BELMONDO’S engaging personality on and off-screen is based on what he must have absorbed from cinematic history, and what artistic values he shared in collaboration with particularly French directors like Godard, Truffaut, De Broca, and Resnais.

We can find prior examples of Belmondo’s exuberant, defiant, and innovative personality in ever-fresh Clark Gable classic films like: ‘IT HAPPENNED ONE NIGHT’ (1934) , ‘HONKY-TONK’ (1941), ‘THE HUCKSTERS’ (1946), or ‘THE MISFITS’ (1961). Also John Garfield classics like: ‘DESTINATION TOKYO’ (1943), ‘HUMORESQUE’ (1946), or ‘BODY AND SOUL’ (1947).

We can find prior examples of Belmondo’s exuberant, defiant, and innovative personality in ever-fresh Clark Gable classic films like: ‘IT HAPPENNED ONE NIGHT’ (1934) , ‘HONKY-TONK’ (1941), ‘THE HUCKSTERS’ (1946), or ‘THE MISFITS’ (1961). Also John Garfield classics like: ‘DESTINATION TOKYO’ (1943), ‘HUMORESQUE’ (1946), or ‘BODY AND SOUL’ (1947).

It is obvious that the engaging characterizations we see in these films with Gable and Garfield are far from entirely the desire of their scripts and directors. These film-roles connect with aspects of the actual real personality and ideas of the actors, who are not imposing models of behaviour on audiences, but rather exploring, questioning and criticizing both positive and negative aspects within their roles, their own personality, and the personality of film viewers.

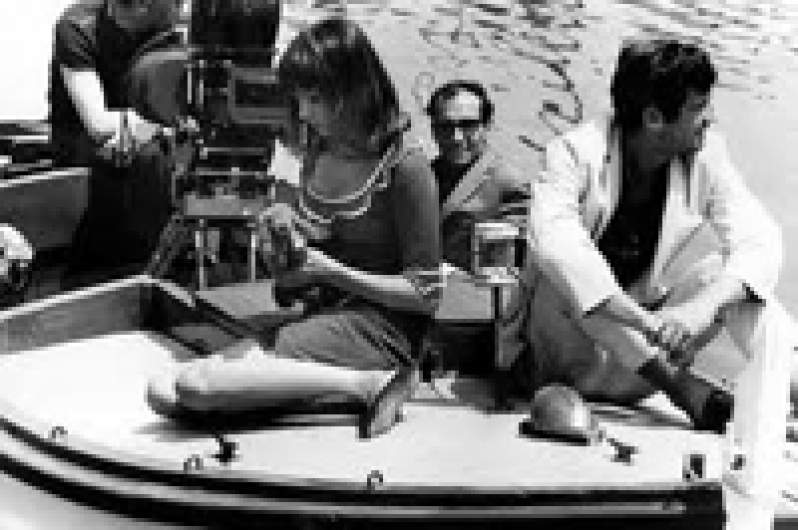

elmondo & GodardIn 1965, Belmondo got together again with Godard to make ‘PIERROT LE FOU’ (‘Pierrot the Crazy’), the second of three films they would make together, with ‘MASCULIN-FEMININ’ being the third and final.

‘Pierrot Le Fou’, one of Godard’s early best, brought Belmondo’s real personality with its concerns about social freedom, literature, art, and a new possibility of movie-making to bear upon the character he is about to play for Godard, since Godard himself had no idea what his film would be about.

James Monaco, in his essential book, ‘THE NEW WAVE’ (1976), quotes Godard as saying about the making of ‘Pierrot Le Fou’:

“It is a completely spontaneous film. I have never been so worried as I was two days before shooting began. I had nothing, nothing at all.” All he had in mind was some filming locations, and that most of the film would occur near the Mediterranean Sea and seacoast, which became a favourite New-Wave location.

Belmondo then, up to the last minute, had no script and no dialogue to memorize. Nothing to work from, except his discussions with Godard and the inventive exuberance of his personality, which was what Godard wanted and needed from him.

