THE legacy of modern visual art’s legacy of influence on New Wave films is also indebted to Matisse’s large and shockingly beautiful paper cutouts, significantly influenced by the modern jazz of Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker and others, whom Matisse liked, calling his first collection of large cutouts ‘JAZZ’, made by ‘improvisations in colour and rhythm’, but also tropical environments like Tahiti and Morocco where Matisse travelled.  Also influential in the long-run are Raoul Dufy’s vivacious French Riviera paintings; Mondrian’s geometric works; the Italian ‘Continuity’ group paintings of Dorazio and Perrili; the Scotsman, Alan Davie’s bright Jazz-inspired abstract paintings; Toronto abstractionist, Jack Bush’s joyful hard-edge paintings; Venezuelan kinetic artists, Soto, Cruz-Diez and Otero’s works; the Brazilian Constructivists such as Lygia Clark, Helio Oitica, Sergio Camargo and Rubem Valentim; also the American monochromatic colour-field abstract painters, Clifford Still, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Sam Francis, Richard Diebenkorn, Frank Stella, and Helen Frankenthaller.

Also influential in the long-run are Raoul Dufy’s vivacious French Riviera paintings; Mondrian’s geometric works; the Italian ‘Continuity’ group paintings of Dorazio and Perrili; the Scotsman, Alan Davie’s bright Jazz-inspired abstract paintings; Toronto abstractionist, Jack Bush’s joyful hard-edge paintings; Venezuelan kinetic artists, Soto, Cruz-Diez and Otero’s works; the Brazilian Constructivists such as Lygia Clark, Helio Oitica, Sergio Camargo and Rubem Valentim; also the American monochromatic colour-field abstract painters, Clifford Still, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Sam Francis, Richard Diebenkorn, Frank Stella, and Helen Frankenthaller.

Style of directors

The New Wave film director finds and uses structural parallels in the world’s environment, natural or man-made, which are creatively suggested by the above formal visual art. A beautiful example is Antonioni’s use of Palladio’s spiral staircase in the Monastery of Santa Maria della Carita of Venice (1560-61) to frame a scene (also used on one of the posters) in his 1982 film, ‘IDENTIFICATION OF A WOMAN’.

So, of course, the inclusion of actual works of visual art can also add enormously to film’s sub-textual or implied signification. But what is the human point of all this in-bred creative inspiration for New Wave films and their audience?

The whole point of such art is to make us aesthetically satisfied and aware of artistic beauty, and self-contented with art that is both humbled by the pleasures of everyday life and inspired by the display of individual and collective love among the characters of such films.

New Wave directors demonstrate and share their love of creative culture, on the whole, by presenting characters who often express love beyond their own cultural and racial backgrounds; and equally important, in contradiction to the negative or catastrophic events that come with life, but remain a fraction of its total reality on a planet that plays no part in episodes of Man’s own bitter and deranged behaviour.

