicians may have the potential to inspire poor women more than dynastic leaders like Sonia Gandhi, but they have disappointed the women they claim to represent by being as corrupt and as criminal as the male politicians they so despise. Following the recent death of a 23-year-old victim of gang-rape, women’s rights issues have shot to the top of India’s social agenda; and the Gulabi Gang is right there in the mix, demanding justice.

Following the recent death of a 23-year-old victim of gang-rape, women’s rights issues have shot to the top of India’s social agenda; and the Gulabi Gang is right there in the mix, demanding justice.

Five of the accused have since been charged with rape and murder, while a sixth suspect, who claims to be under 18, is expected to be tried in a juvenile court separately, the Associated Press reports.

Under Indian law, juveniles cannot be prosecuted for murder. According to a police report seen by the Hindustan Times, it was the youngest suspect who “extracted her [the victim’s] intestine with his bare hands, and suggested she be thrown off the moving vehicle devoid of her clothes.”

The Indian media reports the police are pushing for the death penalty, but the Gulabi Gang is opposed to capital punishment. Sampat believes the death penalty “worsens the scenario instead of mitigating the problem,” and that illiteracy is the reason for the growing incidents of rape.

As she told The Times of India: “The rapists should not be hanged, as it would not serve any purpose. Instead, they should be castrated. The line, ‘I am a rapist’, should also be permanently etched on their foreheads. This is the lesson which should be taught to the Delhi rapists, and many others will never dare to approach a girl with bad intention.”

And while the gulabi doesn’t kill anyone, more violent strains of vigilantism have been reported elsewhere in India among dispossessed women. In 2004, for instance, a mob of hundreds of women hacked to death serial rapist and murderer, Akku Yadav, after the courts failed to convict him over a period of 10 years. After the deed was done, the women collectively declared their guilt in the murder, thereby frustrating police efforts to charge anyone with the crime.

Background

Seeds of rebellion were sown early in Sampat Pal’s mind when her parents refused to send her to school. But despite opposition, the daughter of a shepherd learnt to read and write by watching through the boys’ classroom window, without letting her parents know of it.

Sampat, who, back then, was way ahead of her time, loathed the village society that refused to educate girls, and either married them early or bartered them for money.

“I finally ended up going to school, after I began writing and drawing on the walls of our home,” she said. “My parents had given in very reluctantly, but they hatched another plan and decided to marry me off.”

Sampat eventually became a child bride in a region where child marriages are common. Having her first child at the age of 13, by the time she turned 20, Sampat had five children. But that did not deter her from being on her own.

Her husband had by then known that his wife was an independent-minded woman and encouraged her in her pursuits. She took up a job as a government health worker, and added to the family income. She tried to fight the system, but sensing that her hands were tied due to government’s mechanisms, and that she was unable to work for the welfare of women, Sampat soon became dissatisfied. She quit the job.

“I wanted to work for the people, and began holding meetings. While networking with women, I realised that they were ready to fight for a cause. The issues were many; including child marriages, dowry deaths, farm subsidies and misappropriation of government funds,” the crusader said.

Making her way from one far-flung village to another on an old rusty bicycle, Sampat holds daily gatherings under shady banyan trees, near makeshift tea-stalls selling the sweet Indian drink, chai, and other popular village hangouts to discuss local problems, and attract new recruits.

One village is quoted as saying: “We are poor and illiterate and have no support. We find that, collectively, the women are not afraid of breaking the rules, and defend the weak. They have earned respect in villages far and wide, and the men no more hesitate in approaching them. Many times, Sampat and her group have forced policemen to register complaints against the offenders.”

The Gulabi Gang has thousands of women under its banner. But Sampat refuses to associate with any political party or NGO. “All of them approach us with their own agenda,” she says. “Some educated and affluent people even collect donations in our name, which never reaches us.”

Sampat made it to The Guardian’s list of ‘Top 100 Women: Activists and Campaigners’. Several documentaries have been made on her, and women all over the world appreciate her courage.

“What surprises me,” a puzzled Sampa says, “is the fact that I am admired the most by women in Western countries. So many of them say they got inspired by me, and have begun fighting for their rights at home and workplace after reading about me.”

She has been invited to international forums, and has travelled extensively to such places as the US, France, Sweden and Italy.

For a woman belonging to one of the poorest parts of the most populous State in India, it is reason enough to feel honoured. Banda has long been male-dominated, with domestic violence a common occurrence. But Sampat has changed all that. Men applaud her, and some are now associated with the Gulabi Gang.

The Gulabi gang is the subject of the 2010 movie, Pink Saris, by Kim Longinotto; and the 2012 documentary, Gulabi Gang, by Nishtha Jain. Another movie, Gulab Gang, starring Madhuri Dixit in the lead role, is to be released on International Women’s Day, March 8, 2013.

.jpg)