Making of a classic What Belmondo and Godard, as the two leading creators of ‘Pierrot Le Fou’, relied on in the making of this film was the advanced cultural knowledge of their personalities. Only artistic personalities filled with knowledge of the history of film, literature, art, music, fashion, politics, history, and diverse geography can make a movie as though from nothing, with little plot or narrative content other than the physical and mental resources of the director and his chief actors/characters, Belmondo and actress Anna Karina, who begin a spontaneous journey together, abandoning the jaded materialism of their Parisian society life and driving out to the Mediterranean seacoast, where, as we know, so many ancient cultural and historical foundations were laid.

What Belmondo and Godard, as the two leading creators of ‘Pierrot Le Fou’, relied on in the making of this film was the advanced cultural knowledge of their personalities. Only artistic personalities filled with knowledge of the history of film, literature, art, music, fashion, politics, history, and diverse geography can make a movie as though from nothing, with little plot or narrative content other than the physical and mental resources of the director and his chief actors/characters, Belmondo and actress Anna Karina, who begin a spontaneous journey together, abandoning the jaded materialism of their Parisian society life and driving out to the Mediterranean seacoast, where, as we know, so many ancient cultural and historical foundations were laid.

Of course, all sorts of risky adventurous moments occur, but the film’s main focus is on what Belmondo and Karina do with their time; what they read, look at, and say to each-other.

Belmondo draws on the reservoir of cultural knowledge within his personality to create his screen-role as the film progresses. Yet, the film itself, reflecting Godard’s cultivated creative personality, is not without traditions started by some of the most avant-garde writing and painting.

Its fragmented cinematic style is really influenced by the form of T.S. Eliot’s eclectic and intellectually exciting epic poem, ‘The Waste Land’; its spatial and temporal ambiance from Proust’s astonishing novel, ‘In Search of Lost Time’; its visual sharpness by Picasso and Matisse’s form and colour; its romanticism by Rimbaud’s poetic pastoral wanderings; and other sensual modern literary sources.

Because of such a style of cultural quotations representing Belmondo and Karina’s modern sensibilities, ‘Pierrot Le Fou’ despite its unorthodox and even shocking form and content, became, up to now, an internationally successful film whose worth is not decided by award competitions, or passing time and trends, since its very topic concerns such subject matter. Its value as art is much more authentic, and became a foundation of the New Wave’s permanence since 1965.

Belmondo’s form

Those who have difficulty with Godard’s, Truffaut’s, Resnais’s, Antonioni’s or Fellini’s films, have either never read or appreciated Eliot’s and Pound’s poems, or failed to recognize their similarity in form to such poetry. Whereas content may be subjected to passing historical events and attitudes, which become platitudinous and weak with time, form may survive if it reflects the inconstancy of time, and the imaginative process. Belmondo himself often personifies such form that remains perennial because of his questioning, un-stereotypical roles. ‘PIERROT LE FOU’ opens with Belmondo in his comfortable home’s bathtub reading to his daughter from a critical study on the baroque Spanish painter Velasquez’s interest in time and space. Even if the child cannot comprehend everything her father is reading to her, his illogical act is a brilliant signifier in support of education. His roles also criticize cultural pursuits contaminated by crime, as in ‘THAT MAN FROM RIO’, where his girlfriend’s uncle, an archaeologist in Brazil, discovers that three ancient tribal Indian artefacts contain clues to a treasure of precious stones, and gradually murders his colleagues to get them. In ‘PIERROT LE FOU’, Belmondo’s interest in comic book heroes and living intensely leads to a feeling of fulfillment, so he decides to end his life dramatically by lighting a coil of dynamite placed around his neck. However at the last minute he decides it’s a silly idea and changes his mind, but now he cannot manage to remove the dynamite in time and explodes with it. The scene is touchingly tragic-comic, and suddenly critical of the film’s entire premise of freedom and spontaneity it started with. Like cinematic diplomats Godard and Belmondo give with one hand and take with another.

The pursuit of such unconventional artistic values via cinema, and other art forms, is welcomed by actors and directors like Belmondo and Godard in modern cultures which encourage and support such quests, and these artists become in turn successful stars at their critical and paradoxical task applauded by their society.

.jpg)