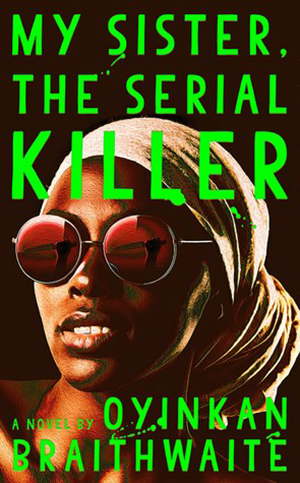

OYINKAN Braithwaite’s novel, ‘My Sister, the Serial Killer,’ brought to mind Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s famous Ted Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” for two reasons. The first is that Adichie is Nigerian and the novel, set in Lagos, is written by another writer from the same country. The second reason has to do with the fact that Adichie’s Talk forces us to contemplate the multifaceted nature of identity, and how we are each not one thing only.

This is broadened to encapsulate the arts, particularly with regard to what the duty of an artistic creator actually is, and how the expectations of readers and audience members can be shaped. Braithwaite’s novel, set in Nigeria, with Nigerian characters, and by a Nigerian author, does not concern itself with the stereotypical concerns that much of the reading public has been conditioned to expect from works by authors who live in Africa. ‘

This is broadened to encapsulate the arts, particularly with regard to what the duty of an artistic creator actually is, and how the expectations of readers and audience members can be shaped. Braithwaite’s novel, set in Nigeria, with Nigerian characters, and by a Nigerian author, does not concern itself with the stereotypical concerns that much of the reading public has been conditioned to expect from works by authors who live in Africa. ‘

My Sister, the Serial Killer’ is not about race or war, nor does it concern itself with religion or post-colonialism. The novel is an old-fashioned thriller set in a modern world, with themes that resonate in the modern – such gender roles, the concepts of beauty and femininity, sibling relationships and rivalry, and the dynamics of power. Braithwaite’s novel is unique in that although it deals with murder, abuse, and other topical issues, it still manages to imbue the story with dark humour, comedy that transforms the narrative into a biting satire, particularly with regard to men and their haplessness in the face of conventional beauty.

The plot of the novel revolves around two sisters, Korede, the elder, intelligent, focused one who works as a nurse, and her staggeringly beautiful younger sister, Ayoola, who is a fashion designer by trade, but by the beginning of the novel has already brutally murdered three men.

Korede realises that her sister is a serial killer, as she claimed her third victim and maybe on the prowl for more.

However, where another writer may have tried to pit the sisters against each other in some sort of cat-and-mouse game, Braithwaite chooses to go another route, making Korede complicit in the crimes of her sister, as it is Korede who uses her medical knowledge to get rid of traces of blood after Ayoola’s murders. Korede tells her sister how to get rid of the body; Korede tells her what lies to say.

The bond between the two is so strong that Korede, although she knows her sister is a psychopath, still has to maintain her duty as an elder sister by protecting Ayoola at all costs and ensuring that no harm comes to her. Of course, things take a dark turn when Ayoola next sets her eyes on Tade, the handsome doctor with whom Korede is in love.

‘My Sister, the Serial Killer’ thrives particularly due to the characterisation of the two central figures in the text. The siblings are the exact opposite of each other, and this not only builds tension in the story; it also helps to promote the writer’s wicked sense of humour. Ayoola, despite being a killer, has always liked for things to come to her easily.

Men, gifts, money – she has never had to try really hard before and, therefore, she relies on the more grounded Korede for support after the murders when quick-thinking, tact, and restraint are needed. Ayoola’s near-disastrous mistakes and her spoiled, pouty ways, such as yearning to return to social media instead of spending an appropriate time away ‘grieving’ for the ex-boyfriend who has gone ‘missing,’ or the scene in which she grudgingly comforts the relative of a man she has killed, for example, make her one of the most unique serial killers in all of literature. She is reminiscent of ‘cool girl’ Amy Dunne from Gillian Flynn’s ‘Gone Girl,’ but Ayoola is more optimistic. She is the manic pixie dream girl version of a serial killer.

Similarly, Korede is a particularly unique heroine, in that, up to a point, she has knowledge of her sister’s murders and assists her in getting rid of the bodies and all other evidence. Far from worrying about the character’s inability to ‘do the right thing,’ however, Braithwaite uses this to emphasise the deep love, trust, and protective instinct that the sisters have for each other. The novel comes to us from Korede’s perspective, and the text is written in such short bursts with Korede as such a compelling character that you just keep reading on and on, hooked to her story in much the same way men get hooked to her sister.

Braithwaite’s ability to both write and interweave humour to create a satirical, serial killer novel is extremely admirable. Her humour is big, like the stab of a knife or a punch in the gut. For example, in an early scene Braithwaite captures the humour, as well as Korede’s love for the doctor, Tade, her desire for acceptance, and the fact that she is the exact opposite of her sister, in one short scene when we are given Korede’s poor attempt at seduction:

As I exit the room, I swing my hips the way Ayoola is fond of doing.

“Are you okay?” he calls after me… I turn to face him.

“Hmmm?”

“You are walking funny.”

“Oh, uh – I pulled a muscle.” Shame, I know thy name.

“My Sister, the Serial Killer” was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and I think that it definitely deserved the honour as it is, from my perspective, an important piece of African literature. Here we have a Nigerian story, an African story that does not play into the stereotypes.

It is about a serial killer – and that is okay because Nigerian literature and African literature is more than just being about the things we know they are about. In this novel, we have a story about a different side of Nigeria. With this novel, we are given a story that continues to break the mould of African literature that has been formed on stories built with stereotypes, and for that, I am grateful.

.png)