-

from history rather than agenda

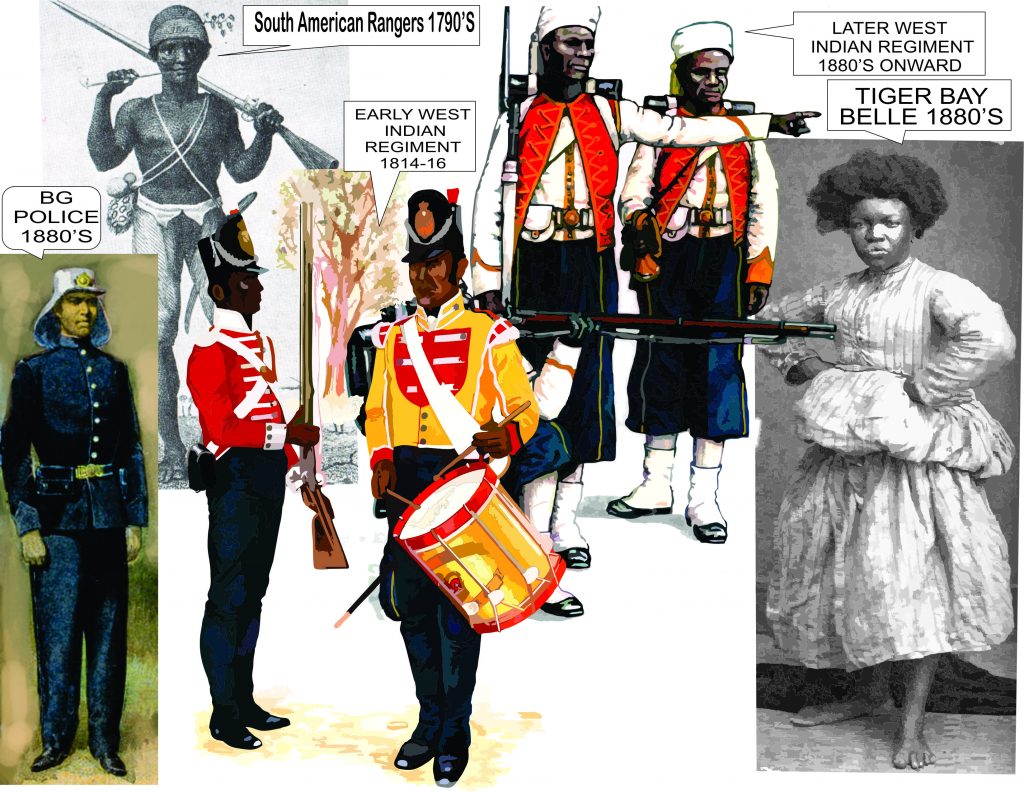

THERE was no separate police force in the ancient world. Policing was done by the army and their departments, mostly by those regiments designated for the in-house protection of borders, towns and cities. In colonial British Guiana, the first decision to create an Afro-colonial group was in 1796, the Rangers. This decision was made after the 1795 Maroon war between the Stabroek colonial forces and the feared Maroons of Boerasirie.

The Stabroek forces were defeated and they retreated. Major McCreagh recognised that the white militia had no interest in engaging the Maroons in a bush fight and were more inclined to conduct a treaty, resorted to recruiting some 400 slaves (most likely new to the colony) who would gain their freedom through military service. They were referred to as ‘The Demerara South American Rangers,’ but possibly only 100 of them were trained, when, through urgency, with the help of the Amerindians (Caribs) these troops were immediately committed to engaging the Maroons, Emancipation magazine #3 1995. This was the first deployment of the non-white population of Stabroek under British administration deployed as a military body. But they would not be the last.

According to the British Military historian Sir Fortescue, the British army was severely depleted in the Haitian expedition-see Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James. The West-India Regiments of the English Afro-Caribbean were incorporated as early as 1798 to sustain British military needs; they were deployed in the 1823 Demerara insurrection, the regiments here at that time were from other Caribbean colonies, mainly Barbadian, the West Indian Regiment were also a part of WWI for further reading of its, at times turbulent history, see-The Empty Sleeve by Brian Dyde. The concept of an organisation-trained institution to maintain civilian adherence to the law was born in England. The police force came into being, following Sir Robert Peel’s Police Bill in the early 1830s, and like their counterparts in the colonies much later, constables were unarmed, except for a baton and whistle. The first semblance of a police force in British Guiana was drawn from the trained South American Rangers who joined the force in the mid-1800s were ex-soldiers and hailed from Berbice. Quote; “ By 1819 the police establishment of Demerara and Essequibo consisted of the First and second Fiscals, a drossart, a cipier and seven dieneers; then in 1821, 12 night guards existed. In 1825 a separate category of ‘nightly watchmen’ was employed. The establishment of Demerara and Essequibo comprised seven dienaars and 12 night guards under the command of each Fiscal, while in Georgetown the establishment was 18 night watchmen for the business section; nine being on duty every alternate night. One dienaar was attached to the jail, two to the Fiscal’s office, two were in constant readiness for orders, and one attended Court of Justice and Court of Policy.” See-History of Policing in Guyana by John Campbell, B.A [ Dieneers-servants, Fiscal- financial official].