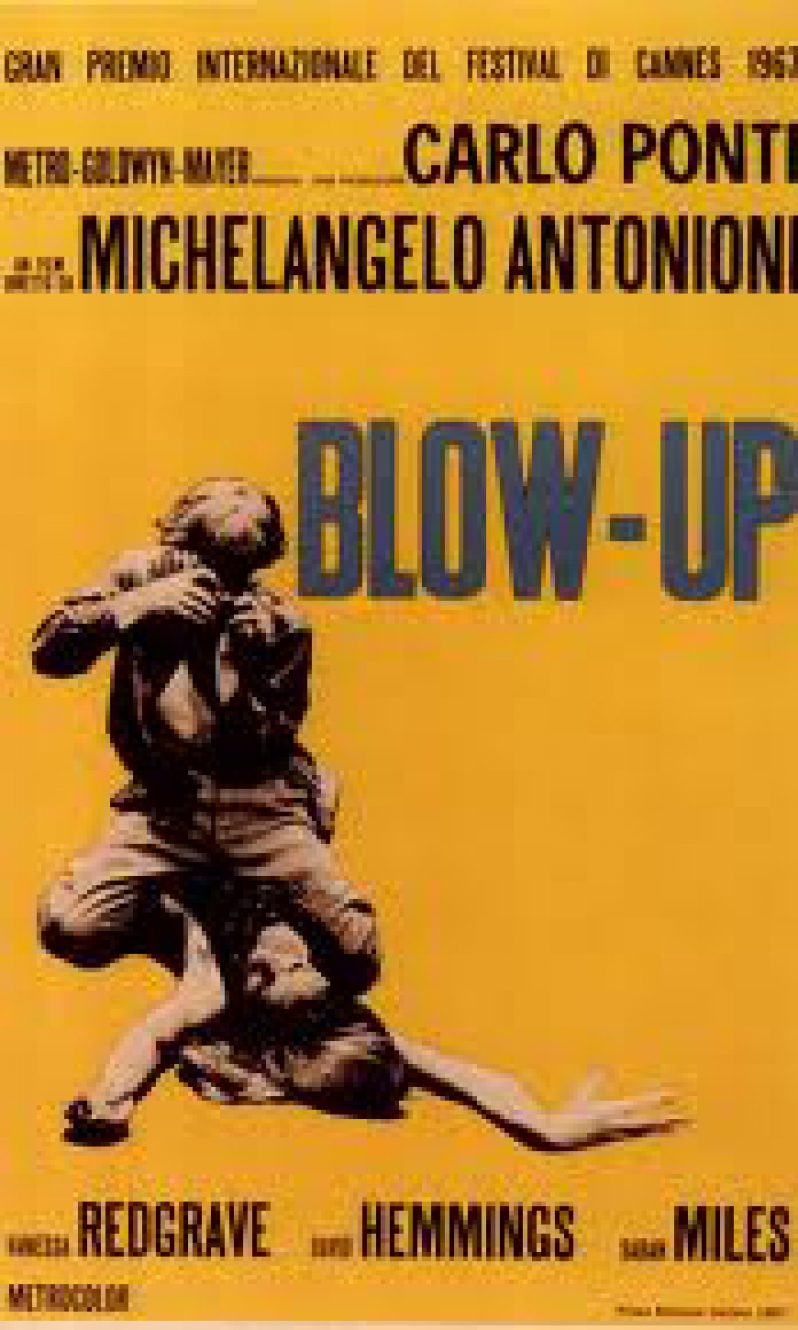

Antonioni’s ‘Blowup’ What makes Antonioni’s New Wave film classic, ‘BLOWUP’ forever exemplary in illustrating and solving social dilemmas, and inspiring other New Wave artists are the implications of many of the film’s scenes. For example, when David Hemmings, as the young London fashion photographer, innocently takes photos of Vanessa Redgrave and an elderly man frolicking in a lonely park, and Redgrave chases after him for the photos, and he tells her to come to his studio, his motivation is strictly for fun, pleasure, relaxation, seduction; he has no idea as yet what she has done, and that she cannot relax because she desperately wants the roll of film, the enlargement or blowup of which can uncover the homicide she was luring the man to.

What makes Antonioni’s New Wave film classic, ‘BLOWUP’ forever exemplary in illustrating and solving social dilemmas, and inspiring other New Wave artists are the implications of many of the film’s scenes. For example, when David Hemmings, as the young London fashion photographer, innocently takes photos of Vanessa Redgrave and an elderly man frolicking in a lonely park, and Redgrave chases after him for the photos, and he tells her to come to his studio, his motivation is strictly for fun, pleasure, relaxation, seduction; he has no idea as yet what she has done, and that she cannot relax because she desperately wants the roll of film, the enlargement or blowup of which can uncover the homicide she was luring the man to.

So we see Hemmings letting her into his studio, inviting her to sit, relax, and have a drink while he puts on the modern jazz album he likes by innovative Afro-American jazzman, Herbie Hancock. This scene shows us the important contrast between two young people: One constructively involved with the pleasures of art; the other mentally distracted and anxious because of the violence and evil she is willfully involved with.

Third World New Wave

The difference of New Wave art, especially film, from most familiar or repetitive types of art is that it does not accept or choose any fatalistic destiny as its topic, but reflects a positive influential role for art in our lives and life on this planet.

The 1960s French Nouvelle Vague cinema out of Paris was followed by equally unique New Wave films from Cinema Nouveau of French Canada, and Cinema Novo of Brazil, among others. But some of the most exciting, original and vibrant recent New Wave films emerged from African territories like Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso and Guinea, also from highly artistic Asian cities like Hong Kong and Mumbai.

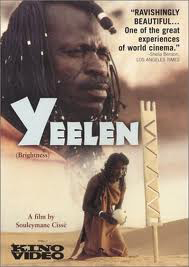

‘YEELEN’, directed by Mali-born Soulemane Cisse in 1987, swiftly rose to become one of the major non-Western New Wave films of the 20th Century by its sheer visual and moral beauty, which rendered the African landscape as the true origin of African identity, rather than routine racial inheritance, and showed this landscape in its powerful role as a cosmic source of life, rooted in planetary elements.

Cisse’s artistic style stunned, because it is rooted in the earth’s original planetary truth, not simply historical or sociological data, and what underlined its beauty is that it was filmed only at dawn, noon, and dusk.

Its true star is an art object: A geometric African sculptural object inserted with a prismatic mineral stone which represents a magical modern work of art with the brightness (Yeelen) of a film projector which destroys regressive sorcery rooted in evil, or obvious inhumane attitudes.

‘Yeelen’ is a classic of New Wave creative elements. Diop Mambety of Senegal, one of the pioneer New Wave directors of Africa, made about eight 45-minute films that are classics of the style, complete with a brilliant balanced use of signifying objects and sites, such as a tenement door (its similarity to an art object is obvious) upon which a wandering musician has pasted his winning lottery ticket, and has to remove and lug it across town and submerge it in the surf of the beach in order to un-pry it in ‘LE FRANC’, before he can claim his winnings.

Mambety’s unique films are the essence of New Wave art’s structure, colour, music, human beauty, sympathy and kindness.

Similarly, the films of Hong Kong’s young New Wave film directors, like Wayne Wang and Wong Kar-wai, also China’s Zheng Dongthian, have to be seen to confirm that films can achieve and convey such soothing creative values of visual pleasure: Sizzling monochromatic surfaces, patterns of silk on the female body, oriental steps, banisters, hallways, food, fashion etc. fill the screen with magical artistry (rather than fantasy, special effects and noisy camera tricks) in Kar-wai’s 1990s New Wave films like ‘DAYS OF BEING WILD’ and ‘IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE’.

These are some of the reasons why New Wave art and films, like its music and literature, are an essential part of the exciting educational lives of those beautiful people of the world today concerned with constructive pleasures.

.jpg)