WHEN numerous readers, whether professionals or lay persons, express exasperation upon encountering contemporary writing which assumes the visual characteristics of paintings or films, via descriptive language, they are denying the aesthetic influence of both antique and later modern literature which reveal a progression based on a firm tradition in the arts.

The same relationship applies to the contemporary use of memory, dreamscape, magical transformations, travel, and baroque or effulgent language, which is also rooted in certain works by Baudelaire, Huysmans, Flaubert, Nerval, Gautier, Walt Whitman, Proust, Joyce, Woolf, or Faulkner.

UPKEEPING AESTHETIC LANGUAGE

If creative literature today is to exchange the detailed and complex richness of ancient and early progressive modernist texts by such writers mentioned above, for any ‘trendy’ objective of mainly a staid and easy clarity of simple rapid storytelling, then creative writing can largely descend into a state of forgettable and ineffective verbal mediocrity.

But apart from the writing and reading habits of both writers and readers who help make such a decline, the denial or ignorance of how the tradition of complex, yet exciting, or interesting literature has actually influenced many popular best-selling books of today, seems to go unrecognised.

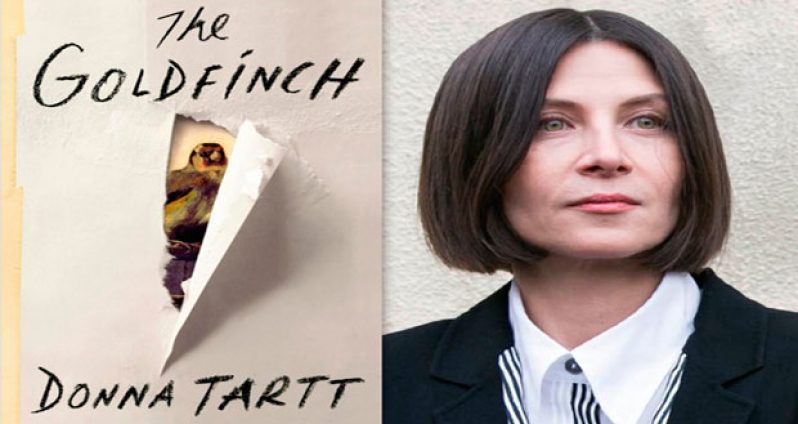

DONNA TARTT’S ‘THE GOLDFINCH’

A good example is the current lengthy reigning bestselling and Pulitzer Prize novel, ‘The Goldfinch’ by young American writer Donna Tartt. Most accolades on this novel keep comparing its style to Charles Dickens’, simply because this novel’s story, told by Theo, a thirteen-year-old High School boy orphaned by a terrorist bomb in a New York art museum which killed his single-parent mother, easily harks back to Dickens’ narrative content obsession with orphans in novels like, ‘Oliver Twist’, ‘Hard Times’, ‘Bleak House’, etc. However, Tartt’s ‘The Goldfinch’ on a stylistic level (which IS really its content!) shows the diluted, yet skillful descriptive influence of much later avant-garde writing, partly by Proust, and Robbe-Grillet, Claude Simon, and even Philippe Sollers, all of the Nouveau Romans or New Novels, with their detailed descriptive emphasis on objects, paintings, architecture, dreams, disturbed states of mind, memories, which Tartt’s hero, Theo, shares. Tartt’s strategy is to stretch and distribute these qualities along her novel’s seven hundred odd pages, so that even if experienced critical readers acquainted with the Nouveau Roman wanted to sum up her book, they could lose this evidence in its lengthy narrative/story as sole content.

CONCISE STANDARDS

A decline in aesthetic value is obstructed when we concentrate on shorter, more linguistically compact or concise writing in which similar emotional stories may be shared. Tartt’s young character Theo is not unique among other more or less one parent orphans in novels of recent decades, such as Claude Simon’s ‘The Acacia’ and ‘The Trolley’, or Cormac McCarthy’s ‘The Road’, among others probably. But these novels are far shorter than Tartt’s by hundreds of pages, and their writing is far more vivid, visually mobile, and emotionally charged, since they do not have the excuse of being written by a child’s first person narrative voice.

Actually, Theo’s narrative voice seems extremely experienced and sophisticated for his age! However, ‘The Goldfinch’, with its admirable combination of lengthy content and focused style, holds up one end of literary quality as surprising proof that such quality writing can nevertheless be sustained today with classic skill.

UNIFIED PLEASURE

What is the bottom line literary value, and real everyday human value, in this search (and upkeep) for a creative literature of quality? Since a decline in the arts seems more and more the result of an inability to create art forms of pleasure which are not compromised or contaminated by other interests, such as social, political, historical, or ethnic obsessions which can be dealt with in the distinct category of polemical writing.

We keep referring to the antique literary works of Homer, Virgil, Petronius, and Apuleius, because they established the priority of style as content, or form as content, as a unified pleasure. Later creative writing, like Flaubert’s ‘Salambo’; Stendhal’s ‘The Charterhouse of Parma’; Huysman’s ‘Against Nature’; Gautier’s ‘Mademoiselle De Maupin’; Fielding’s ‘Tom Jones’; Goncharov’s ‘Oblomov’; Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass’; Proust’s ‘A La Recherché du Temps Perdu’; Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’; Lawrence Durrell’s ‘The Alexandrian Quartet’; Jose Lezema Lima’s ‘Paradisio’….. all established the pleasure of creative writing as a standard of learning which prevents the decline of literature as art. It is Barthes again who would clarify this value in ‘The Pleasure of the Text’, when he wrote: “What if knowledge itself is delicious? Pleasure….is not a naïve residue; it does not depend on a logic of understanding and on sensation; it is a drift, something both revolutionary and asocial, and it cannot be taken over by any collectivity, any mentality, any idiolect….It is obvious that the pleasure of the text is scandalous: not because it is immoral but because it is a topic.”

By Terence Roberts

.png)