According to the British Military historian Sir Fortescue, the British army was severely depleted in the Haitian expedition-see Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James. The West-India Regiments of the English Afro-Caribbean were incorporated as early as 1798 to sustain British military needs; they were deployed in the 1823 Demerara insurrection, the regiments here at that time were from other Caribbean colonies, mainly Barbadian, the West Indian Regiment were also a part of WWI for further reading of its, at times turbulent history, see-The Empty Sleeve by Brian Dyde. The concept of an organisation-trained institution to maintain civilian adherence to the law was born in England. The police force came into being, following Sir Robert Peel’s Police Bill in the early 1830s, and like their counterparts in the colonies much later, constables were unarmed, except for a baton and whistle. The first semblance of a police force in British Guiana was drawn from the trained South American Rangers who joined the force in the mid-1800s were ex-soldiers and hailed from Berbice. Quote; “ By 1819 the police establishment of Demerara and Essequibo consisted of the First and second Fiscals, a drossart, a cipier and seven dieneers; then in 1821, 12 night guards existed. In 1825 a separate category of ‘nightly watchmen’ was employed. The establishment of Demerara and Essequibo comprised seven dienaars and 12 night guards under the command of each Fiscal, while in Georgetown the establishment was 18 night watchmen for the business section; nine being on duty every alternate night. One dienaar was attached to the jail, two to the Fiscal’s office, two were in constant readiness for orders, and one attended Court of Justice and Court of Policy.” See-History of Policing in Guyana by John Campbell, B.A [ Dieneers-servants, Fiscal- financial official].

Damon of La Belle Alliance was the last enslaved African to conduct a peaceful protest against the plantocracy against the four years of apprenticeship. Damon was executed by Governor Carmichael Smyth for protesting and raising symbolic flags of independence in the yard of the Public Buildings post-emancipation 1834, and severe punishments were carried out against his brethren. Post-emancipation British Guiana was by no means a place of social calm. The colony was plagued by joblessness, low wages, clustered living and unhygienic impositions. These conditions as a consequence led to the necessity for an extended lunatic asylum, a Leprosy Asylum and a Tuberculosis Hospital. Crime was an issue among the unemployed; this is how the definition of Centipede for groups of the urban population emerged to describe a frustrated, stressed, streetwise and physically tough attitude type; George Street was even called Centipede Alley. Post-emancipation permitted the swift inclusion of Africans (apprentices) into the early police force, as breaking and entering on the waterfront had become a problem.

There is a popular photograph of a young woman said to be a mid-1800s ‘Tiger Bay’ resident, with a caption from that time that states, “She was remembered by a former Sheriff of Demerara as a match for any three policemen and…a terror to the neighbourhood.” This extraordinary portrait was displayed at a local exhibition in 1879. I have known women like this in the 70s: Norma Sargeant, Yvonne, Corn Hero, Annabelle, among others. Thus, the policeman of the 19th century in the maintenance of law and order had to be a physically imposing and capable person; yet there are records of policemen stabbed by resisting lawbreakers and killed and injured by protestors during that period, and there were constant protests.

It is amazing that with the availability of existing records of that period that any , in this case, the current ‘Guyana Times’ and a post by my colleague Malcolm Harripaul on social media have alleged racial marginalisation of East Indians on the grounds of race by both the colonial and post-independence authorities in the early and later police force recruitment procedures. Those articles are not rooted on efforts of research and cross-research, and thus this article, though constructed within limited space, but with source material references, was necessary to be written.

Quote- “In 1885, quite a number of East Indians joined the force. Out of 157 ranks enlisted that year, 58 were East Indians, several of them were recommended by the immigration Agent- General or Sub-Agent. Many of those were recorded among the 133 illiterates shown in Table 1. [which also includes other ethnic groups, including European; my inclusion] But not all Indians recruited during this period were illiterate, for some of them including PC 338 Khewajbush a Calcutta labourer and 331 Bhagwant, a Brahmin could have read and written. It also appeared that some of the illiterates learned to read and write while in the force, and a few pretended not to know how to do so on enlistment: among such cases on record was that of PC 483 Kallo, who was recorded as being illiterate on joining in 1884, but who was in 1887 found guilty of a breach of discipline by writing directly to the Inspector-General. Several of the illiterate Indians withdrew at their own request, but many rallied. A remarkable case was that of PC 462 Hackim, an illiterate labourer from Calcutta. He joined the force in 1888 as a third- class constable, was promoted second class in 1892, first class on probation in 1894, unpaid L/Cpl. 1896, Cpl. 1898, Lance Sergeant on probation 1899, Sergeant in 1900, Lance Sergeant Major on probation in 1902 and Sergeant Major in 1903 at the age of 42.” The History of Policing in Guyana by John Campbell, B. A, no attempt at any document directed at the history of the joint services in any area could be understood and honestly presented without the task of clearing a path through the time pockets of both the uniformed and social period records. We owe the efforts and special innate skills of Policeman/Anthropologist John Campbell for his contribution to the national pool of knowledge on behalf of the police force.

In closing, I wish to summarise the May 18, 1885 address by Inspector-General Cox to indentured recruits, (from the same text) he insisted on the ability to understand English, or not be in the police force, must be willing to arrest members of one’s own race, must keep away from having your own way with opium, ganja and tobacco, and he insisted that “Police duty and rum cannot go together.” For any honest analyst of this subject and its varied angles, John Campbell’s contribution is inescapable, and I must emphasise the need for the creation of the much needed Heritage Commission in the near future.

.png)